21 May 2014 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

.jpg) Presently there is a substantial discourse on whether the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka is waning in its commitment to the institutions of democracy. This insight explores a different question, is it waning its commitments to social institutions?

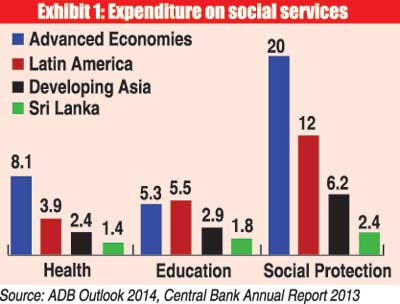

Presently there is a substantial discourse on whether the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka is waning in its commitment to the institutions of democracy. This insight explores a different question, is it waning its commitments to social institutions? Expenditure is not only low, it has been declining during the better part of the last decade (since 2006, Exhibit 2). The expenditure on education, health and community services as a percentage of GDP has been in steady decline and approaching record lows. This trend suggests that Sri Lanka’s commitments to its social institutions are waning.

Expenditure is not only low, it has been declining during the better part of the last decade (since 2006, Exhibit 2). The expenditure on education, health and community services as a percentage of GDP has been in steady decline and approaching record lows. This trend suggests that Sri Lanka’s commitments to its social institutions are waning.

25 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 5 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 6 hours ago