26 Jun 2013 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Sri Lankan economy is reported to have grown by 6.4 percent in 2012. This was less than what was hoped, but still a robust level of growth. In 2010 and 2011 growth was an extremely healthy 8 percent and 8.2 percent. The puzzle is that the growth in the economy is not being reflected in the jobs; this is true when tracking growth ever since 2005. A closer look is needed at this puzzling phenomenon of jobless growth.

The Sri Lankan economy is reported to have grown by 6.4 percent in 2012. This was less than what was hoped, but still a robust level of growth. In 2010 and 2011 growth was an extremely healthy 8 percent and 8.2 percent. The puzzle is that the growth in the economy is not being reflected in the jobs; this is true when tracking growth ever since 2005. A closer look is needed at this puzzling phenomenon of jobless growth.

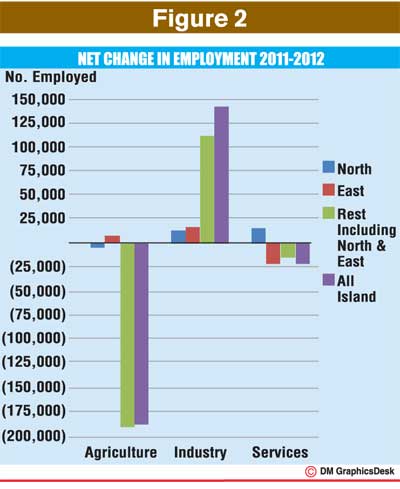

The Northern Province sees a decrease of 4,590 agriculture jobs and an increase of 15,702 jobs in services. The Eastern Province sees an increase of 7,370 agriculture jobs and a decrease of 21,693 jobs in services. Post conflict areas are, as a percentage of their existing jobs, making larger improvements or smaller decreases than the rest of the Island; but are reflecting the same basic problem where job creation is at odds with reported growth.

The Northern Province sees a decrease of 4,590 agriculture jobs and an increase of 15,702 jobs in services. The Eastern Province sees an increase of 7,370 agriculture jobs and a decrease of 21,693 jobs in services. Post conflict areas are, as a percentage of their existing jobs, making larger improvements or smaller decreases than the rest of the Island; but are reflecting the same basic problem where job creation is at odds with reported growth.

26 Nov 2024 31 minute ago

26 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

26 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

26 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

26 Nov 2024 3 hours ago