13 Aug 2013 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

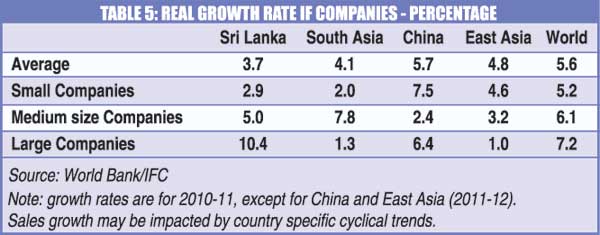

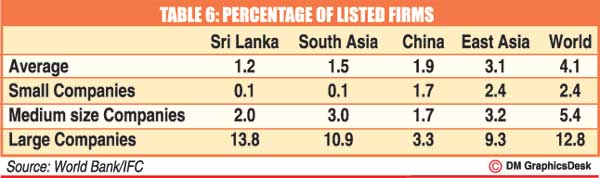

.jpg) Sri Lankan enterprises – especially SMEs use a comparatively high level of bank borrowings to fund investments. This is partly due to low level of domestic savings and inefficiency in the capital market.

Sri Lankan enterprises – especially SMEs use a comparatively high level of bank borrowings to fund investments. This is partly due to low level of domestic savings and inefficiency in the capital market. .jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

26 Nov 2024 8 minute ago

26 Nov 2024 58 minute ago

26 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

26 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

26 Nov 2024 2 hours ago