01 Sep 2023 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Among the great challenges posed to democracy today is the use of technology, data and automated systems in ways that threaten the rights of the public. Unchecked social media data collection has been used to threaten people’s opportunities, undermine their privacy or pervasively track their activity—often without their knowledge or consent. These outcomes are deeply harmful—but they are not inevitable.

These tools now drive important decisions across all sectors fuelled by the power of innovation; these tools hold the potential to redefine every part of our society and make life better for everyone.

These tools now drive important decisions across all sectors fuelled by the power of innovation; these tools hold the potential to redefine every part of our society and make life better for everyone.

The upheaval of artificial intelligence (AI) and its issues that have to be tackled have been defined to five different areas: safe and effective systems, algorithmic discrimination protections, data privacy, notice and explanation human alternatives, consideration and fallback. When you look at the copyright branch of intellectual property, it falls across all these areas in one way or the other.

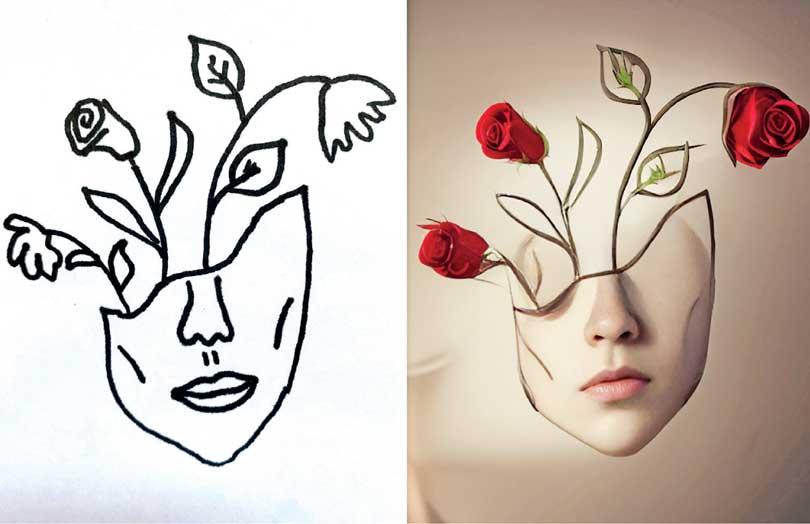

An enormous amount of social media posts, images and articles are being generated daily using AI tools such as ChatGPT, Stable Diffusion and Dall-E, etc. But the crying question is who, if anyone does, owns the copyright in the outputs of these tools and do the tools themselves infringe copyright?

Copyright law

AI tools raise two key questions with re copyright law: one, are the outputs from AI tools protected by copyright at all and if so, who owns those outputs? This determines whether a user can prevent others from copying their AI-created content. Two, do the tools themselves infringe copyright in the underlying materials used to train the tools and can the owners of copyright in those materials prevent the use and exploitation of the AI tools themselves and the outputs of AI tools?

In Intellectual Property Act No 36 of 2003, under the section dealing with copyright, Chapter 1 Section 5, although it does not directly define copyright, states “author” means the physical person who has created the work. “Work” means any literary, artistic or scientific work referred to in the section. Section 6 states that works shall be protected as literary, artistic or scientific work (hereinafter referred to as “works”), which are original intellectual creations in the literary, artistic and scientific domain. Thereafter, it lists down the types of creation.

Hence, when these sections are read together, it is clear that author, which means a person who creates the work, has to be a physical person. This is because as far as legal recognition is concerned, the root of original intellectual creations or originator rests upon a physical person.

In the US, the Copyright Act provides copyright protection to “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device.” 17 U.S.C. § 102(a). The “fixing” of the work in the tangible medium must be done “by or under the authority of the author”. Id. § 101.

In order to be eligible for copyright, then, a work must have an “author”. The human authorship requirement has also been consistently recognised by the U.S. Supreme Court when called upon to interpret the copyright law. In Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, the court’s recognition of the copyrightability of a photograph rested on the fact that the human creator, not the camera, conceived of and designed the image and then used the camera to capture the image demonstrates that human authorship is mandatory. The intellectual invention and given “the nature of authorship”, was deemed “an original work of art … of which [the photographer] is the author.”

Similarly, in Mazer v. Stein, the court delineated a prerequisite for copyrightability to be that a work “must be original, that is, the author’s tangible expression of his ideas”. Goldstein v. California too defines “author” as “an ‘originator’, ‘he to whom anything owes its origin’”. In all these cases, authorship centres on acts of human creativity. Accordingly, the US courts have uniformly declined to recognise copyright in works created absent any human involvement.

UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 clearly stipulates that copyright does not subsist in a work, unless the qualification requirements are satisfied. As regards—(a) the author or (b) the country in which the work was first published or (c) in the case of a broadcast the country from which the broadcast was made. A work qualifies for copyright protection, if the author was at the material time a qualifying person, that “a British citizen, British Dependent Territories citizen, a British National (Overseas), a British Overseas citizen, a British subject or a British protected person, etc”.

In gist, copyright subsists to the expressed idea and it’s owned by the author, who is a physical person or human or who expressed it.

Given this backdrop, many eyebrows will go up at the behest of how and where the copyright will rest. For example, is in the famous ChatGPTs generated content? In this, to generate an output, constitutes the “undertaking” of “arrangements necessary for the creation of the work”. Here what is assumed currently is that the user of the tool and not the producer of the tool would be the first owner of the copyright. Any remaining doubt about ownership as between the user and creator of the tool is attempted to be resolved by contract. The user terms of ChatGPT, assign copyright in the outputs to the user, although the software licence is silent regarding the ownership of outputs.

So, the question that is raised is do AI tools infringe copyright in the underlying materials? Regardless of whether users acquire any copyright of their own in the outputs of AI tools, the providers of the tools and in some cases the users of the tools could be liable for infringing third parties’ copyright in the underlying training materials, depending on the specific implementation of the AI model and process.

Getty Images v. Stability AI

An ongoing litigation in AI that might shape part of the landscape of AI v. copyright is Getty Images v. Stability AI. Here Getty Images is a company that acquires stock footage and sells to subscribers. Getty’s complaint hinges on two primary factors: copyright infringement that is, Stability AI scraping copyrighted images from its database to train its machines without Getty’s consent or compensation and trademark dilution, when the art generator created certain images with Getty’s watermark on them, though distorted—or “bizarre and grotesque”—thus tarnishing its reputation.

However, Stability AI believes that the way in which generative AI technology transforms the material it uses protects it from these claims of misuse. They believe that generative AI technology is protected by the “fair use” doctrine. Fair use of copyrighted material, under the US (as well as Sri Lankan and other countries’ laws) law, protects creators who make use of other people’s material if it is “transformative”, generally understood to mean, if it changes the nature of that material in some way. The scope of ‘fair use’ defences varies significantly between jurisdictions. In general, where the AI tool is used commercially or where it competes with or affects the economic interests of the copyright owner, the chances of falling within an applicable fair use defence are reduced.

It has to be born in mind that an AI-generated image output from the model may not reproduce any part of any single image from a raining set, let alone a substantial part, which is required for infringement under copyright law. But, where the AI output image is made from a small dataset or bears a close resemblance to a small number of identifiable images within the training set, a copyright infringement is more likely. The case is still on.

However, while Getty Images v. Stability AI keeps deliberating a landmark decision, recently decided on a cofactor that can perhaps change the landscape on the issue of copyright and AI. The case presented the question of whether a work generated autonomously by a computer system is eligible for copyright. In the case Stephan Thaler v. Shira Perlmutter Register of Copyrights and Director of the United States Copyright Office, et al plaintiff Stephen Thaler owns a computer system he calls the “Creativity Machine”, which he claims generated a piece of visual art of its own accord. He sought to register the work for a copyright, listing the computer system as the author and explaining that the copyright should transfer to him as the owner of the machine.

The Copyright Office denied the application on the grounds that the work lacked human authorship, a prerequisite for a valid copyright to issue, in the view of the Register of Copyrights. The plaintiff challenged that denial, culminating in this lawsuit against the United States Copyright Office and Shira Perlmutter, in her official capacity as the Register of Copyrights and Director of the United States Copyright Office (“defendants”).

Both parties have moved for summary judgment, which motions present the sole issue of whether a work generated entirely by an artificial system absent human involvement should be eligible for copyright? Judge Howell said “no” and made this critical point about copyright protection and new technologies, including generative AI: defendants are correct that human authorship is an essential part of a valid copyright claim “Copyright is designed to adapt with the times.

Underlying that adaptability, however, has been a consistent understanding that human creativity is the sine qua non (meaning something absolutely indispensable or essential) at the core of copyrightability, even as that human creativity is channelled through new tools or into new media.” Elsewhere in the judgement she held, “Copyright has never stretched so far, however, as to protect works generated by new forms of technology operating absent any guiding human hand, as plaintiff urges here. Human authorship is a bedrock requirement of copyright.”

One issue should not be disputed – copyright protects human creativity. This ruling, which is highly unlikely to be overturned, protects us all.

However, it is obvious that there is no doubt that we are fast approaching new frontiers in copyright law as increasingly artists or any creator for that matter use AI as their toolbox to be used to generate new visual and other artistic works. But the fast-dwindling necessity for an increased attention and focus on human creativity from the actual generation of the final work is going to raise extremely challenging questions.

The two pivotal questions would be: one, where do we draw the line i.e., how much human input is necessary to qualify the user of an AI system to be an “author” of a generated work? And two, how to assess the originality of AI-generated work where the systems may have been trained on unknown pre-existing works and in both these scenarios how copyright law might best be used as an incentive to creative works involving AI as much as protecting the originality and author.

(Chanakya Jayadeva is an Attorney-at-Law on Entertainment Law and New Media Law)

25 Dec 2024 21 minute ago

25 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

25 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

25 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

25 Dec 2024 3 hours ago