I am drawn toward these themes because they’ve often generated ways to illuminate how we see of ourselves in relation to one another. As long as the rights and the terms by which national belonging is contested, not just in Britain but elsewhere, I think it’s worth writing about.

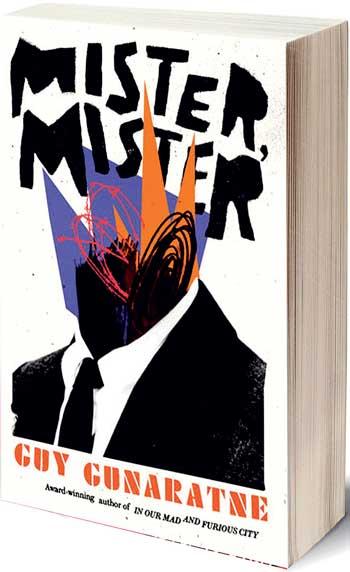

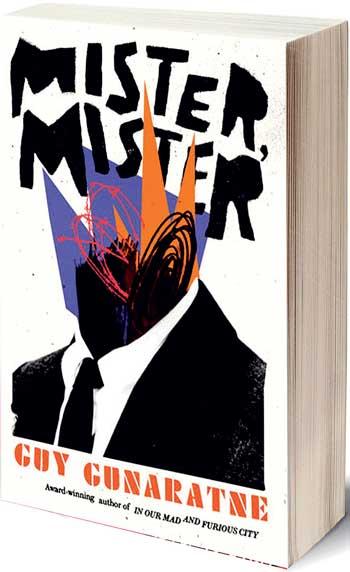

British journalist, novelist and playwright, Guy Gunaratne’s debut novel In Our Mad and Furious City was the recipient of multiple literary awards (International Dylan Thomas Prize, the Jhalak Prize in the UK and the Authors Club Award) and was shortlisted for the Goldsmiths Prize and longlisted for the Booker Prize as well as the Orwell Prize for Political Fiction. Their new book Mister, Mister (2023) is a picaresque tale of a young poet named Yahya Bas who explores his identity and belonging while detained in the UK. At GLF 2024, Guy will discuss the book with Devana Senanayake and also join a panel with Yudhanjaya Wijeratne and Nayomi Munaweera on Radical Fiction.

British journalist, novelist and playwright, Guy Gunaratne’s debut novel In Our Mad and Furious City was the recipient of multiple literary awards (International Dylan Thomas Prize, the Jhalak Prize in the UK and the Authors Club Award) and was shortlisted for the Goldsmiths Prize and longlisted for the Booker Prize as well as the Orwell Prize for Political Fiction. Their new book Mister, Mister (2023) is a picaresque tale of a young poet named Yahya Bas who explores his identity and belonging while detained in the UK. At GLF 2024, Guy will discuss the book with Devana Senanayake and also join a panel with Yudhanjaya Wijeratne and Nayomi Munaweera on Radical Fiction.

Q: Tell us a little about your journey to becoming a writer?

I’ve been writing since I was very young. I knew I wanted to tell stories and live a life entirely dedicated to art and in pursuit of works that can have some effect in the world. I think I understood this as a small boy. It felt as if I was singularly moved by books, film, music in ways other people just were not. And it was, at times, terribly lonely being the only one who didn’t simply want a good job and a salary when I grew up. I knew nobody in the arts. None of my family or friends had any such aspirations. So there couldn’t have been a plan, even if I’d wanted one. I had nobody to ask a favour. I had bags of conviction, however, and thanks to my mother, who made it permissible to believe that I might be the exception but only if I worked hard. A person either has to own who they are or not, I think.

Q: Not many writers can say that their debut novel was a hit from the start, yet your debut novel In Our Mad and Furious City was the recipient of multiple literary awards and was also longlisted for The Booker Prize. What was it like to write and publish your very first novel?

I remember those writing years very well – 5am mornings, a cup of coffee in a blue mug, writing in between reading, all before my day job. It felt like being driven onward by something. Once it was published, the experience was transformative in so many ways, and I’m grateful for the people around me at the time.

Q: You just released your most recent work, Mister, Mister in May 2023 – what’s the premise of the story and what inspired you to write it?

It follows a young poet named Yahya Bas, who at the beginning of the story is found detained in the UK. He is being interrogated by someone he refers to as ‘Mister’. It transpires that Yahya Bas has returned to the UK having travelled to Syria under suspicious circumstances. His poetry is being investigated as having incited violence, and so he begins to tell his life story which stretches from London to Syria and back again. I was inspired by having grown up in the West over the last 25 years and being bombarded by images of young men of a certain class, religion and racial ethnicity, as monsters and national pariahs. I wanted to place one of these men at the centre of a novel which explores what it means to live and narrate a life while so much of what you are supposed to be is fictionalised by others.

Q: You mentioned that this book is ‘a story about storytelling’. What made the picaresque style of writing Mister, Mister the most suited?

Mister, Mister is compelled by a strong central voice. These voices, when they come, provide any number of possibilities when writing. At times it becomes difficult to keep the reins and make sure the story doesn’t get overrun. The picaresque, in the tradition of Cervantes, Dickens, De Assis and others, is a generous vessel, where a life as tumultuous as Yahya’s can somewhat be held in place without spilling over too much.

Q: Both your novels continued to explore, in their own way, themes of national identity, political conflict and radicalisation. Are you keen to explore more of these themes in your next work?

Q: Both your novels continued to explore, in their own way, themes of national identity, political conflict and radicalisation. Are you keen to explore more of these themes in your next work?

I am drawn toward these themes because they’ve often generated ways to illuminate how we see of ourselves in relation to one another. As long as the rights and the terms by which national belonging is contested, not just in Britain but elsewhere, I think it’s worth writing about. The same holds for political extremism in all its manifestations. Whatever I write next will depend on which forms – novels, plays – can help clarify or perhaps problematise further.

Q: What’s your writing process like?

Without routine I’m nowhere. So: early mornings are best. 5am regularly, and couple of hours. I read in between sessions. I need to have consecutive days to write and build a head of steam for anything good to come. With two children that gets challenging. Much is owed to my partner, who is a very busy person herself. The truth is: what actually gets written comes down to what others are willing to forgive your absence for.

Q: Tell us in one sentence something that would spark a reader’s interest in your work?

Strange question. I’d like a different relationship with the reader, one where I promise to ignore their demands so I can write something they’ve never read before.

Q: What are you looking forward to at the Galle Literary Festival and being in Sri Lanka?

It will be my children’s first time in Sri Lanka. First time they will see their father’s books stacked in Sri Lankan bookshops. I’ll get to see them scratch their heads at the possibility that their own stories might travel as far as their ancestral homeland. That’ll be something.

The Fairway Galle Literary Festival is set to take place from 25-28 January 2024 at the Galle Fort. To purchase tickets and for the full programme visit www.galleliteraryfestival.com

British journalist, novelist and playwright, Guy Gunaratne’s debut novel In Our Mad and Furious City was the recipient of multiple literary awards (International Dylan Thomas Prize, the Jhalak Prize in the UK and the Authors Club Award) and was shortlisted for the Goldsmiths Prize and longlisted for the Booker Prize as well as the Orwell Prize for Political Fiction. Their new book Mister, Mister (2023) is a picaresque tale of a young poet named Yahya Bas who explores his identity and belonging while detained in the UK. At GLF 2024, Guy will discuss the book with Devana Senanayake and also join a panel with Yudhanjaya Wijeratne and Nayomi Munaweera on Radical Fiction.

British journalist, novelist and playwright, Guy Gunaratne’s debut novel In Our Mad and Furious City was the recipient of multiple literary awards (International Dylan Thomas Prize, the Jhalak Prize in the UK and the Authors Club Award) and was shortlisted for the Goldsmiths Prize and longlisted for the Booker Prize as well as the Orwell Prize for Political Fiction. Their new book Mister, Mister (2023) is a picaresque tale of a young poet named Yahya Bas who explores his identity and belonging while detained in the UK. At GLF 2024, Guy will discuss the book with Devana Senanayake and also join a panel with Yudhanjaya Wijeratne and Nayomi Munaweera on Radical Fiction. I’ve been writing since I was very young. I knew I wanted to tell stories and live a life entirely dedicated to art and in pursuit of works that can have some effect in the world. I think I understood this as a small boy. It felt as if I was singularly moved by books, film, music in ways other people just were not. And it was, at times, terribly lonely being the only one who didn’t simply want a good job and a salary when I grew up. I knew nobody in the arts. None of my family or friends had any such aspirations. So there couldn’t have been a plan, even if I’d wanted one. I had nobody to ask a favour. I had bags of conviction, however, and thanks to my mother, who made it permissible to believe that I might be the exception but only if I worked hard. A person either has to own who they are or not, I think.

I’ve been writing since I was very young. I knew I wanted to tell stories and live a life entirely dedicated to art and in pursuit of works that can have some effect in the world. I think I understood this as a small boy. It felt as if I was singularly moved by books, film, music in ways other people just were not. And it was, at times, terribly lonely being the only one who didn’t simply want a good job and a salary when I grew up. I knew nobody in the arts. None of my family or friends had any such aspirations. So there couldn’t have been a plan, even if I’d wanted one. I had nobody to ask a favour. I had bags of conviction, however, and thanks to my mother, who made it permissible to believe that I might be the exception but only if I worked hard. A person either has to own who they are or not, I think.  Q: Both your novels continued to explore, in their own way, themes of national identity, political conflict and radicalisation. Are you keen to explore more of these themes in your next work?

Q: Both your novels continued to explore, in their own way, themes of national identity, political conflict and radicalisation. Are you keen to explore more of these themes in your next work?