“ Covid helped collapse many of our social enterprises which provided livelihoods for vulnerable groups including widows, young women and men and poor villagers. Our commercial café and kitchen run by widows was closed for months. Our guest house on the northern tip of Wilpattu and run by young people in villages where the youth unemployment rate is a staggering 49%, closed for lengthy periods.”

“ Covid helped collapse many of our social enterprises which provided livelihoods for vulnerable groups including widows, young women and men and poor villagers. Our commercial café and kitchen run by widows was closed for months. Our guest house on the northern tip of Wilpattu and run by young people in villages where the youth unemployment rate is a staggering 49%, closed for lengthy periods.”

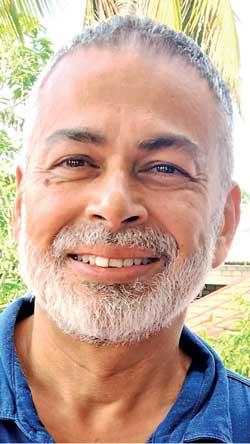

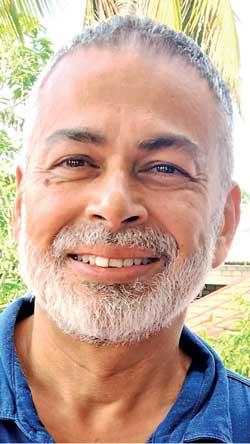

Jeremy Liyanage has worked in senior public policy and programme positions in local government in the Australian states of Victoria and Queensland for over ten years. His primary focus has been to influence institutional mindset for increased social and economic inclusion especially for those marginalised by current arrangements.

Jeremy has previously worked as a secondary school teacher in the public education system, community development worker at neighbourhood centres, community work consultant for the Anglican Church and a lecturer in the Tertiary and Further Education sector. Jeremy has a Bachelor of Arts (Semiotics), Diploma of Fine Arts (Etching), Grad Dip Education and a Masters of Social Welfare Administration and Social Planning.

Jeremy has engaged with a diverse number of groups including differently-abled people, migrants and refugees, Indigenous peoples, international students, prisoners, and more recently, asylum seekers in detention, in ways that build capacity and empower.

As the Executive Director of Bridging Lanka, his current challenge is to identify constructive roles for the diaspora in this post-conflict period of Sri Lanka’s history through community rebuilding projects in Mannar District in the war-affected Northern Province, as well as community dialogue processes in Australia. At its essence, Bridging Lanka seeks to bridge ethnic, religious and geographic divides through people-inspired action.

Q What made you come to Sri Lanka?

Q What made you come to Sri Lanka?

I was born in the Kandy Nursing Home and adored my life in Sri Lanka. I attended Trinity College. Things came to an abrupt halt when my parents were finally approved to migrate to Australia, after many rejections. Why rejections? Because my father was Sinhalese and at that time Australian migration was governed by the ‘White Australia Policy’. Following the policy’s lifting and the authorities able to trace an acceptable percentage of white blood in our family – my mother being Burgher, their application was granted.

Even at age 9 there was no way I was going to leave my beloved Ceylon. I took measures into my own hand and found a family in Kundasale who agreed to adopt me. Triumphantly, I returned home to inform my parents that they were free to leave as I had made alternative arrangements. Of course, parental authority prevailed and I was dragged kicking and screaming to Australia. This severance caused trauma that I knew would be resolved by reconnection with the land of my birth.

My first time back to Sri Lanka after my uprooting was in 1983 a few months after Black July when I was in my mid-twenties. I encountered, with unimaginable disbelief, the unfolding devastation of a country ripped apart by ethnic division. I vowed to prepare myself by extending my education in many different areas both formal and informal in readiness when that auspicious time would arrive when I could return to Sri Lanka to play a useful role in the country’s development.

Q Is Bridging Lanka your very own initiative and what gave birth to it?

Q Is Bridging Lanka your very own initiative and what gave birth to it?

It’s a long story. The idea was first birthed after the tsunami and our efforts to support the people of Akkaraipattu in the East. Emergency relief provisions especially for mothers with babies morphed into medium term community development activities. Then in 2007 while in the role of senior policy officer at Brisbane City Council in Australia, I was approached by the Business for Peace Alliance (BPA) in Sri Lanka to assist them, through the council, to reach members of the Sri Lankan diaspora. Their aim was to seek financial support from the diaspora for regional business development during the war time.

With the Lord Mayor’s support, we established a diaspora group, BrisPact, which later was formerly registered as Diaspora Lanka in 2010. Due to the Government of Sri Lanka regarding the word ‘diaspora’ as anathema, associating the word with the Tamil diaspora and LTTE only, our efforts to reframe ‘diaspora’ to embrace all Sri Lankans – Tamil, Sinhalese, Muslim and Burgher – failed abysmally. We were compelled to change our name to be more acceptable to the government. One of our directors, Visakha Tillekeratne suggested ‘Bridging Lanka’ – which in the end was a far better fit as we set about bridging ethnic religious and geographic divides through people-inspired action.

Q Is Bridging Lanka a passion or a job?

An easy answer! Through the vehicle of ‘Bridging Lanka’ a volunteer social service organisation registered with the National NGO Secretariat, a lifelong passion is being fulfilled. It is not a job but a way of life – from the heart. All involved from overseas work in a voluntary capacity. Local staff are paid.

Q How has Covid affected your activities?

Covid has had a fundamental impact on our operation. In one way we are lucky because we have built Bridging Lanka to be a smallish, agile and responsive agency which is able to surf the dynamic waves of life in Sri Lanka - a roller-coaster ride of epic proportions these days. Who could have predicted in 2018 the collapse of social cohesion in Kandy District that centred on Digana, costing the country its reputation as a peaceful multicultural society and also Rs 5 billion in lost tourist revenue? Who could have predicted the Easter bombings of 2019 or the Covid spectre of the last two years? Our ‘sense and respond’ approach has been far more appropriate than the usual ‘predict and control’ models.

Covid helped collapse many of our social enterprises which provided livelihoods for vulnerable groups including widows, young women and men and poor villagers. Our commercial café and kitchen run by widows was closed for months. Our guest house on the northern tip of Wilpattu and run by young people in villages where the youth unemployment rate is a staggering 49%, closed for lengthy periods. Our Donkey Clinic & Education Centre, where we treat injured donkeys and provide education services for the surrounding villages, and which has become one of Mannar’s premium tourist attractions, closed during the many lockdowns. Without the tourist dollar the centre’s existence faced precarious times. Our vegetables from local farmers we were supporting to go organic and sold to Cargills Food City also came to an abrupt halt. Our intensive work to recreate connection between Sinhalese and Muslim communities in the aftermath of the Digana conflict was disrupted due to severe travel and other restrictions under Covid.

But we have survived, paid our staff and live to tell tales of ongoing crises and achievement. We do not live in fear as we disbelieve the official Covid narrative. We have done our due diligence and scrutinised this ‘plandemic’ since March 2020. We do not subscribe to the views of the mainstream or social media with their lies, fear mongering and destruction. Strengthening one’s natural God-given immune system through nutritious food, exercise and fresh air, early treatment protocols and refusal to embrace the debilitating nature of the Covid propaganda are the best ways to stay healthy. Remember that even though many Covid cases are false positives there has been a 99.8% recovery rate.

Q Has the Sri Lankan government been of assistance to you in your endeavours or not? Do they support you financially in any way?

The Sri Lankan Government does not provide any funding for our work. While some committed and brave officers do exist within the many ministries with which we negotiate, generally speaking there is little support for our work. Our major interaction centres on jumping through endless government hoops to gain their approval to do good.

Q Could you elaborate briefly on your eight platforms of Endeavour?

Bridging Lanka’s work falls under eight platforms of endeavour and were identified as a result of extensive research and community engagement. Below is a brief overview:

Livelihood for vulnerable groups (inc. a cafe operated by widows, a merchandising business for young women, a one-stop-tradies-shop for young men)

Environmental health (inc. stop sand mining campaign, organic cultivation, chronic kidney disease, reforestation)

Urban improvement (inc. town planning, protection and rehabilitation of kulams, housing and drainage study, children’s park)

Social cohesion (inc. response to Digana anti-Muslim conflict, reconciling ethnic and religious divides)

Holistic education (inc. IT and English education, donkey assisted therapy, better parenting workshops, preschool)

Animal welfare (inc. rescue and treatment of injured donkeys, donkey clinic, sterilisation of street dogs)

Responsible tourism (inc. edu-tourism, volun-tourism, challenge-tourism)

Nurturing youth (inc. responding to alcohol and drug addictions, gyms, career guidance)

Q How many fulltime staff do you have?

We have nine full time staff. It is a challenge to find qualified staff in Mannar as the war and many other factors have historically disrupted young people’s pursuit of education – now Covid continues this trend, creating learning mayhem. Rather, we look for a strong, giving heart and a learning spirit. Then we build their knowledge and skill from the ground up. We nurture them in altruism, personal discipline and love of nature. We instil conservation values and encourage socially cohesive views. We expect multi-tasking and multi-skilled workers who can ride the many storms.

Q To date how many people have benefitted from your organization

We are not into bean-counting or producing info-graphics to impress. We are more interested in telling the lived stories of the people we support as they struggle to move in a positive direction. We don’t really know how many people we touch or have had an impact on. We work at micro and macro levels, from intensive 24 hour work with individual young people helping them to erase the curse of drug addiction to benefitting thousands through protecting kulams (lagoons) from illegal encroachment that leads to urban flooding and despair.

Q You talk of working with asylum seekers – are these people who have fled Sri Lanka and if so how do you manage this remotely

Our work with asylum seekers has lessened due to intense Covid restrictions especially in Melbourne and Sydney and also in Sri Lanka. Even my rhythm of spending three months each in Sri Lanka and Australia has been curtailed by the restrictions on international travel. The airfares, quarantine and testing costs are too prohibitive.

In the past we used to track the journeys of many Sri Lankan asylum seekers – from their lives in Sri Lanka, their perilous ocean travel, their precarious existence in an intermediary country, their incarceration in Australian detention centres, their eventual community release for those fortunate enough to be ‘let out’, their deportation and eventual return to Sri Lanka, imprisonment for a few and ongoing court cases based on leaving Sri Lanka illegally.

Q How badly is the North still affected by the war and the resultant trauma. I refer to both people and places.

The North and indeed the whole country is still undergoing trauma. There is no will to deal with the past, nor to reconcile differences. Without a ‘divide and rule’ agenda how could leaders ever hope to survive! Is there a place for Tamils and Muslims in Sri Lanka? They are barely tolerated let alone embraced as part of the Sri Lankan body-politic. As long as this inhospitality is government-sanctioned the trauma will continue to be supressed and find future release in another senseless uprising, or worse.

Q How long will it be for normalcy to resume if ever

Normalcy will not resume in the near future due to global, national and local agendas. The Covid fiasco continues to unfold with the double, triple and quadrupled vaccinated the main culprits being infected by Covid and also the main spreaders. Nationally, chronic food insecurity, out of control inflation driving up the cost of living to unaffordable levels, a country sans foreign exchange, and the ‘play thing’ of powerful geopolitical powers are combining to make a toxic cocktail of woes. Then, add to the mix the unscrupulous efforts of our political leaders to stoke the dangerous fires of sectarianism for their own political advantage and you have the perfect storm to rent asunder the social and economic fabric of this country. If the citizenry will not arise to oppose corruption and nepotism at every level, there is no more Sri Lanka of which to be proud.

“ Covid helped collapse many of our social enterprises which provided livelihoods for vulnerable groups including widows, young women and men and poor villagers. Our commercial café and kitchen run by widows was closed for months. Our guest house on the northern tip of Wilpattu and run by young people in villages where the youth unemployment rate is a staggering 49%, closed for lengthy periods.”

“ Covid helped collapse many of our social enterprises which provided livelihoods for vulnerable groups including widows, young women and men and poor villagers. Our commercial café and kitchen run by widows was closed for months. Our guest house on the northern tip of Wilpattu and run by young people in villages where the youth unemployment rate is a staggering 49%, closed for lengthy periods.” Q What made you come to Sri Lanka?

Q What made you come to Sri Lanka? Q Is Bridging Lanka your very own initiative and what gave birth to it?

Q Is Bridging Lanka your very own initiative and what gave birth to it?