“Pure Maths is still my first love. It is all to do with lines and points and planes and dimensions. Almost all my books have mathematics at their core. But I try not to talk about it. When I do, people look at their watch and say, ‘Heavens is that the time? I must dash!’”

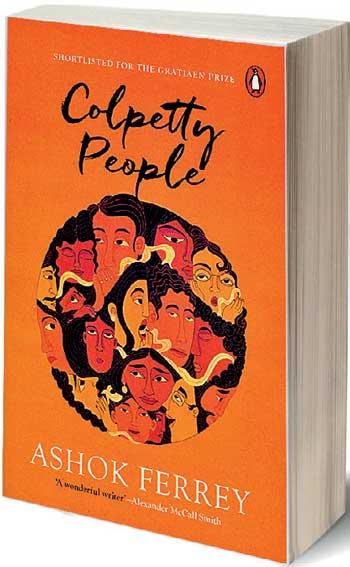

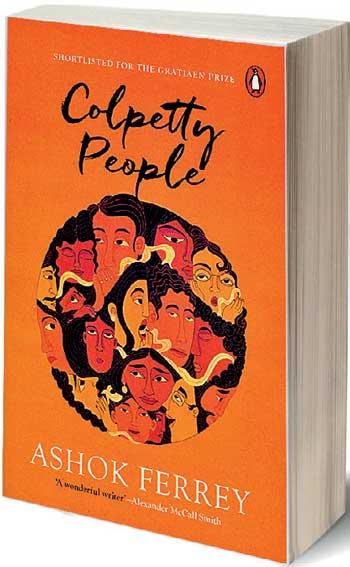

Today we welcome you to a new column which will profile authors from around the world. We start with prolific author Ashok Ferry who grew up in Somalia in the 1960s. He says he was very nearly sent to boarding school in Eldoret, in the Kenyan Highlands, where African runners go to train. If he had gone there, he is fairly sure he would have ended up a runner, not a writer. He has a Degree in Pure Mathematics from Christ Church, Oxford University and played Bridge for his college at Oxford. His team got to the University finals, but were beaten by a team of very sharp Americans from St. Anthony’s. Ashok says “Pure Maths is still my first love. It is all to do with lines and points and planes and dimensions. Almost all my books have mathematics at their core. But I try not to talk about it. When I do, people look at their watch and say, ‘Heavens is that the time? I must dash!’”

Q: What inspired you to become a writer?

Q: What inspired you to become a writer?It was a completely random sequence of events. My father was suffering from cancer. I remember bringing him back from the cancer hospital in Maharagama and putting him to bed. Then I went into the next room, found a Raheema’s exercise book and a stub of pencil, and that very first story (The Perfect House in Colpetty People) poured out of me in about half an hour. So I always tell budding writers: stress is good for you. It puts your mind on the front line. When you are fighting for your life, the best part of you comes to the fore, you are at your peak.

Q: Can you tell us about your journey to becoming a published author?

How to get published? It’s luck, luck and more luck, I’m afraid. In my case I was invited to a lit fest in Bhutan. There, I happened to read aloud the short story Last Man Standing about the tsunami. I think people were quite moved. At the end of it, a lady came up and offered to be my agent. Three months later she emailed to say she had four Indian publishers bidding simultaneously. I chose Random House, which is now Penguin.

Q: How would you describe your writing style or voice?

You have to write as if you’re speaking to one single person, in a lonely corner of some bar, at midnight. That’s when your true voice comes out. Don’t overdo it. There’s nothing worse than overcooked prose.

Q: Where do you draw inspiration for your stories or characters?

My goodness, Sri Lanka has the best raw material in the world! The stories you read or hear every day, they’re far stranger, far juicier than anything you could dream up. My great regret is that so many of them simply can’t be used – you’d lose all your friends if you did!

Q: Do you have any rituals or habits that help you get into the writing mindset?

As I said earlier, stress is good. And learning to isolate your mind from the madding crowd. Having no ritual is actually the best ritual. If you enshrine the act of writing (as you see actors do in films when they portray writers) you are being too precious about it; learn to de-mystify the act of writing, so it becomes as mundane as eating or bathing.

Q: How do you handle writer’s block or periods of creative drought?

Leave it be. Don’t agonize over it. Writer’s block can be quite a good thing, actually. It’s like leaving a field fallow for a season or two. The crop will be so much better when you finally do replant.

Q: Are there any particular themes or messages you aim to explore in your writing?

I have lived on three continents in my time: I have never come across a country as difficult to understand as Sri Lanka. I think what I am trying to do in my writing is to get to the bottom of what it means to be Sri Lankan. The gob-smackingly diverse, exquisitely complex process that we call life, here on this paradise island.

Q: How do you balance your personal life with your writing career?

With great difficulty is the honest answer. In my case I have a wife who is superb at running the day-to-day aspects of my life. It allows me to play the diva card; and I play it all the time, as she will tell you!

Q: Can you talk about any challenges you have faced in your writing journey and how you overcame them?

The flip side of living in Sri Lanka is that you have no anonymity. You’re watched closely, and nothing you do is ever right. So if you write a book every two years, you’re churning them out. If you take 7 years over a book, you’re a spent force, and all you can do is to give interviews to papers (!). You have to learn to ignore the chatter on the radio waves, not read reviews, not go online. The wisest thing I ever heard was that Arab saying: “The dogs bark, the caravan moves on.”

Q: Can you share any insights or teasers about your upcoming projects or works in progress?

I have just started a new novel. But don’t wait up, please.

Q: What is your take on Literary Festivals?

Ha! I was wondering when you would get to that one! I love them. By virtue of my venerable old age I have probably presented at more Lit Fests than anyone else in this country. Lit Fests are almost a new art form, because they bring to life your books in a very different way. I know lots of people who attend them, who would never dream of actually reading a book. At a Lit Fest you are fed the essence of the book, teaspoon by teaspoon. The hard work is done by the author and moderator sweating it out on stage. Your job is to snooze gently in the front row, waking up to take your medicine from time to time.

Q: What is your take on self-publishing?

It is an absolute necessity – I began my career self-publishing. But it is also what I call a necessary evil. Because publishing is a relatively cheap process here, we have all sorts of people publishing for entirely the wrong reasons: young kids do it because it’ll look good on their University CV. Then there are the one-hit-wonders – people who write a book just to tick a box. Once they’ve ticked it, they don’t feel the need ever to write again. But all in all, this flood of self-published books is a good thing: it helps keep the standard of the product high. And hey, if it makes someone happy that they are in print (even if nobody reads it), who are we to judge?

Q: What are your thoughts on the publishing industry in Sri Lanka?

In general, I think our standards are high, though we badly lack editors and proof-readers. I do wish though that publishers would show more discernment, instead of publishing any trash they are offered. But I realise that publishers have to eat too, so I can’t blame them too much.

Q: Name a book you have recently enjoyed reading?

Yellowface, by Rebecca Kuang. A marvellous insight into the Western publishing world!

Q: Tell us about a book you enjoyed reading as a child and the effect it had on you.

At the age of fourteen, at a British boarding school in deepest darkest Sussex, I got malaria. It was so unusual that the WHO in UK sent representatives to examine me. (I had in fact been bitten by a mosquito on holiday in Nigeria, but the symptoms manifested themselves only after I got back to school.) While I lay in bed enjoying my minor schoolboy celebrity, one of my teachers brought me a volume of Short Stories by Saki. I honestly can’t remember a book I enjoyed more. It was so killingly, cruelly funny.

Today we welcome you to a new column which will profile authors from around the world. We start with prolific author Ashok Ferry who grew up in Somalia in the 1960s. He says he was very nearly sent to boarding school in Eldoret, in the Kenyan Highlands, where African runners go to train. If he had gone there, he is fairly sure he would have ended up a runner, not a writer. He has a Degree in Pure Mathematics from Christ Church, Oxford University and played Bridge for his college at Oxford. His team got to the University finals, but were beaten by a team of very sharp Americans from St. Anthony’s. Ashok says “Pure Maths is still my first love. It is all to do with lines and points and planes and dimensions. Almost all my books have mathematics at their core. But I try not to talk about it. When I do, people look at their watch and say, ‘Heavens is that the time? I must dash!’”

Today we welcome you to a new column which will profile authors from around the world. We start with prolific author Ashok Ferry who grew up in Somalia in the 1960s. He says he was very nearly sent to boarding school in Eldoret, in the Kenyan Highlands, where African runners go to train. If he had gone there, he is fairly sure he would have ended up a runner, not a writer. He has a Degree in Pure Mathematics from Christ Church, Oxford University and played Bridge for his college at Oxford. His team got to the University finals, but were beaten by a team of very sharp Americans from St. Anthony’s. Ashok says “Pure Maths is still my first love. It is all to do with lines and points and planes and dimensions. Almost all my books have mathematics at their core. But I try not to talk about it. When I do, people look at their watch and say, ‘Heavens is that the time? I must dash!’” Q: What inspired you to become a writer?

Q: What inspired you to become a writer?