06 May 2022 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Scientific evidence proves link between Zika virus and microcephaly

Image courtesy - BBC

Zika virus was first isolated over 70 years ago from a rhesus monkey in the Zika forest of Uganda (hence the name!) and in 1952, human cases of zika virus infection were confirmed in Uganda and Tanzania. However, after this initial detection, only sporadic cases of zika virus infection were reported for the longest time and it was limited to a narrow geographical territory in Africa and Asia. However, in 2007 and 2013, two major Zika virus outbreaks were reported in Yap islands and in French Polynesia which was outside of the geographic territory, the virus was known to circulate. This indicated that the Zika virus was crossing the pacific and expanding its territory.

Zika virus was first isolated over 70 years ago from a rhesus monkey in the Zika forest of Uganda (hence the name!) and in 1952, human cases of zika virus infection were confirmed in Uganda and Tanzania. However, after this initial detection, only sporadic cases of zika virus infection were reported for the longest time and it was limited to a narrow geographical territory in Africa and Asia. However, in 2007 and 2013, two major Zika virus outbreaks were reported in Yap islands and in French Polynesia which was outside of the geographic territory, the virus was known to circulate. This indicated that the Zika virus was crossing the pacific and expanding its territory.

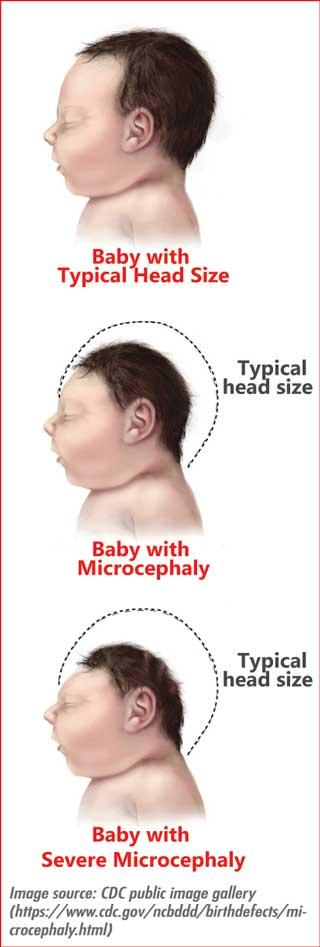

By February 2016, world health organization (WHO) declared Zika virus outbreak as a public health emergency of international concern because of the mounting scientific evidence pointing towards devastating outcomes of Zika virus infection in pregnant women: infants born with microcephaly (smaller head than normal) and other congenital deformities affecting mainly eyes and brain.

Zika virus belongs to the family of flaviviruses. Morphologically, zika virus is similar to the Dengue virus, composing of a protein capsid that encapsulate the viral RNA genome which is in-turn encapsulated by a lipid membrane called viral envelope. Viral envelope contains a protein called glycoprotein that allow viral particles to gain access to the host cell.

Zika virus is transmitted to humans primarily through infected mosquito bites. Mosquito vector for Zika virus is same as for the Dengue virus; Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, two mosquito strains that are rampant in Sri Lanka. Apart from mosquito bites, transmission of Zika virus through sexual intercourse and contact with infected body fluids (ex. blood transfusion and organ transplantation) have also been reported. The Zika virus can be transmitted from infected mother to her fetus during pregnancy, increasing the risks of birth defects making Zika virus infection potentially more concerning than Dengue virus infection. Zika infection during pregnancy can also cause preterm births, miscarriages, and stillbirths.

Symptoms of zika virus infection are like a milder form of Dengue infection, with rash, fever, headache, joint pain, muscle pain and red eyes. Patients will be asked to get plenty of rest, increase fluid intake to prevent dehydration and use acetaminophen (paracetamol) to reduce pain and fever. It is important not to use aspirin or other non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) to manage fever until Dengue infection is ruled out to reduce the risk of bleeding.

Why does Sri Lanka need to be wary of Zika virus?

Zika virus has shown patterns of migration from the narrow equatorial strip in Africa in which it was initially detected to Southeast Asia (migration occurred somewhere between 1945-1960) and crossing pacific to Americas and further migrating towards the continental united states.

Sri Lanka’s closest neighbor, India reported four cases of Zika virus infection for the first time in 2017 that spread to other states including Kerala by 2020. Given the significant movement of people between Sri Lanka and India or other Southeast Asian countries, if Zika has not already arrived in Sri Lanka, it is only a matter of very short time till it comes knocking at our doorstep. As Aedes mosquitoes are capable of breeding all over the country, Zika virus will have no difficulty in spreading throughout Sri Lanka. A Zika virus outbreak will have a devastating socio-economic impact on Sri Lanka. Risk to pregnant women due to zika virus associated congenital malformations will undoubtedly be the biggest worry. Experimental data gathered using mouse models indicate that Dengue virus specific antibodies may enhance maternal-to-fetal Zika virus transmission and increase damages to the placenta and cause severe microcephaly conditions. These findings suggest an enhanced risk for many expectant mothers in Sri Lanka that could result in a severe pregnancy outcome. This is because a significant fraction of our population has existing immunity against Dengue virus due to prior contraction of one or more of Dengue viral serotypes circulating in Sri Lanka.

Therefore, if a Zika virus outbreak does occur in Sri Lanka, families and the country will have to come to terms with the massive socio-economic costs of caring for these sick infants.

What can we do as a country to protect ourselves from Zika virus?

It is imperative that we properly evaluate the threat of Zika virus to our nation. We cannot rule out the possibility that Zika virus may have already entered Sri Lanka unless we carry out a thorough population based serosurvey (a population study that involves testing blood serum for presence of antibodies against a specific pathogen. Ex. Zika virus) which will indicate whether the virus has been silently spreading in the country.

Improving testing capacities of molecular diagnostic laboratories that can conduct RT-PCR tests for Zika virus is very important. Patients reporting symptoms of fever, headache, rash but are testing negative to Dengue and chikungunya virus can be tested for Zika virus infection. Further, incidences of microcephaly and congenital neurological deformities, detected during ultrasound scans of the fetus needs to be reported to a single national center to determine appearance of clusters that may have been influenced by a zika virus outbreak. Similarly, cases of Guillain-Barre’ syndrome in adults should also be reported to a single center. These cases can be followed up with serological studies to determine the presence of antibodies against Zika virus to confirm a positive infection.

Conducting routine surveillance to detect presence of Zika virus in Aedes mosquito populations and larvae throughout the country will also provide valuable data regarding the spread of virus. As there is no approved vaccine or other therapeutic against Zika virus, controlling the vector population (Aedes mosquitos) and preventive measures against mosquito bites will still be the most effective way to curb Zika virus as in the case for Dengue virus.

Health authorities must continue to inform and educate public of Zika virus infection, especially in periods where outbreaks are reported in other countries. Travel advisories to limit travels to regions where Zika virus is actively spreading is important. Public especially needs to be aware of the sexual transmission of zika virus. Sexually active men and women must be counselled during an active outbreak to make informed choices about pregnancy.

While it may be impossible to prevent entry of Zika virus to Sri Lanka, if we implement routine surveillance for the zika virus among people and among vector population, increase diagnostic capabilities in laboratories to support early detection, adapt vector control and preventive measures successfully and improve public awareness, we will be able to mitigate adverse effects of a zika virus outbreak.

(The writer is a Lecturer at the Department of Chemistry, University of Colombo)

20 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

20 Dec 2024 3 hours ago

20 Dec 2024 4 hours ago

20 Dec 2024 5 hours ago

20 Dec 2024 5 hours ago