25 Jul 2024 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

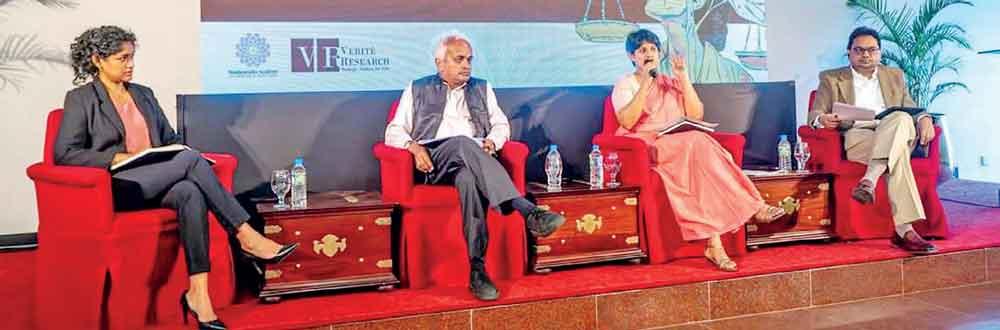

Subhashini Abeysinghe, Research Director at Verité Research, is seen airing her views at the discussion on “The Accountability Imperative for Sri Lanka’s Recovery: Practical Solutions for Inclusive Growth,” which was organised by Verité Research and held on July 16 at the BMICH. The others in the picture from left are Sankhitha Gunaratne, Prof. Shanta Devarajan and Dr. Nishan de Mel

Sri Lanka was once one of the most successful economies in South Asia, boasting a higher GDP per capita than any other sizable South Asian country. Its human development indicators were the envy of the world, with a child mortality rate comparable to that of the US and nearly 100% secondary school enrollment, significantly surpassing its regional peers. Additionally, Sri Lanka has maintained an uninterrupted democracy since gaining independence.

Sri Lanka was once one of the most successful economies in South Asia, boasting a higher GDP per capita than any other sizable South Asian country. Its human development indicators were the envy of the world, with a child mortality rate comparable to that of the US and nearly 100% secondary school enrollment, significantly surpassing its regional peers. Additionally, Sri Lanka has maintained an uninterrupted democracy since gaining independence.

Given these achievements, how did Sri Lanka end up in a severe economic crisis? If the government performed so well in the past, what went wrong? More importantly, how can the nation achieve inclusive growth moving forward?

These were among the opening remarks made by Prof. Shanta Devarajan in his keynote address at the discussion on “The Accountability Imperative for Sri Lanka’s Recovery: Practical Solutions for Inclusive Growth,” organised by Verité Research on

|

Prof. Shanta Devarajan is seen making his keynote address |

July 16. Prof. Devarajan is a Professor of the Practice of International Development at Georgetown University and a Non-Resident Fellow at Verité Research.

Accountability

According to Prof. Devarajan, the answer to the three questions raised above is ‘accountability’, which is of two forms. Firstly, ‘accountability in markets,” meaning that firms in competitive markets should be accountable to the market. Secondly, ‘accountability in government’, where governments should be held accountable by their citizens.

“Both these types of accountability have been missing in Sri Lanka for the past 70 years. This has had a corrosive effect on the economy and society, contributing significantly to the current crisis. To resume growth, we need to reintroduce accountability,” Prof. Devarajan asserted.

Trade Liberalisation

Prof. Devarajan underscored a notable instance where Sri Lanka moved towards market accountability and achieved exceptional results. “When Sri Lanka liberalised its trade regime in the 1970s, the growth rate surged and unemployment dropped. Recently, however, the trade ratio has been declining. Protectionist policies that block imports to favour certain domestic industries have been on the rise, leading to increased corruption. It’s not a coincidence that the IMF’s Governance Diagnostic Assessment identified the two most corrupt agencies of the Sri Lankan government: the Inland Revenue Department and the Sri Lanka Customs,” he noted.

“So, my first policy recommendation is to liberalise trade. We’ve done this before and seen that it works. When Sri Lankan entrepreneurs are held accountable to world markets, they deliver. We can reverse the trade ratio by lowering import barriers,” Prof. Devarajan emphasised.

Subhashini Abeysinghe, Research Director at Verité Research, shared that one problem in trade liberalisation is the ability of firms to trade and invest in Sri Lanka, as their efficiency is hindered by numerous regulatory and other barriers. “If you have many domestic barriers that increase the cost and complexity of trading across borders, simple tariff liberalisation without addressing these barriers might reduce the benefits. There must be complementary policies,” she stressed.

Abeysinghe further argued that trade facilitation and trade liberalisation should happen simultaneously as they complement each other. She noted that the country has experienced periods of progressive liberalisation followed by reversals. “One of the problems is that we haven’t sought public support, which leads to resentment and resistance which are exploited for political gain. We need to sustain reforms, prevent reversals, and gain public support through consultation,” she said.

Addressing corruption within Sri Lanka Customs, Sankhitha Gunaratne, Head of Governance and Anti-Corruption at Verité Research, remarked, “Corruption within customs remains a huge problem for businesses in the export and import industry. There’s significant rent-seeking behaviour within customs, leading to an institutional culture of corruption, which has been resistant to reform for years. It appears that the government has also been unable to address this issue,” she observed.

As for solutions to counter such corruption, Gunaratne suggested that industries should unite to resist extortive practices. She also recommended that large companies start recording instances of corruption and disclose them publicly.

Allow farmers to grow what they want

In Sri Lanka, agriculture contributes the least to GDP, and agricultural productivity has shown minimal growth. Prof. Devarajan noted that most farm households produce paddy, which is the least productive and least lucrative crop in terms of rupees and output per acre. All other crops are more productive and profitable than paddy.

“So why do they continue to grow paddy? Because of the Paddy Lands Act of 1958, which mandates paddy cultivation. There are also other policies that favour paddy farmers exclusively. This needs to change. We cannot continue to keep these farmers impoverished by forcing them to grow paddy. This is unacceptable. The policy recommendation is to make these farmers accountable to markets, not the government. Let them compete in the markets and grow whatever they want,” he opined.

Abeysinghe stated that heavy government involvement in agriculture has created an inefficient and ineffective input market, significantly constraining farmers’ ability to switch to other crops. “To make informed choices, farmers need access to the right inputs and information about demand and prices. We frequently see gluts or shortages due to inefficient information flow, preventing farmers from operating profitably. Complementary reforms and initiatives are necessary to equip and empower farmers to switch to other crops and make agriculture a profitable livelihood,” she emphasised. Dr. Nishan de Mel, Executive Director of Verité Research, added that the country hasn’t adequately explored the potential for a productivity transformation in agriculture, given that a large percentage of the population is involved in it. “Approximately 24% of our workforce is in agriculture, producing less than 8% of GDP. Enhancing productivity in agriculture is one of the most promising opportunities for Sri Lanka’s success. There is significant potential for a massive productivity shift in agriculture,” he said.

Eliminate Energy Subsidies

Prof. Devarajan underscored the longstanding issue of fuel and electricity subsidies in Sri Lanka, noting that the overwhelming majority of these subsidies benefit the wealthy. “In Sri Lanka, it is estimated that 70% of subsidies go to the richest 30% of the population,” he explained.

“Paradoxically, by eliminating the subsidy and raising the price of electricity, you might actually help the poor more because then at least they will get some electricity. These subsidies are perverse; they tell the poor that if you use these services, you get a subsidy, inadvertently encouraging their use. We should eliminate subsidies and replace them with targeted cash transfers. If you give them a cash transfer, they can spend it on whatever they need, not just electricity or fuel,” he suggested.

Addressing corruption in the procurement process, Gunaratne noted that allowing unsolicited proposals has led to massive corruption and high energy prices. “There is no need to engage in non-competitive processes. In fact, the procurement guidelines allow for Cabinet discretion to approve unsolicited proposals only under specific conditions. We are breaching our existing laws and best practices, resulting in significant losses that are then passed on to the poor,” she stated.

Targeted Cash Transfers

Sri Lanka’s targeted cash transfer programme, Samurdhi, currently reaches only 40% of the poor. When the government transitioned to the ‘Aswesuma’ programme’ and removed those who were not qualified to receive cash transfers, it resulted in protests which were eventually exploited for political gain, commentedProf. Devarajan.

“My colleagues at Verité Research have proposed a simple, transparent method of targeting based on electricity consumption. If you consume less than 60 kWh of electricity a month, you qualify for the Samurdhi transfer. This approach can reach 81% of the poor. While not perfect, it is an improvement over the current system and tougher to manipulate. So, replace ‘Aswesuma’ with a simple criterion that is transparent and targets the poor,” he suggested.

Addressing the issue of maternity leave benefits and its impact on women’s discrimination in the labour market, Abeysinghe explained, “One reason women face discrimination is that when they have a child, the company loses the employee for a considerable period and must also pay their salary during that time. This is a social cost that should be borne by society, especially since many countries, including Sri Lanka, face a rapidly ageing population and declining child population,” said Abeysinghe.

Sri Lanka is a signatory of the global Maternity Protection Convention, which does not mandate that maternity leave costs be borne solely by companies. Instead, it emphasises that maternity leave benefits should be provided through a social security system. Addressing this issue would benefit the country economically, Abeysinghe added.

Dr. de Mel noted that evidence shows eliminating employers’ obligation to pay for maternity leave reduces discrimination and can improve women’s labour market participation by 10-20%.

Make Teachers Accountable to Learning Outcomes

“Our education system is the envy of the world. Our secondary school enrollment rate is practically 100%. Children are attending school for ten to eleven years, but the problem is whether they are actually learning anything. This is a problem especially in provincial schools,” said Prof. Devarajan.

He pointed out that the teacher absentee rate is particularly high in provincial areas. A 2006 survey revealed that 64% of households reported positive private tuition expenditures. And 60% of the poorest quartile also reported positive private tuition expenditures. “Why is the teacher not accountable? Because the teacher is accountable to the government, not to the student. We need to make teachers and schools accountable for learning outcomes,” Prof. Devarajan emphasised.

Drawing examples from other countries, he suggested introducing a voucher system similar to Colombia’s, enabling students to choose between private and public schools. This approach, he argued, would improve learning outcomes for the poor. Whichever school students choose would be paid for. “We found that schools were actually trying to attract students,” he observed.

Discussing the establishment of private universities in Sri Lanka, Prof. Devarajan noted, “Currently, Sri Lanka has the lowest tertiary enrollment rate among middle-income countries due to having only one type of university: public universities. The number of placements is limited by available funds”. He added that about 50% of public university enrollments in Sri Lanka come from the richest 20% of the population.

Accountability for government borrowing

Discussing foreign borrowing, Prof. Devarajan noted, “The composition of foreign borrowing between official creditors and private creditors has shifted over the last 10 years in favour of International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs). There were almost none around 2005, but now they account for about a third of the borrowing. This shift is beneficial because it holds the government accountable. The government cannot mismanage funds without consequences, as evidenced when Sri Lanka’s fiscal deficit soared, leading to a downgrade. If there’s a chance the government might misuse funds, it’s best to ensure they borrow from ISB holders.”

Prof. Devarajan also proposed separating foreign investments from foreign policy.

Highlighting the role of digital systems in driving accountability, Gunaratne emphasised that digitisation reduces human interaction, thereby minimising corruption and rent-seeking behaviour. “Digital systems can be a crucial tool in combating corruption. The Governance Diagnostic Assessment includes numerous digitization recommendations,” she noted.

She further stated that some of the resistance and agitation seen in the ‘aragalaya’ (struggle) has moved into formal spaces. “Accountability is hard-fought and hard-won. We must continue to strive for it at every opportunity,” Gunaratne concluded.

27 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

27 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

27 Dec 2024 3 hours ago

27 Dec 2024 3 hours ago

27 Dec 2024 4 hours ago