23 Mar 2022 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Mama, why am I going with this strange man?

For your safety, my dear

But Mama, he scares me, he’s hurt me, everywhere, I don’t feel safe

Oh honey, it’s okay. It’s what all girls do.

But-but...I love you, I love Papa, I don’t wanna leave you.

It is your duty, child, we need the money. If you love us, go.

So goes the poem by one Sam.

For thousands of young girls across Sri Lanka, their wedding is a far cry from happily ever after as parents marry off their daughters due to various reasons such as poverty, tradition and gender inequality.

off their daughters due to various reasons such as poverty, tradition and gender inequality.

The debate on child marriages in Sri Lanka has been focused too much on Muslims. But, in reality, the evidence shows that the child marriage problem is not a Muslim or Sinhalese problem, but a national problem.

At its core, child marriage is a violation of child protection and human rights. Whatever the reason, child marriage compromises a child’s development and severely limits her or his opportunities in life.

Sujani from Kanugahawewa, Anuradhapura said she didn’t realize how big of a commitment she was making. “I cried because I was too young to get married. I didn’t want to, I didn’t understand the meaning of marriage, I was filled with fear,” she continued. The numbers show that Sujani’s story is not far from reality. Each year, 15 million girls are married before the age of 18 around the world. That is one girl every two seconds.

"Child marriages will cost developing countries trillions of dollars by 2030, says a new report published by the World Bank and the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW)"

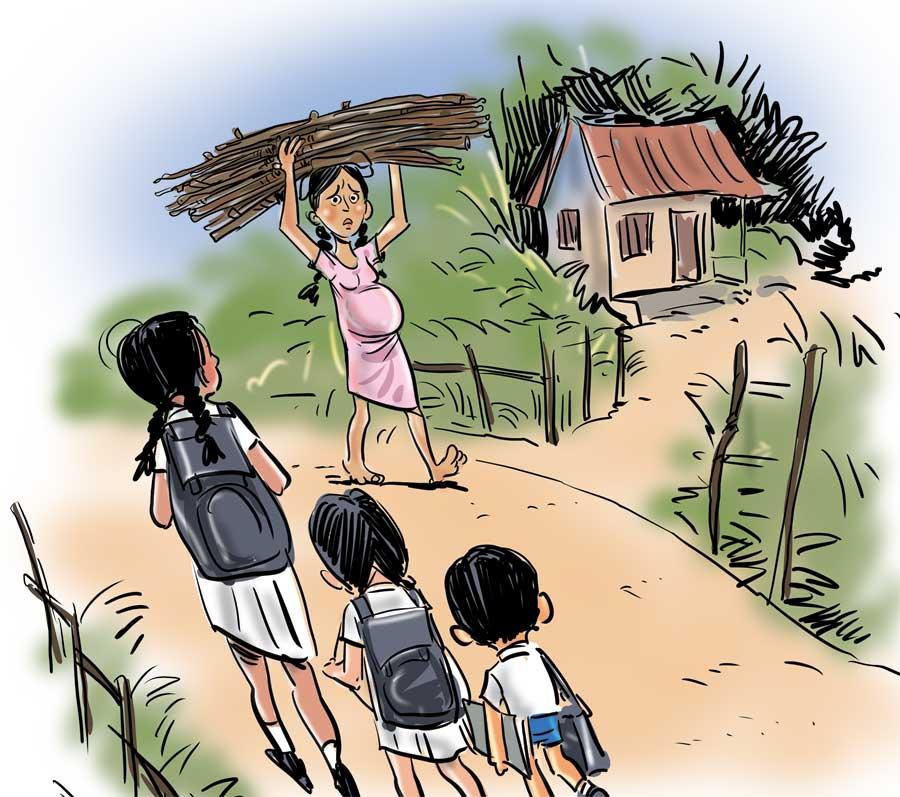

Sujani and her two younger sisters would go to bed hungry if they didn’t have a lucky day. When her parents separated when she was just nine years old, life got even harder for the family. It was up to Sujani’s mother to provide for herself and her three young daughters. Then, Sujani’s mother flew to Lebanon to work as a housemaid after sending her three daughters to their grandmother’s.

Remittances of migrant workers including tens of thousands of women like Sujani’s mother, working as housemaids in the Middle East, have been the largest single source of foreign exchange inflow in Sri Lanka’s balance of payments (BOP) over the past decade.

From 2001 to 2020, about 8% of Sri Lanka’s annual gross domestic product came from overseas citizens sending money home. Workers’ remittances constitute almost 100 per cent of the inflows to the secondary income account of the external current account.

“I was supposed to be in school at the time I got married,” Sujani, now 30, mother of two daughters, told Daily Mirror. “I was 15-years-old when I got married. Sujani knew that her mother couldn’t afford to feed her, buy clothes for her, or pay her school fees, and she felt that if she refused to get married, she wouldn’t have anywhere else to go.

|

The absence of the mother, it is argued, leads to the neglect of children, resulting in school drop-outs, early marriages, and vulnerability to sexual abuse. Even though the Family Background Report (FBR) circular bans women with children less than five years of age from migrating for work, it does not cover women with teenage daughters. |

In her new role as a wife, Sujani stopped going to school, and instead took care of her husband. She and her husband struggled to earn enough to eat. But the greatest loss, for Sujani, was her freedom. “When I was staying with my family I was free to do what I wanted to do. Now in the house, I was taken to, I wasn’t free. I was scared because he refused freedom for me to do anything, and only he decided what should be done.”

|

Instead of getting an education, Sujani spent her days sweeping, washing clothes, washing dishes, collecting firewood, and cooking. After three months, she realised she was pregnant. |

Women in such situations are more likely to report no contraceptive use and are at a greater risk of unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections including HIV and cervical cancer. Among Sri Lankan women aged 15–19 years, pregnancy-related death is the second leading cause of death. Physical immaturity for childbearing, combined with lack of power, information, and access to services, place them at a heightened risk of maternal morbidity and mortality. “When I was pregnant I felt so much pain because I wasn’t ready to conceive at that age,” she said.

At 16, far too young to know about childbirth, or how to take care of a baby, Sujani went into terrifying and painful labour. “I did not know how to deliver a baby. I was just a child. And I wouldn’t like anyone who is 15 to go through what I have been through.”

When asked about her childhood dreams, she said she knew she couldn’t have big dreams due to financial difficulties. “When I looked at other kids of my age, I felt desperate and helpless. I knew without the support of my parents, I could not reach up the ladder. We may have committed sins to get a life like this.”

|

Evidence shows that the more education a girl receives, the less likely she is to marry as a child. Sujani said, “but, I won’t let that happen to my daughters. I expect them to study well and go up the ladder of life. If my daughters could get an education, their lives would be different from mine.” |

Sujani lived in a clay house for nine years before she received funds to build a house from the Government Samurdhi programme. However, a wall of the house built from Samurdhi funds suddenly collapsed. That is when the Air Force officers came in and built her the house completely. She is grateful to them. “Now we are living under a roof even on empty stomach without getting wet from the rain. With my two daughters, now we can close doors and sleep peacefully at night.”

Daily Mirror studied the statistics maintained by the Registrar General’s Department. The data revealed that between 2005 and 2015, more than 105,000 births by mothers aged below 18 have been reported in the country. This number even included births by mothers who were as young as 13 at the time of giving birth.

However, there is a shortage of Government data. The Government has to collect data and find the shortcomings based on which it will be possible to adopt and implement policies as well as to invest. Apart from the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act (MMDA) which is currently subject to reforms, there is no shortage of laws and policies in the country to eradicate child marriage. However, there is a lack of implementation.

Meanwhile, a new report published by the World Bank and the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) stated that child marriages will cost developing countries trillions of dollars by 2030. In contrast, ending child marriage would have a largely positive effect on the educational attainment of girls and their children, contribute to women having fewer children and later in life, and increase women’s expected earnings and household welfare.

Illustrations by Namal Amarasinghe

08 Jan 2025 51 minute ago

08 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

08 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

08 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

08 Jan 2025 3 hours ago