Plantation workers in Hill Country

Chrystlers Farm housing scheme

- Estate workers have been living in line rooms for years and it has become their lifestyle

- People deprived of clean water and electricity

- Underage marriage, single mothers, prostitution, drug and alcohol addiction and domestic violence are major issues among Estate workers

- Women continue to wear cloths instead of sanitary napkins

Cooler climes have returned to the hill country. Mist-draped mountains reflecting on clear waters, endless greeneries and picturesque tea estates present a magical landscape. But unlike the unpredictable climate, the

lives of the majority plantation workers have stagnated for years. According to the 2012 Census, 4.5% of the Sri Lankan population live in estates.

The percentage of the hill country Tamils making up the plantation population in the years 1911 and 2001 was 77% and 88% respectively.

Having fought long struggles to obtain citizenship, voting rights amidst strong waves of discrimination, the population has achieved certain victories, but that’s insufficient to bring a smile on their faces. At the upcoming Parliamentary Election, as many as 275 candidates will contest from the Nuwara Eliya District alone. Despite the election, life goes on with a majority of them sending blessings to the Ceylon Workers Congress (CWC), the trade union / Party that has looked after them for years.

During a visit to the hill country, the Daily Mirror observed many underlying issues that continue to add pressure to the lives of plantation workers in the hills.

Birth of trade unions

Norwegian anthropologist Oddvar Hollup in his study on Trade Unions and Leadership among Tamil Estate Workers in Sri Lanka writes how white planters imported coolies from South India under the Kangani System, back

|

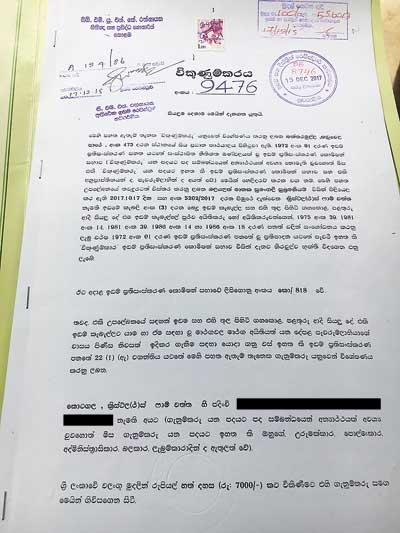

Deed given to families in Chrystlers Farm

|

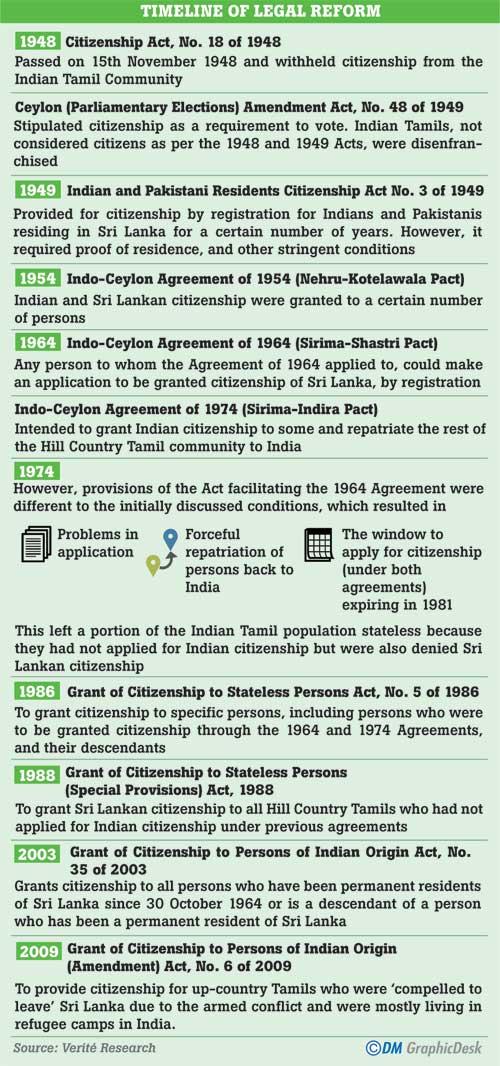

in the 1800s. The Head Kangani was an elderly person of a higher caste. Once it was abolished in the mid 1960s, the union leaders (talaivars) took the lead. The majority of immigrants were Indian Tamils, either landless agricultural workers or poor peasants and tenants. More than half of them belonged to the Paraiyan and Pallan castes. When Sri Lanka achieved independence in 1948, one million Indian Tamils were disenfranchised due to restrictive citizenship laws which were enacted. They obtained citizenship and voting rights following a gradual process while some of them were repatriated to India as a result of the Sirimavo-Shastri Pact of 1964. The living conditions of the estate workers, their low socio-economic status and their relations to the means of production make them a plantation proletariat depending on selling their labour for low wages. Faced with several constraints where they lack citizenship, land, houses, mobility and possibilities for alternative adaptations, estate Tamils needed trade unions as brokers and patrons.

The CWC was the largest trade union in the country but the leadership problem within CWC resulted in a few more members breaking away to form the Democratic Workers Congress (DWC), National Union of Workers (NUW) and several others.

The formation of new trade unions such as Lanka Janatha Estate Workers Union (LJEWU) and Ilankai Tolailalar Kazhagam (ITK) by political parties such as the United National Party and Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) led to a fragmentation of the labour movement within the estate sector, limiting trade unions’ role and power to act as united pressure groups. Hollup states that the political affiliation towards the UNP, which was the ruling party at the time is responsible for the reformist policies and strategies that were adopted by CWC and LJEWU, the two main trade unions at the time. Caste distinctions influenced trade union membership in a rigid manner. The common interests of the workers didn’t create a uniting force. Sometimes estate managements encouraged more trade unions to be formed, so that there would be more rivalries among unions, thereby imposing a divide and rule policy. He concludes by saying that the estate worker has a long way to go. Twenty nine years later, one can again say that the estate worker has a long way to go. But for how long is the question!

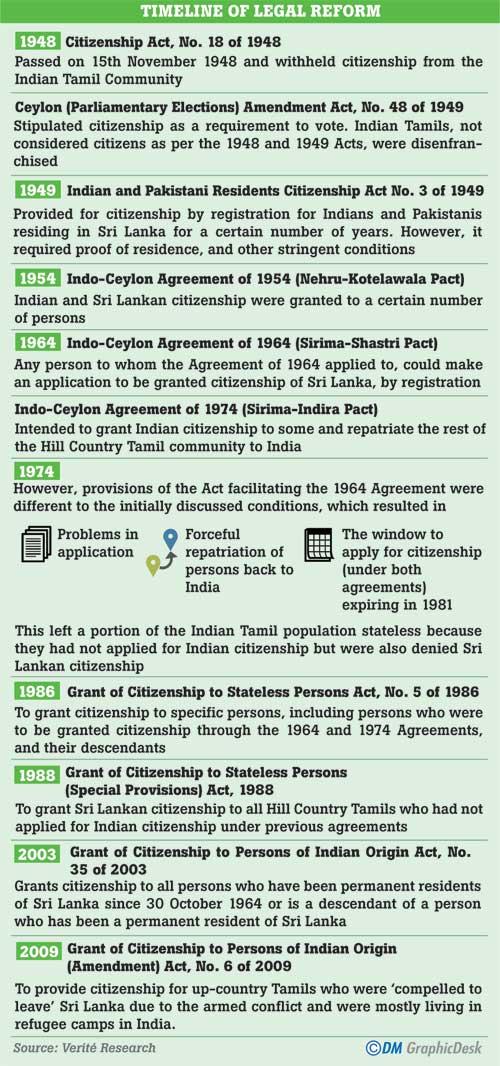

Formal citizenship as meaningful citizenship

Sri Lanka granted citizenship to over 90,000 stateless persons through the enactment of the Grant of Citizenship to Persons of Indian Origin Act No. 35 of 2003. The main beneficiaries of this legal reform project was the hill country Tamil community. However, according to ‘hill country Tamils of Sri Lanka : Towards Meaningful Citizenship’, a study done by Verite Research, despite positive law reforms, hill country Tamils remain one of the most discriminated against and economically, socially and politically marginalised communities in the country. Statelessness fosters conditions of marginalisation and insecurity. The study however highlights four benefits to the citizen reflected in meaningful citizenship ;

- Citizenship identifies an individual as a member of a state in terms of a formal legal framework

- Citizenship denotes a political relationship, whereby a citizen has a ‘voice’ in effecting political action and is a stakeholder in institutions that can develop law and policy

- Citizenship can be a gateway to enhanced economic welfare and security

- Citizenship relates closely to ideas of community and identity

While statelessness presents enormous challenges to human rights, the link between statelessness and

|

Estate workers in Norwood sharing a lighter moment during their tea break (Pix by Kamanthi Wickramasinghe)

|

discrimination is so strong that statelessness cannot be eradicated unless discriminatory societal attitudes are comprehensively tackled. Therefore, formal citizenship alone is inadequate in addressing obstacles to rights and development that these communities face. Deep-rooted structural barriers including continued discrimination, poverty and political isolation stand in the way of inclusion. The study further identifies structural state discrimination, dependency on plantation companies and brokerage of trade unions as main drivers of disadvantage faced by the Hill Country Tamil community. In most instances, the plantation companies carry out state-like interventions and therefore, their worries and requests are granted by the company rather than the state. Meaningful citizenship for this community cannot be achieved without respecting, protecting and promoting their human rights as articulated in the international law and the Constitution of Sri Lanka.

Workers’ woes

The Daily Mirror visited several areas in the hill country from Norwood to Maskeliya, Hatton, Dickoya, and Kotagala in the Nuwara Eliya District which is a stronghold of many trade unions. Estate workers seem to be loyal to the CWC although some claim that they haven’t enjoyed any benefits. Here’s what a few of them had to say:

Nothing fruitful has happened

Nothing fruitful has happened

S. Thilogamani (40) is a mother of two children, studying in 5th and 8th grades respectively. “It has been 10 years since my husband passed away. I have no house and live in the maternal house with my brother’s family. The younger child doen’t have space to sleep inside the room. Although our details were noted by supporters of one party nothing has happened. If we don’t work we only get Rs. 6000 for a month. We pluck between 16-20 kilograms of tea leaves daily. We support politicians during every election, but nothing fruitful has happened so far,” she complained.

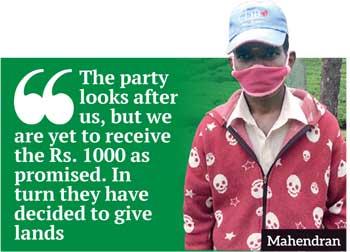

CWC offers care

With 15 years of experience in the field, Mahendran, the Kangani at St. John Tillery (Lower Division) says that workers received the Rs. 5000 allowance twice. “The CWC looks after us, but we are yet to receive the Rs. 1000 as promised. In turn they have decided to give lands to the people to develop and get paid by respective companies. But we don’t have an income for this because the plants have to be maintained from our own money,” he said.

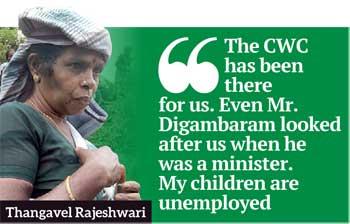

Have to worship politicians

However, Thangavel Rajeshwari says she will elect someone who has looked after them. “The CWC has been there for us. Even Mr. Digambaram looked after us when he was a minister. My children are unemployed. I work on a contract basis since I have passed retirement

age. So I’m paid Rs. 40 per kilo. We can’t find employment in another profession after retirement because we have been plucking tea all our lives. Other than that we can be engaged in babysitting or domestic work. Our husbands too are unemployed and therefore if we are given plots of land to solve the Rs. 1000 issue we would have to double our efforts to maintain them. Our line rooms are dilapidated and during the slightest rain there are leaks all over. If we want a roofing sheet we have to worship politicians. But all this happens while the CWC takes care of us. We are left out of the estate system after we retire, but the CWC is always with the workers,” said Rajeshwari.

She further said that the Rs. 5000 allowance given by the Government was received only by those who didn’t work. “Those who worked didn’t get it. They also gave us essential items worth Rs. 5000,” she recalled.

Not even a bamboo stick

We also visited the estate workers living in line rooms at Malligapu Estate, Hatton. They had mixed views. “I’ll vote for the UNP because the CWC hasn’t done anything for me. There was a leak at my house and I wanted to get a pipe. My request fell on deaf ears and they couldn’t even get me a bamboo stick,” claimed Ramasamy.

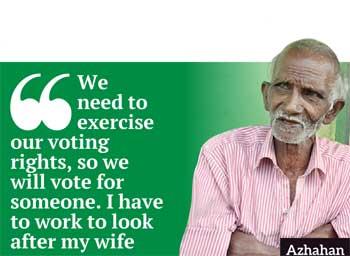

Need to exercise our voting rights

However, Azhahan on the other hand had been a CWC supporter from a young age. “I have been in the Union ever since the time of Soumiamoorthy Thondaman. I have even given sandapanam (membership fees) to people. We need to exercise our voting rights, so we will vote for someone. I have to work to look after my wife who is over 80 years old. Mr. Digambaram handed over some houses with water and electricity, but we have to complete the rest of it,” said Alahan.

“Please give me a call”

Once they retire they are unemployed and in most instances they await a call from Colombo to do domestic work. This is the ugly side of the discrimination they have faced for years. When we met Seelamma, in Maskeliya who

was hurrying to take her tea break, she only had one request ; “I will retire soon. If you want a maid at home, please give me a call.” We wrote down her number and parted ways.

Sanitation is another glaring issue which has been largely ignored. Women continue to wear cloths instead of sanitary napkins – another indicator of poverty that hasn’t changed over the years. While it is unhygienic, several programmes had been initiated to train women to produce sanitary napkins from cloth which can also be a source of income for them. Underage marriages, single mothers, prostitution, drug and alcohol abuse among youth and domestic violence are other prevailing issues which have more or less spiked over the years in the absence of adequate interventions. When the men involved in drug peddling are put behind bars, their spouses opt for prostitution to earn a living. The Daily Mirror learned that the youth buy three-wheelers once they finish school and because there aren’t many hires they do drug peddling to raise an additional income.

Housing issue

Estate workers have lived in line rooms for years and it has more or less become their lifestyle. But one cannot imagine how they survive inside that 10’12” space; sometimes with their families in them. With hardly any space to

|

Partly constructed houses yet to be given away

|

move inside with a bedroom and a kitchen, the workers have settled in them and their generations have taken over. Once they pass away, the room is vacant for another worker to reside in.

Sometimes these rooms catch fire as they stack firewood in the open ceilings. Since all rooms are built together the fire spreads swiftly. To curb this issue, the Yahapalana regime built 8000 houses, out of which 6000 were given away while 2000 are yet to be given to the people. Out of the 8000, 4000 were built from funds received by the Indian Government. As such, workers in Dimbula, Pathana, Nuwara Eliya and Badulla were beneficiaries. However, the picture remains incomplete in different areas.

In Hatton, the houses to be given away are still under construction. They were given a house on a seven-perch land with no electricity or water and they have to complete the rest of it. It costs around Rs. 400,000 for this. How? Is the question they ask because they earn minimum wages. They also claimed that they weren’t given deeds.

But the situation at Chystlers Farm in Kotagala is different. Around 20 families were relocated in new houses following an initiative by Palani Digambaram and under the Ministry of Hill Country with the aim of building new villages, infrastructure and ensuring community development during the previous regime. These houses were fully completed with water and electricity connections. Apart from that they also have a deed.

Vijayakumar had been living in a makeshift shelter covered in a polythene sheet for the greater part of his life. Now aged 35 he is living in a fully completed house. “I initially supported the CWC, but didn’t receive anything. So I had to shift alliance with unions because I have to raise my family. My wife also works at the estate and we earn a monthly income of around Rs. 25,000,” said Vijayakumar.

However, one of the issues they face is that they cannot give their deed to the bank to obtain a loan since they don’t have individual plans for their houses. The plans were drawn for the entire housing scheme and it would cost around Rs. 5000 to get an individual housing plan done.

Voice of the unions

The unions need money to survive. They have to pay their members and their monthly income is roughly Rs. 1.5 million. But this money is allocated to the union, to pay telephone and other utility bills, go on canvassing, host May day rallies etc.

But what about the people? People were deprived of clean drinking water and were using lamps instead of electricity. Today they have both facilities. People in the estate sector are now state employed. They work as Samurdhi Officers, teachers and at other government offices. The Rs. 1000 allowance was promised before Arumugan Thondaman’s sudden demise. It came about as an agreement between the estate workers and the companies. But to date, it hasn’t been a reality. As an alternative, a decision was made to give small plots of land to these estate workers, so that they become small estate owners. But many other issues emerge as a result. Women will have to put extra effort to maintain these plots of land as the men finish work by 10am. They take to drinks thereafter. Since maintenance was poor, some companies have taken these lands back. These lands are given on a lease. When they work for an estate they get a welfare allowance, EPF and ETF. But when they own their land who will pay them

these allowances?

Apart from that the workers’ expenditure is also high. Almost every house has a cable TV, they use smartphones, the youth buy three-wheelers from parents’ money and so on. By the time they retire they have earned around Rs. 10-15 lakhs. The union members also blame the workers for not being passionate about their profession.

But one would question how else should they be passionate, plucking tea from 8.00am - 4.00pm on hilly slopes, carrying a 16-20 kg weight on their backs, amid leech bites, wasp attacks and threats from leopards?

lives of the majority plantation workers have stagnated for years. According to the 2012 Census, 4.5% of the Sri Lankan population live in estates.

lives of the majority plantation workers have stagnated for years. According to the 2012 Census, 4.5% of the Sri Lankan population live in estates.  Nothing fruitful has happened

Nothing fruitful has happened

age. So I’m paid Rs. 40 per kilo. We can’t find employment in another profession after retirement because we have been plucking tea all our lives. Other than that we can be engaged in babysitting or domestic work. Our husbands too are unemployed and therefore if we are given plots of land to solve the Rs. 1000 issue we would have to double our efforts to maintain them. Our line rooms are dilapidated and during the slightest rain there are leaks all over. If we want a roofing sheet we have to worship politicians. But all this happens while the CWC takes care of us. We are left out of the estate system after we retire, but the CWC is always with the workers,” said Rajeshwari.

age. So I’m paid Rs. 40 per kilo. We can’t find employment in another profession after retirement because we have been plucking tea all our lives. Other than that we can be engaged in babysitting or domestic work. Our husbands too are unemployed and therefore if we are given plots of land to solve the Rs. 1000 issue we would have to double our efforts to maintain them. Our line rooms are dilapidated and during the slightest rain there are leaks all over. If we want a roofing sheet we have to worship politicians. But all this happens while the CWC takes care of us. We are left out of the estate system after we retire, but the CWC is always with the workers,” said Rajeshwari.

was hurrying to take her tea break, she only had one request ; “I will retire soon. If you want a maid at home, please give me a call.” We wrote down her number and parted ways.

was hurrying to take her tea break, she only had one request ; “I will retire soon. If you want a maid at home, please give me a call.” We wrote down her number and parted ways. Vijayakumar had been living in a makeshift shelter covered in a polythene sheet for the greater part of his life. Now aged 35 he is living in a fully completed house. “I initially supported the CWC, but didn’t receive anything. So I had to shift alliance with unions because I have to raise my family. My wife also works at the estate and we earn a monthly income of around Rs. 25,000,” said Vijayakumar.

Vijayakumar had been living in a makeshift shelter covered in a polythene sheet for the greater part of his life. Now aged 35 he is living in a fully completed house. “I initially supported the CWC, but didn’t receive anything. So I had to shift alliance with unions because I have to raise my family. My wife also works at the estate and we earn a monthly income of around Rs. 25,000,” said Vijayakumar.