28 Jan 2019 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

An event, extraordinary by our theatre standards, happened recently. Two plays – Simon Navagaththegama’s Kalu Saha Sudu (Black and White) and Veronica Apasu Ewith (Veronica returns home) were staged on two consecutive days, a Friday and a Saturday. Why is this event extraordinary? Both plays are about South Africa. One is an original play and the other, a translation. Kalu Saha Sudu deals with Apartheid South Africa, its conflict politics, related cruelty and divided loyalties. The play is now produced by Shriyantha Mendis, who plays the leading role of a Police Commissioner aiming to rise to the top at any cost.

An event, extraordinary by our theatre standards, happened recently. Two plays – Simon Navagaththegama’s Kalu Saha Sudu (Black and White) and Veronica Apasu Ewith (Veronica returns home) were staged on two consecutive days, a Friday and a Saturday. Why is this event extraordinary? Both plays are about South Africa. One is an original play and the other, a translation. Kalu Saha Sudu deals with Apartheid South Africa, its conflict politics, related cruelty and divided loyalties. The play is now produced by Shriyantha Mendis, who plays the leading role of a Police Commissioner aiming to rise to the top at any cost.

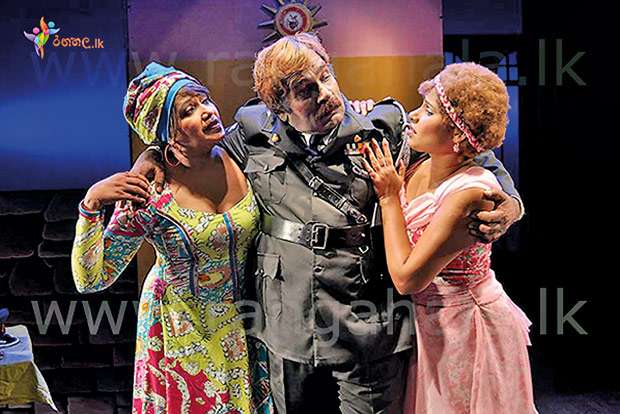

Veronica Apasu Ewith is a translation of Athol Fugard’s Coming Home, which deals with post-apartheid South Africa. It was directed by Budhdhika Damayantha.

Looking back, Simon Navagattegama’s play looks extraordinary because, as far as I know, he has never lived anywhere in Africa. The story is based in Namibia and deals with how South African Police deal with terrorism, or unlawful activities against a State which legally breaks all standards of decency, and was written here when apartheid was at its height.

Relating to the Sri Lankan situation, Simon would have interpreted apartheid in a different light. As for rebellion against the State, the country had been convulsed briefly in 1971, and recovered its full complacency, so that the war in the north and a bigger bloodbath in the south were in the making.

Simon uses melodrama to make his dramatic statements (Recalling the melodramatic choice given to Grusha and the queen in the Caucasian Chalk Circle by Brecht) and makes a colourful and thought-provoking play.

There was a time when our theatre looked outwards when it delighted in staging translations of classic plays, from Brecht, Chekhov, Ibsen to Garcia Lorca and Shakespeare

He even introduces a group of tribal dancers (Who turn out to be Namibian Guerrillas). I don’t know how this would be viewed in Africa today, but it is an effective dramatic device even if the dance didn’t look well rehearsed.

Again, African critics may not react positively to how the black policemen are depicted. But the dramatist is able to unravel their divided loyalties and inner conflicts effectively.

We have a long tradition of drama as a means of protest against dictators and Police States, but Kalu Saha Sudu stands out because it is an original, and that is enough to make him one of our most daring and imaginative writers.

Why is it that the staging of two plays with South African settings extraordinary? Take a look at the context. What we have is a scorched theatre, one dried up of creative ideas. It has also become homophobic to a large extent.

There was a time when our theatre looked outwards when it delighted in staging translations of classic plays, from Brecht, Chekhov, Ibsen to Garcia Lorca and Shakespeare.

Dramatists such as Dayananda Gunawardene even borrowed from Western opera.

But this trend has stalled due to the general cultural crisis faced by our arts. The cinema has recovered a little, in quantity more than in quality, but the theatre is in dire straits. As such, any attempt to stage a translation of a serious play is nothing short of brave.

Buddhika Damayantha is a maverick, who has directed and produced 23 plays till now, starting at age 23, at the rate of almost one per year.

Most of them are translations. He started with Endgame, a play by Samuel Becket, and has staged plays by Tennessee Williams and Harold Pinter, among others. Two years ago, he came up with a translation of Hamlet. This record deserves respect.

Bearded and outspoken, Buddhika along with Rajitha Dissanayake and Dhananjaya Karunaratne (now in Australia) are the best and most experienced exponents the Sinhala theatre has.

It is tempting to call them survivors, but they are more than that. Survivors are helped by circumstances. These two have been creating good theatre while swimming against the current. Buddhika recalls wryly several contemporaries who started in the theatre but chose to migrate to the more lucrative sphere of teledrama and film.

That he isn’t better known for all the hard work is specifically a tragedy of the Sinhala theatre and a tragedy of our culture in general terms.

He lives by the theatre and swears by it, and his Hamlet production shows that nothing is impossible-what most people in a culture drugged by marketing-don’t seem to have noticed.

The trend has stalled due to the general cultural crisis faced by our arts. The cinema has recovered a little, in quantity more than in quality, but the theatre is in dire straits. As such, any attempt to stage a translation of a serious play is nothing short of brave

His favourite playwright is South African Athol Fugard. Veronica Apasu Ewith (Coming Home) is the second part of Valley Song, directed earlier by Buddhika.

But let me go back to Friday. As the Lionel Wendt drew closer, I was thrilled to see two long lines of shiny new vehicles. Has a miracle occurred overnight? This looked like a repetition of Rajith Dissanyake’s audience at this venue last month for his play Hithala Gaththu Theeranayak last month.

It had somehow dawned upon them that Simon’s Kalu Saha Sudu too, was worth seeing. With this transformation, born again audience, the Sinhala theatre too, would be reborn.

Hell knows no fury like a man whose illusions crumble into dust as soon as they are born. The shining vehicles were there for a tamasha next door.

The play’s audience numbered less than 100. There were more people there for Buddhika’s play at the Punchi Theatre on Saturday.

But they looked snug inside the smaller space, and the set was a pleasure to behold when the curtain opened.

Veronica returns from her shattered dream of making it as a singer in the big city to a tiny one-room house. The set as designed by the dramatist looks every bit authentic.

Buddhika considers the set to be a character. In pale greens and browns, with the grandfather’s cup and other utensils waiting like neglected family, it certainly has character. There’s a compelling sadness about it.

Simon’s play was about people destroyed by political ideology and resulting violence.

Athol Fugard writes about a different kind of destruction – of self, brought about by fateful decisions, bad luck and circumstances.

It has much to say about Sri Lanka, but there is only a select band of listeners – the dramatist’s faithful audience, an enlightened inner circle making their own peace with a vulgar and wayward society

It is both sweet and sadly nostalgic. Its three main characters – the ebullient Veronica Jonkers, whose dreams of big-time are shattered by circumstances, and the contraction of AIDS, and her loyal childhood friend Alfred (Steve), poor, well-meaning but not very intelligent, and her late grandfather Oupa, now a benign ghost – are played ably by Ferny Roshni (Veronica), Jayantha Bandara (Steve) Chandrasoma Binduhewa (the grandfather) with Veronica’s son played by two child actors (Dehemi Agbo and Tharanga Kulatunga) as a very small boy and then as a teenager.

The play starts slowly, building up the dramatic force at an unhurried pace until the climactic moment when Veronica tells Alfred that she would like to marry him for the sake of her fatherless son Mannetjie. The conflict between Alfred and Mannetjie heightens, but the two make peace. This is a story about inner peace and making peace with yourself, and with a harsh, uncaring world.

It has much to say about Sri Lanka, but there is only a select band of listeners – the dramatist’s faithful audience, an enlightened inner circle making their own peace with a vulgar and wayward society.

30 Nov 2024 23 minute ago

30 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 5 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 6 hours ago

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024