12 Mar 2019 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Evangelical revival that spread its wings in late 18th century and early 19th century England was initially centred at Cambridge University. The Cambridge group was later to be supplemented by another organisation known as the “Clapham Sect”, which in many ways was more influential: its leader, William Wilberforce, was leader of the Abolitionist Movement. These two groups would pioneer many of the methods of evangelism, to be resorted to later on in the colonies.

By this time, Christianity was on the way to becoming a “world religion”, which in Weber’s formulation meant that it had the mechanisms through which it could gather “multitudes of confessors” around it. Lacking all those mechanisms, Buddhism faced a crisis: it lost its position as a State religion.

The attitude of the missionaries and the colonial officials was one of optimism and idealism: one administrator remarked in 1840 that he anticipated Buddhism, “shorn of its splendour, unaided by authority”, to “fall into disuse”, while James de Alwis argued that “[t]here are good grounds for believing that Buddhism will... disappear from this Island.”

Ironically, however, certain sections of the Ceylonese and Western intelligentsia contributed to the eventual reversal of this state of decline. We can mention two of these here: the Orientalists and the Theosophists. The former were to be found among those who, despite the official shift to English education in the 1830s and the 1840s, continued to study Sinhala, Pali, and Sanskrit literature and took part in debates over the intricacies of these languages; the latter came in the late 19th century as a result of a series of famous encounters between missionaries and monks.

It is not uncommon to come across otherwise dogmatic, bigoted, and anti-Buddhist propagandists such as de Alwis writing, and speaking, on Sinhala and even Buddhist literature with enthusiasm. De Alwis had acquired knowledge of Sinhalese, Pali, and Sanskrit under a former monk, Batuvantudawe Devaraksita; he would later take part in one of the most famous linguistic debates in post-1815 Sri Lanka, the Sav Sat Dam Vadaya, and translate the Sidat Sangarava, the latter being the only historical sketch written in English by a Sinhalese in British Ceylon.

However, despite this wave of enthusiasm among the Christian elite, Sinhala and Buddhist literature remained in the pirivenas. Officials viewed these schools, not with disapproval, but with disdain: “the education afforded by the native priesthood in their temples and colleges scarcely merits any notice,” Colebrooke would note. The process of capitulation and disestablishment in the Buddhist clergy was thus most acutely felt in the realm of education, which had to do with the alienation of temple lands and the draining of monastic wealth resulting from the enforcement of Ordinance No. 10 of 1856. Shorn of its prestige, Buddhist temples, especially in the hill country, took a heavy toll from the government cutting off all links with them.

However, despite this wave of enthusiasm among the Christian elite, Sinhala and Buddhist literature remained in the pirivenas. Officials viewed these schools, not with disapproval, but with disdain: “the education afforded by the native priesthood in their temples and colleges scarcely merits any notice,” Colebrooke would note. The process of capitulation and disestablishment in the Buddhist clergy was thus most acutely felt in the realm of education, which had to do with the alienation of temple lands and the draining of monastic wealth resulting from the enforcement of Ordinance No. 10 of 1856. Shorn of its prestige, Buddhist temples, especially in the hill country, took a heavy toll from the government cutting off all links with them.

If the three pillars of colonialism in the British era were Christianisation, “bourgeoisification”, and Western education, then the three pillars of missionary work were preaching, the press, and education; education, for obvious reason, figured in both. The pirivenas suffered on this count when attempts were made in the 1850s and 1860s by the heads of these institutions to turn them into formal colleges; the monks lacked the experience to maintain registers, ensure attendance, and adhere to the other requirements set down by the Department of Public Instruction.

We get an idea of how “archaic” the teaching methods of the monks were regarded as from a comment by the Director of the Department, H. W. Green: “they prefer to follow their old-fashioned methods of instruction in learning by heart passages of the sacred Buddhist books, and in acquiring a small amount of astrology and medicinal knowledge.” The monks, in other words, could not impart any knowledge that could be called “modern”; the place of renown that in ancient Sri Lankan society had been given to “bahussuttas”, or intellectuals capable of astonishing feats of memory, was very naturally not considered in the British era.

Curiously enough, the absence of government patronage, which had destroyed the larger monasteries in the Kandyan regions, became a source of impetus for the smaller monasteries in the littoral regions. The British brought their schools here, but not their Universities; the first such institutions to be built were started by Buddhist monks in these regions: the Vidyodaya Pirivena by Hikkaduwe Sumangala Thera in 1873 and the Vidyalankara Pirivena by Ratmalane Dharmaloka Thera in 1875.

But it remains one of the more enduring legacies of these institutions that, even at their inception, the curriculum they developed was far away from the parameters of “useful knowledge.” They did not teach mathematics and algebra, and the monks were castigated for not evincing interest in these subjects. On the other hand, it is wrong to think that the issue was limited to monastic institutions, since officials lamented the absence of useful subjects in English schools as well.

While the monastic schools laid an emphasis on Sinhala, Pali, and astrology, the elite schools laid an emphasis on Latin, Greek, and Hebrew at the cost of mathematics; by 1845 for instance, algebra at the Colombo Academy “did not go beyond quadratic equations”, while when the Turnour Prize for Classical and English Literature was started the following year, “a considerable number of students” vied for it, as opposed to the Mathematics Prize that “attracted only three students.” The absenting of science and mathematics from the public school curricula would be faulted by the historian Eric Hobsbawm for the later decline in Britain’s industrial strength.

"The Buddhist revival had paradoxically sown the seeds of its own transformation, from a largely monastic body to a

mostly secular movement"

As with the school and college, so with the printing press. One of the earliest works of literature written by the Sinhalese people was the Tripitakaya, which until the Fourth Buddhist Council at Aluvihara in Matale, during the reign of Valagamba, had been committed to memory. No real written tradition had flourished until then among the Buddhist clergy, who, as Walpola Rahula Thera pointed out, took “into their hands the education of the whole nation.” But even after the writing down of the Buddhist tracts, literature was limited to the (libraries of the) monasteries; ola leaves were in any case “not in extensive use, like the printed books of today.”

It was thus only to be expected that when the Dutch established the first Sinhalese printing press in 1736 and when the Wesleyan missionaries followed suit in 1815, they gained a virtual monopoly over the printed word, a privilege that the Buddhist monks would not avail themselves of until much later.

While the Dutch had used their Press to disseminate the teachings of Christ among the masses, the British, as Kitsiri Malalgoda has  noted, used them “for much wider ends.” These wider ends included a sustained, uninterrupted flow of anti-Buddhist tracts, which in the hands of two zealous missionaries, Spence Hardy and Daniel Gogerly, spread the idea of the disestablishment of Buddhism “from the Island.”

noted, used them “for much wider ends.” These wider ends included a sustained, uninterrupted flow of anti-Buddhist tracts, which in the hands of two zealous missionaries, Spence Hardy and Daniel Gogerly, spread the idea of the disestablishment of Buddhism “from the Island.”

The Buddhists rallied a response: they established their own presses. Ironically though, they had to rely on the missionaries, since the first Buddhist press in Colombo was the same press that had been used by the Church Missionaries in Kotte. Added to this was another paradox: while the Buddhist laity, particularly the urban middle class and petty bourgeois sections, felt the need to counter the onslaught of Christian attacks on their religion, the more conservative sections expressed discontent with the way the role of the laity was being widened. This was seen in the responses to the proposal for the construction of a press in Galle in 1865: “not many Buddhists were convinced of the ‘merits’ of helping to establish a Buddhist press.”

It was the same trend one infers in the response of Buddhist leaders in education; as with the press, there too they had to widen the role of the laity. What scholars have referred to as Protestant Buddhism was here shaped by Westernisation; the Buddhist response, in other words, was fuelled by various “isms” rooted in Western ideology: occultism, rationalism, cosmopolitanism.

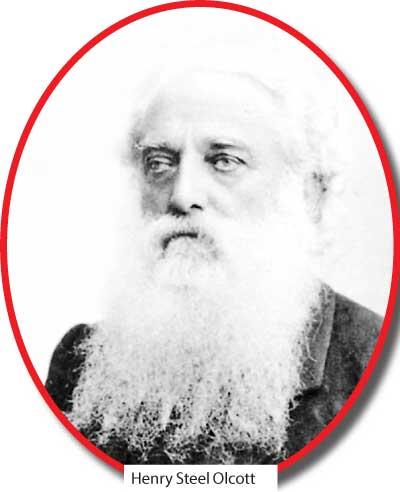

The disagreements between the old heads of the revival (Migetuwatte Gunananda Thera and Anagarika Dharmapala) and the new Theosophist leaders (Henry Olcott, Helena Blavatsky, and Annie Besant) were in that sense inevitable. The Buddhist revival had paradoxically sown the seeds of its own transformation, from a largely monastic body to a mostly secular movement. In other words, there was a triumph on the one hand, and on the other, defeat as well.

30 Nov 2024 49 minute ago

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024