09 Jun 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Another argument is that by laying snares, apex predators such as the leopard will be deprived of its food

Another argument is that by laying snares, apex predators such as the leopard will be deprived of its food

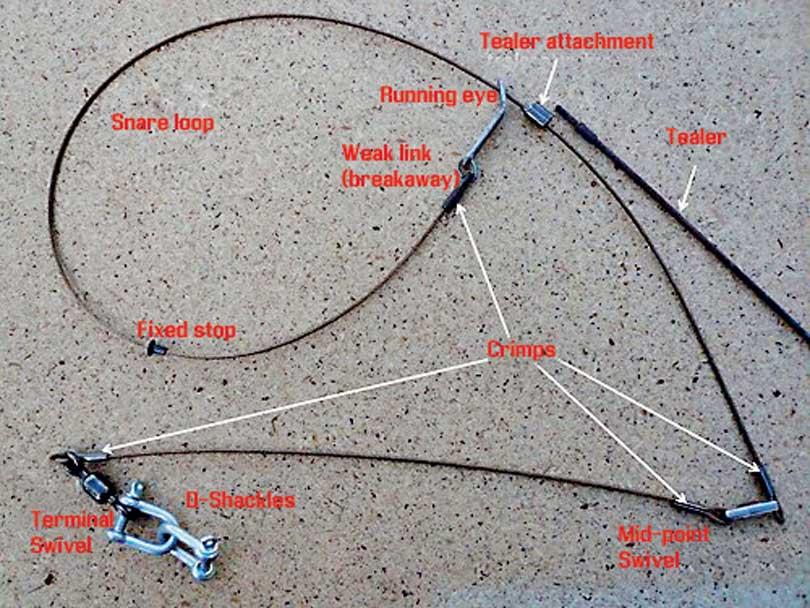

While the cause of death of the black leopard is yet to be known, conservationists raise concerns over lapses in enforcing the law on those who lay snares and traps. It is a known fact that people in the plantation sector lay snares and traps to protect their vegetable plots from animals such as pigs and wild boar. The trapped animals, when killed and sold for meat, in turn put some extra bucks on the table. However, a large number of leopards have been trapped in these snares and the practice seems to continue as the estate management and law enforcement authorities continue to turn a blind eye to the issue.

While the cause of death of the black leopard is yet to be known, conservationists raise concerns over lapses in enforcing the law on those who lay snares and traps. It is a known fact that people in the plantation sector lay snares and traps to protect their vegetable plots from animals such as pigs and wild boar. The trapped animals, when killed and sold for meat, in turn put some extra bucks on the table. However, a large number of leopards have been trapped in these snares and the practice seems to continue as the estate management and law enforcement authorities continue to turn a blind eye to the issue.

Hence, the Daily Mirror sheds light on the repercussions in not following existing protocols, lapses in law enforcement and the relationship between snares and bushmeat.

Protocols ignored ?

There was speculation that the veterinary team delayed to reach the location where the black leopard was snared. One of the accounts claimed that the delay was long as eight hours. When inquired into, Dr. Tharaka Prasad, Director- Wildlife Health at the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) said that there had been no delays. “I got the first call at 11.15am on May 26th by one of the doctors at DWC. Following that the DWC Director General called me at 11.19am and asked to deploy a team to the location. At 11.56 am I called Dr. Malaka who was at Koslanda and asked him to attend to the matter. He had reached the location from Udawalawa by about 3.00pm. By the time they reached the place they had realised that the noose was around its neck and people too had started gathering to film the incident. The team had to keep it until 7.00pm because after being anesthetised the animal usually gets a high temperature. They had tried taking it to an STF camp nearby and had even kept it near the jungle area, but they weren’t confident enough to release it. The doctors said the blood supply had stopped. After informing the DG they got orders to monitor its condition for a day and thereafter it was slowly taken to Udawalawa Elephant Transit Home. By the time they reached it had been around 1.00am. The following day I too went there. We noticed an inflammation in the place where it had the wound and the doctors were giving painkillers, antibiotics, food and water. However it died on May 27th morning,” said Dr.Prasad.

Talking about practical challenges during a rescue Ashan Thudugala, wildlife conservationist and co-founder at Small Cat Advocacy and Research (SCAR) said that wild cats are curious and shy creatures in nature and they always try to stay away from human eyes. “What happens when they are snared and caught is that these cats get surrounded by waves of people. This makes the cat even more stressed and they try to run away from the place and jump about. This sudden activity causes the snare to tighten with each movement. Snaring causes huge pressure on certain parts of the body and it decrease the blood supply to the main organs and tissues which can lead to organ malfunction and eventually death. Therefore some of the practical issues include reaching the location of the snared cat as soon as possible, crowd control and study the internal damage caused due to snaring.” said Thudugala.

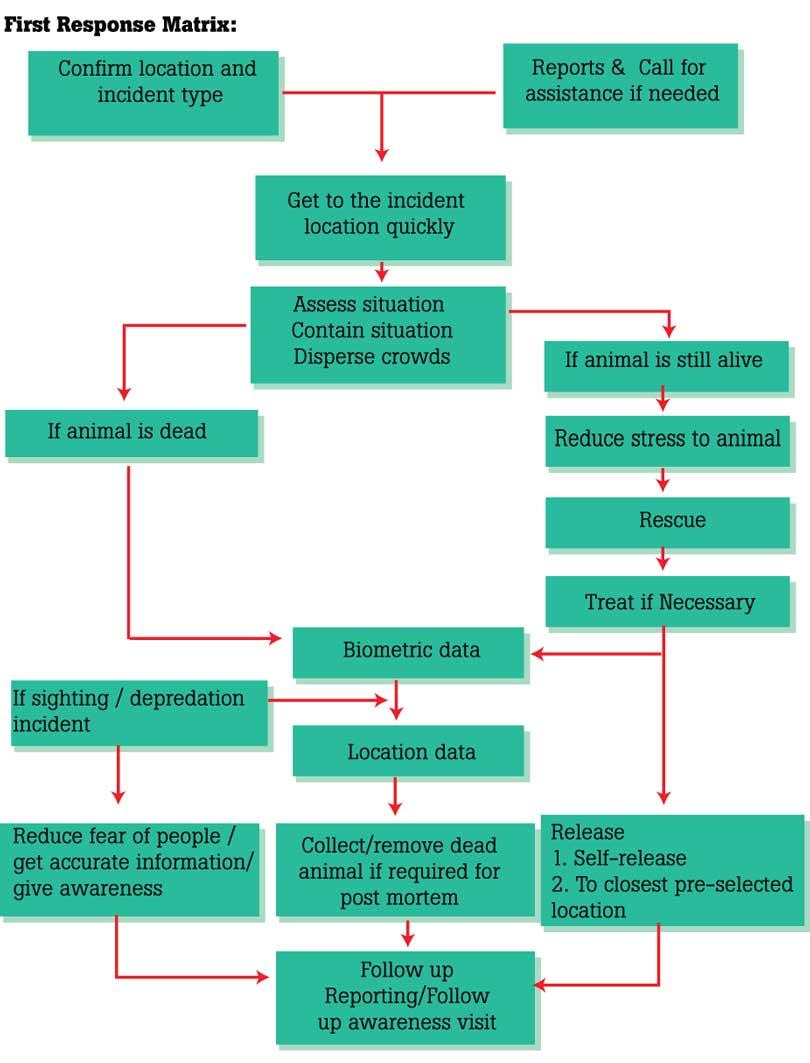

However a manual titled Protocol Manual Guidelines for Human-Leopard Incident Management already exists and sheds light on how an animal caught to a wire snare or a leopard that has fallen into a well or pit should be rescued. One of the most important guidelines is to disperse crowds during a rescue which is seldom seen in most instances. It also gives insights on different events such as during a leopard attack on humans and livestock and what needs to be done if a leopard or wildcat is sighted.

Killing a barking deer, sambar or species such as pangolin are non-bailable offenses under Section 30, subsection 2

Jagath Gunawardena

Legal provisions in place

Snares are laid in vegetable plots run by workers in tea estates. Therefore they are laid outside protected areas. In fact the law is quite clear, but there exists a lack in enforcement and implementation. Hence, the legal provisions are as follows :

Section 30 : The use of traps, snares or other instruments to kill, wound or take any wild animal is prohibited outside a National Reserve or sanctuary.

Section 30 (1) : Any person who uses traps, snares or other instruments to kill, wound or take any wild animal (in Schedule I) outside a National Reserve or sanctuary is guilty of an offense and on conviction be liable to a fine not less than Rs. 20,000 and not more than Rs. 50,000 or to imprisonment of either description for a term not less than two years and not more than 5 years to both such fine and imprisonment.

Similar provisions exist for those found guilty of laying snares and traps within nature reserves and protected areas. According to Environmental Foundation Ltd., both the DWC and the Police have enforcement powers. There are different fines depending on the animal and the places in which the snares and traps are set. “We have gotten hold of many perpetrators but it would be best if people also could inform us about any wildlife crime that they come across,” requested DWC Director General, M.G.C Sooriyabandara. “We have set up a hotline (1992) for this purpose and therefore we can maintain the records and follow these incidents. People also need to act responsibly. We need the support of grama niladharis and estate managements to find out who lays these snares and traps. There’s no point in conducting educational programmes for people if they are not ready for change. More than 50 leopards have been trapped in snares in the Central province despite having awareness programmes for the past 10 years,” said Sooriyabandara.

Snares and bushmeat

The Daily Mirror also learned that during the curfew most plantation workers were able to earn extra income by selling bushmeat. This source of income existed through the sale of bushmeat to hotels and restaurants and providing the meat as bite for those addicted to moonshine. Hence, one kilo of wild boar meat would be priced between Rs. 650-750. Back in 2018 killing wild boar was legalised. “But the sale of wild boar meat is prohibited,” opined environmental lawyer Jagath Gunawardena. “It’s a cognizable offense where a person found guilty could be arrested without a warrant, but it’s bailable offense as well. Some of the frequently killed species for bushmeat include spotted deer, sambar, wild boar and barking deer (olu muwa). But killing a barking deer, sambar or species such as pangolin are non-bailable offenses under Section 30, subsection 2,” said Gunawardena.

From his observations, Thudugala said that the community has to play a major role regarding this issue. “Since most of the snares are placed to capture wild boar and other small mammals it has to be controlled within the society. What we can do is form a group of volunteers in most affected areas and conduct search patrols along animal pathways. It would be more effective if these people can be equipped with metal detectors or other equipment which help to detect snares. Another thing we can do is promote and initiate small scale live stock farming with proper caging facilities in these villages especially targeting low income families. This will reduce people going after bushmeat or consuming or selling it. But this has to be managed properly since more livestock can also attract the carnivores and without proper cages this can increase the human-wild cat conflict. Reducing and taking action against bushmeat is another concern and we also have to raise awareness about laws and the importance of wildlife at community level. A rewarding system for providing information can encourage the people to provide information and control bushmeat hunting,” said Thudugala.

The market is largely Sri Lankan travelers who visit these wilderness areas, who enjoy the beauty and wildlife and then seek bush meat for dinner

Dr. Sumith Pilapitiya

Another argument is that by laying snares, apex predators such as the leopard will be deprived of its food. Responding to this, Thudugala further said that wild animals tend to move towards low energy and high gain food or prey items and cats love easy and fast food. “If bushmeat hunting is increased it would also reduce the number of potential prey for carnivores. This can also encourage carnivores to move in to human settlements to look for prey and this phenomena could increase the human wildlife conflict,” he warned.

However, when contacted, Officer-in-charge at Nallathanniya Police Station Laksiri Fernando denied claims of bushmeat being sold at hotels and restaurants. “During the curfew all these businesses were closed. Since laying snares and traps is illegal we have educated the people and have arrested a few people who had placed these traps. People mainly lay them to protect their vegetable plots,” Fernando said. During the curfew period DWC officials found bushmeat during raids conducted in Thalawakele, Randenigala, Athimale and Katagamuwa.

Zoonotic diseases

“One of the most inhumane forms of poaching is snaring,” opined Dr. Sumith Pilapitiya, conservationist and former Director General at DWC. “Snares are laid mainly for two purposes. One is for capturing wildlife for bush meat. The other reason is to capture wild animals that may damage crops. Regardless of these reasons, snaring puts an animal through agony. When it struggles to escape from the snare such movements generally cause internal injuries which could be fatal,” affirmed Pilapitiya.

He further said that although snares are not really laid for leopards, they are the unintended victims. “According to available data, around 48 leopards have died due to snares during the past 10 years. This exemplifies the gravity of the problem with snares. But the real reason for snares is to capture other wildlife such as deer, sambar and wild boar that have been caught in snares by their hundreds over this period, without drawing public or media attention. Snaring is a very serious threat to wildlife. The laws should be strengthened, so that poachers would receive the just punishment. But for this to work out, local politicians should stop providing protection to their supporters who are engaged in poaching. There have been numerous instances where political patronage has prevented the DWC from prosecuting poachers. But we must realise that the larger market for bushmeat is not associated with the local poverty stricken villagers surrounding protected areas and other forests. The market is largely Sri Lankan travelers who visit these wilderness areas, who enjoy the beauty and wildlife and then seek bush meat for dinner. If we are to stop poaching, we need to eliminate the market for bushmeat. An ongoing programme of awareness on the perils of snaring is a must to educate the public to reduce the demand for bushmeat. COVID 19 is a zoonotic disease—which means the virus moved from animal hosts to human hosts. While COVID 19 originated in China, zoonotic diseases can emerge anywhere in the world that has the opportunity for an animal virus to move to a human host. The easiest way for this to happen in Sri Lanka is through consumption of bushmeat. So as long as people consume bush meat, they are vulnerable to a zoonotic disease. I think this is the strongest argument against bushmeat consumption,” explained Dr. Pilapitiya.

Large crowds gathered during rescue of the black leopard

Bushmeat (Sambar deer) found during a raid at Randenigala-Rantambe sanctuary (DWC)

Root causes and solutions

According to Anya Ratnayaka, wildlife biologist and SCAR co-founder, in Sri Lanka, the leopard, fishing cat and the rusty-spotted cat are all classified as Endangered under the National Red List 2012 of Sri Lanka. “This means that their populations are at a high risk of going extinct in the wild. The jungle cat is classified as Near Threatened (National Red List 2012 of Sri Lanka) , so their population is at risk of becoming endangered in the near future,” said Ratnayaka.

She further said that people in low income settlements know much more about the dangers in laying traps, snares, gun traps, hakka patas and whatever other method used to capture and kill wildlife, far better than outsiders do. “They know how these snares and traps etc., work and the pain it would inflict. They know what the repercussions are if they get caught, and yet they continue to do it. They also know what human-wildlife conflict is, first hand. It’s something that many of us can only imagine, and it’s very easy for us to judge from the comfort of our homes,” said Ratnayaka.

Human-wildlife conflict mainly affects low income communities. They lose crops, live stock and in some cases, family members to wildlife.

Anya Ratnayaka

In response to a question raised on how leopards and small cats could be protected she said that all the studies in the world can be done on the wildlife we have in this country, using the most sophisticated technology out there and added, “But nothing will change if we don’t address the underlying issues that cause human-wildlife conflict. Human-wildlife conflict mainly affects low income communities. They lose crops, live stock and in some cases, family members to wildlife. They set snares and traps to capture wildlife to feed their families - either by consuming it themselves, or selling the meat.

“We as citizens of Sri Lanka need to stop blaming the Department of Wildlife Conservation for everything. They are already stretched thin on resources and personnel. Even if we provide them with the most sophisticated tools, provide them with funds to treat snared animals, and hire an army of new rangers, poaching would still continue. Why? Because we will only be treating the symptom, and not the actual disease. We need to find solutions to help low income communities find alternate ways to provide food for their families. Whether it be by helping them protect their crops more efficiently, or fighting to raise their daily wages, so that they could afford to feed and clothe their families.

“We must also remember that the wild boar eaten during family trips made to national parks and estates on those long weekends that we so look forward to, was caught in a snare. And how many other animals were caught in that snare before the one on your plate?” she queried.

Pix by Gamini Bandara Ilangathilaka

28 Nov 2024 12 minute ago

28 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 4 hours ago