16 Jun 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Examining old problems and new trends in child labour in Sri Lanka

According to 2016 data 22.6% of children are involved in services and sales related jobs.

Pic by Kushan Pathiraja

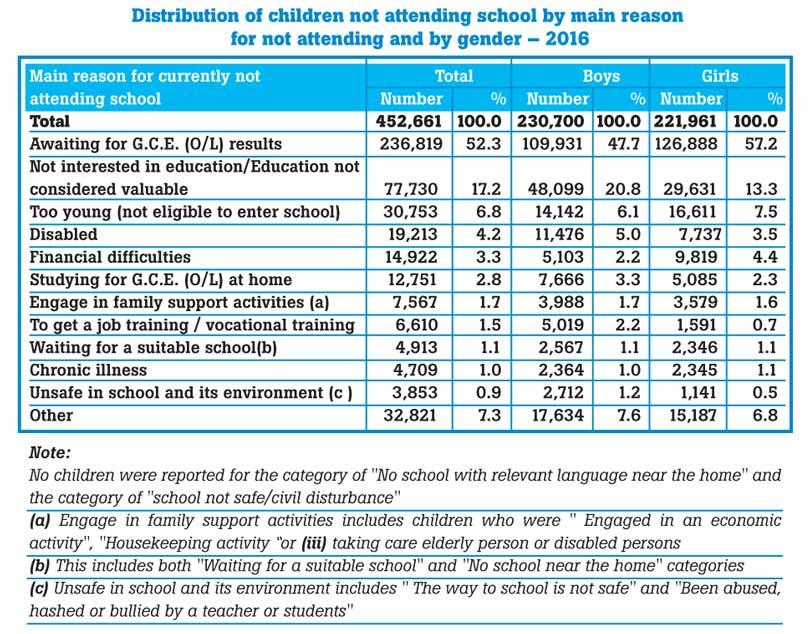

According to the latest Child Activity Survey conducted by the Department of Census and Statistics in 2016, out of the 4,571,442 child population, a total 452,661 children were not attending school. The report lists out over 16 different reasons as to why children don’t attend school. One of the main reasons included a lack of interest, or the perception that education was not valuable. Other reasons included disabilities, chronic illnesses, unsafe environments to travel to school, and financial difficulties among others.

According to the latest Child Activity Survey conducted by the Department of Census and Statistics in 2016, out of the 4,571,442 child population, a total 452,661 children were not attending school. The report lists out over 16 different reasons as to why children don’t attend school. One of the main reasons included a lack of interest, or the perception that education was not valuable. Other reasons included disabilities, chronic illnesses, unsafe environments to travel to school, and financial difficulties among others.

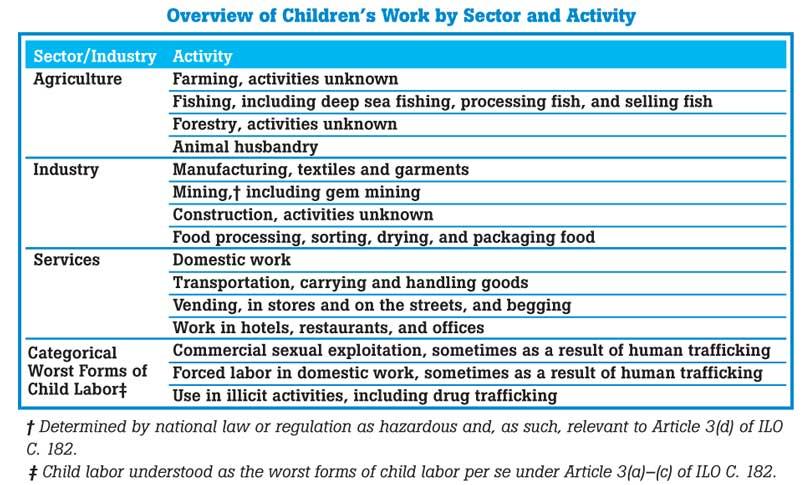

Child labour is largely divided into three sectors, namely, agriculture, industry and services. In Sri Lanka, although there are reports on child trafficking and exploitation of girls for sex work, there has been little to no evidence to prove such practices exist. Several law enforcement authorities including the National Child Protection Authority and the Department of Labour have the authority to intervene and inquire into cases of violations of legal provisions pertaining to the employment of children.

Daily Mirror followed the progress made in terms of child labour, and found out what more needed to be done to strengthen existing laws.

Child Activity Survey 2016

The survey which was conducted covering all 25 districts reports that almost 40% of children between the ages 5-17 were not attending school. Of the total, 51,249 had never attended school in their life. Another 401,412 children had previously attended school (see graphic). The survey also indicated that more boys than girls were involved in economic activities. According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), Hazardous Child Labour (HCL) represents the largest category of children working in the worst forms of child labour. This occurs in sectors as diverse as agriculture, construction, mining, manufacturing, fisheries, service industries and domestic service. The survey further revealed that 42.2% of children were engaged in elementary occupations including construction work, crop farm labourers, as cleaners and helpers in offices and other establishments, hand packers, fishery and aquaculture labourers and so on. Additionally, 22.6% were involved in services and sales related jobs. From the total child population, 39,007 children have been involved in hazardous forms of child labour. The survey revealed in 58% of hazardous forms of child labour the ‘number of hours worked is greater than 43’ out of which 31,361 children in HCL were from rural areas.

Many ‘soon-to-be young adults’ engaged in child labour: ILO Country Director

Over the years, the ILO, in line with its normative framework on child labour standards and recommendations, has supported governments, workers and employers, and many others to pursue a multi-pronged approach to preventing and responding to child labour. With this in mind, the Daily Mirror spoke to ILO Country Director Simrin Singh to find out newer challenges pertaining to child labour in Sri Lanka.

Over the years, the ILO, in line with its normative framework on child labour standards and recommendations, has supported governments, workers and employers, and many others to pursue a multi-pronged approach to preventing and responding to child labour. With this in mind, the Daily Mirror spoke to ILO Country Director Simrin Singh to find out newer challenges pertaining to child labour in Sri Lanka.

Excerpts:

QHow has the existing pandemic affected child labour in the country? Do you observe a spike or decline?

QHow has the existing pandemic affected child labour in the country? Do you observe a spike or decline?

There are presently no COVID-19 related survey data on which to base a call on whether child labour has spiked or declined, understandably so under the current circumstances with its challenges in terms of data capture methodologies. Under the present extraordinary circumstances with schools closed and certain parts of the country facing restricted movements, it is difficult to gauge the real impact on child labour trends, much less conduct surveys as traditionally done.

However, based on global experience over the years from other emergency situations, one cannot discount a real likelihood the pandemic could be triggering an increase in child labour. The pandemic has already caused known economic damage, disruption to family livelihoods, with economic recovery anticipated to be slugging in the months ahead. Major economic sectors that have employed so many, like tourism and hospitality, construction, agriculture, and apparel, have experienced economic shocks with the incomes of adults employed in these sectors significantly compromised. Those families, who were prior to COVID-19 surviving just above the poverty line, may very likely find themselves now trapped in poverty and thus revert to any means for survival—including using the labour of children to supplement lost incomes, given the dire circumstances.

QWhat are the newest forms of child labour that have been identified?

The issue here to focus on is that existing categories of child labour could take new dimensions, given the lack of income security and exacerbation of vulnerabilities for so many families in so many sectors of the economy that may have already been living on the edge prior to the pandemic. One area to be very vigilant about is the use of information technology to exploit children. For instance, these days many children have access to mobile phones and the internet, increasing their risk of exposure to online and virtual commercial sexual exploitation.

QAccording to the 2016 Child Labour Survey, children working less than 15 hours per week and children engaged in agriculture haven’t been included as child labourers. Why is this?

The survey methodology followed robustly negotiated and agreed upon international standards on capturing child labour statistics as manifest in the 20th Resolution of the International Conference of Labour Statisticians. These in turn are aligned with ILO standards governing the minimum age for entry to employment (ILO Convention No 138) and the elimination of the worst forms of child labour (ILO Convention No 182). The maximum number of working hours coupled with factors such as non-interference with schooling by age group, and absence of hazards to children while working amongst others, are factors in statistically determining incidence of child labour.

QSeveral criminal law enforcement officials were trained to prevent worst forms of child labour. Do you see any progress with the training given, especially in their engagement to prevent child labour?

Indeed, law enforcement officials play a critical role in responding to child labour violations. But they also—together with many others—play a critical role in preventing child labour. Prevention is so essential. As such, it is not only criminal law enforcement officers, but also child protection actors, such as the district-level Labour Officer, the Probation Officer and Child Rights Promoting Officers, who play such a crucial role in preventing child labour. The ILO, together with the Department of Labour, has over the years invested heavily in enhancing the knowledge of a large cross-section of local actors to identify and to effectively respond to cases of child labour, beyond just a criminal law enforcement response.

These training sessions have increased clarity and focus in case identification, improved early detection and enhanced coordination for tailored responses for children at risk of child labour, and those unfortunately in child labour and their caregivers.

QWhat’s the situation in the North and towards the country’s interior, such as children in the estate sector?

Child labour incidence in the country mirrors where economic activity is more intensified—often in semi-urban areas where trades and services, including those in the informal sector, account for a large proportion of the employment. Child labour incidence in agriculture is not as significant as that in the trades and services sectors in Sri Lanka. Child labour and non-attendance in regular schooling is relatively higher in Sri Lanka’s rapidly urbanising city centres than in rural areas. There is an established pattern of child labour—predominantly in the teenage category, engaged in the informal services sector. Their numbers are highest in the districts of Kurunegala, Gampaha, Colombo, Monaragala and Batticaloa, with many other urbanised localities not far behind.

A large proportion of soon-to-be young adults are engaged in child labour within the broader ecosystem of the informal services sector: such as tourism, transport, petty trading, and care giving. A majority of these children are boys. A large number also work in boutiques, tea kiosks, eateries, and other informal trades, in low-wage and precarious employment.

QWhat legal improvements can be made to strictly enforce child labour laws and bring employers, human traffickers and other offenders to justice?

The Sri Lankan legal framework to prevent child labour protects those being exploited in child labour, and to prosecute those violating child labour laws is relatively robust and aligned to ILO Standards. There are still some gaps however, which are fortunately at an advanced stage of being filled. These include closing the current gap in terms of minimum age of employment (presently 14) and age of completion of compulsory schooling age (16 years). Further, updated categories of hazardous child labour have been identified following significant multi-stakeholder consultation and research, and is at the cusp of regulatory authority approval.

Child-friendly system needed

Explaining the background to the enforcement of child labour laws in the country, lawyer and Founder/Director of the Child Protection Force (CPF) Milani Salpitikorala spoke about the Employment of Women, Young Persons and Children Act of Sri Lanka (1956). “This Act—amended in 2006—interprets that a ‘child’ is ‘a person who is under the age of 14 years’. This is to say that it is under the legal purview of this act that a person over the age of fourteen (14) can be employed. However, the act also states that ‘night working’ is prohibited until the age of maturity which is 18.”

“The Children and Young Persons Ordinance of 1956, an Act that concentrates on the Care and Protection of Children and Young Persons states that the Act is available for persons under the age of sixteen (16). The Sri Lankan law has a disparity between the ages that define a ‘child’. However as per international standards according to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child a ‘child’ is someone below the age of 18. The fact that our laws don’t define a ‘child’ is itself a huge loophole, not only for labour laws but for all laws and systems concerning children.” A study by ILO revealed that Sri Lanka lacked a labour inspection policy. Salpitikorala added the study is probably correct, as CPF has received many complaints of young children working in extremely difficult situations in the main cities around the country.

“There is also a big concern regarding care-leavers (children who have left child-care institutions) who are sent for work by the age of 16. These children get exploited labour-wise and person-wise. No one follows up on their well-being although the relevant government departments have a mandate to do so. There are known cases of some of them thereafter getting addicted to drugs or going into sex work. Another major concern is their National Identity Cards mention the address as the particular probation home they were raised in. This is a problem at the point of employment, and employers are reluctant to employ such children and young persons.” When asked about progress in bringing perpetrators to justice, Salpitikorala said there are certain laws in place. “However once it comes into contact with the police and thereafter the justice system, matters tend to be delayed and take their own turn, and are sometimes even exploited for personal gains.”

In the event a child is rescued from sexual exploitation or trafficking, usually an attempt will be made to find the guardian of the child. “If no guardian is found, the police will then file a court case and the courts may order the child to be placed in a care home. Care homes and institutions are governed under the Department of Probation and Child Care Services.

The child then goes through the justice system where much secondary victimisation would occur. With no offence to the current system, we could undoubtedly say that our system is anything but child-friendly. But it could definitely be improved by a more holistic child-centred system where the child (victim or offender) is the centre of the system and every person who is an actor to the system works towards the best interest of the child as per standards of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, to which Sri Lanka became a signatory in 1991.”

The fact that our laws don’t define a ‘child’ is itself a huge loophole, not only for labour laws but for all laws and systems concerning children

28 Nov 2024 5 minute ago

28 Nov 2024 13 minute ago

28 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 4 hours ago