11 Apr 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Suba Seth Gedara

Pic by Michael Meyler

“Beginnings are always arduous; venturing into the unknown needs enormous courage.”

From ‘Reflections on the Diaries of Father Michael Rodrigo’

Never again will Sri Lankans observe Easter Sunday without a twinge in our hearts. Last year, when the attacks on churches shook us to our core, we could not have imagined that an even greater horror was waiting in the wings. This year, as we enter our third week of lockdown—a first even for a population accustomed to curfews—there will be no egg hunts, no services, no singing. Only a sombre reflection of the state of a world brought to its knees by a microscopic pathogen that has claimed more than 50,000 lives in just three months.

Never again will Sri Lankans observe Easter Sunday without a twinge in our hearts. Last year, when the attacks on churches shook us to our core, we could not have imagined that an even greater horror was waiting in the wings. This year, as we enter our third week of lockdown—a first even for a population accustomed to curfews—there will be no egg hunts, no services, no singing. Only a sombre reflection of the state of a world brought to its knees by a microscopic pathogen that has claimed more than 50,000 lives in just three months.

The Covid-19 pandemic has covered the earth in a terrible silence, and we find ourselves staring into a black hole of uncertainty. But even as we shut our doors, we cannot fail to notice the open window: an unprecedented opportunity to frankly and honestly assess the human condition, and determine how we will move forward. Will we return to the rat race or will there—could there—be a kind of rising? A rebirth? The latter would require a lot—nothing short of abandoning our old way of life.

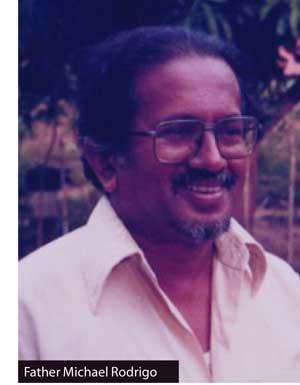

Just over 30 years ago, a small group of people made the decision to do just that. Turning their backs on the comforts of their homes, the embrace of their families, even the possibility of wealth and professional advancement; they set out for the poorest village in the poorest district of the poorest province of Sri Lanka. The village was called Alukalawita, located in the district of Moneragala, close to the town of Buttala in the Uva Province. Led by a Catholic priest named Father Michael Rodrigo, this cohort of sisters and lay people acquired a small plot of land with a simple, thatched-roof hut which became the nucleus of a unique and radical poverty-alleviation campaign.

Their dwelling place was known as ‘Suba Seth Gedera’ and all who passed through it abided by one simple gospel: To live as one with the poor. This meant that their dress, their meals, their entire way of life was to be no different from the average subsistence farming family in the area. For those who opted to join the project, this represented a near complete break from worldly goods or material possessions. Before they set out for Alukalawita, Father Mike asked his companions “Are you willing to bear the cross?”

It was not a grandiose statement, as they soon found, but a reflection of the hardships endured by the majority of our population.

His work did not occur in a vacuum. In addition to being a liturgical scholar, Father Mike was highly attuned to the global context in which local struggles unfolded

Father Mike was no ordinary missionary. He had no intention of converting the rural Sinhala masses to Christianity. Though he already had two PhDs, he was a student at heart. Thus, he began his work in Buttala in a spirit of learning, listening closely to the local community who at the time were caught in the crosshairs of the green revolution, the rise of the plantation economy, and the slow poisoning of their land and waters by the agrochemical industry.

Suba Seth Gedara

Father Mike’s first step was to survey the poorest households in the area to identify their most basic needs and aspirations. Through lengthy discussions with the villagers he learned that issues of health and education were foremost on their minds. From these encounters, a publication called ‘Avabodaya’ was born. Meaning ‘awareness’, this simple village circular served as a kind of knowledge hub for the community where ordinary people could voice their concerns or share solutions to collective problems.

It became clear that the villagers urgently required access to inexpensive remedies for a range of sicknesses caused by the proliferation of pesticides and chemical fertilizers from the nearby sugarcane plantations. With the closest hospital being many miles away, one Avabodaya contributor floated the idea of a herbarium filled with medicinal plants. The residents at Suba Seth Gedara quickly convened a group to undertake a careful scientific study of indigenous plants and herbs. They travelled to neighboring estates and met superintendents to gain access to plantation libraries, which were crammed full of often unused reference material. Armed with knowledge of scores of native plants, the team then visited ‘Veda Mahaththayas’ and ‘Veda Nonas’—Ayurveda doctors—to learn about the medicinal properties of plants. All of their findings were published in Avabodaya. Eventually the community secured the funds to establish their herbarium.

It was a small victory, but one that reflected Father Mike’s vision for rural development; not charity or a deluge of ‘solutions’ dictated from a lofty perch, but a participatory process of communal awakening. Father Mike had the same unshakeable belief in the people as he had in the Almighty—he believed they possessed the consciousness, creativity and capacity to chart their own path towards a decent life. He was, as one of his companions said to me, the living liturgy.

His work did not occur in a vacuum. In addition to being a liturgical scholar, Father Mike was highly attuned to the global context in which local struggles unfolded. With his Marxian outlook he stitched together a portrait of rural Sri Lanka that reflected international geopolitics—the exploitation of the peasantry and labourers by multinational corporations, the environmental impacts of neoliberalism, and the urgency of returning to an indigenous way of life, in harmony with nature, using traditional knowledge systems and ancient cultural practices.

It was a prophetic vision that has tremendous significance for the current moment. While he may not have foreseen a viral pandemic, Father Mike certainly predicted a crisis of capitalism that would require a shift away from the import-export model of economics towards a strong, sustainable and local system of production and exchange. He knew such a change would not come easily—and that the hardest task would not be pressuring governments or picketing companies but summoning the internal conviction to adopt a new way of being.

Father Mike was assassinated on November 10, 1987. Minutes before his murder, as he performed mass for the residents of Suba Seth Gedara, he echoed the words of the slain Salvadorian priest Oscar Romero: “I have often been threatened with death. I have to say, as a Christian, that I don’t believe in death without resurrection: if they kill me, I will rise again in the […] people. I tell you this without any boasting, with the greatest humility. I am obliged, by divine command, to give my life for those I love.” He had barely finished speaking when the fatal shot rang out.

Of course, he did not rise again, and none were held accountable for the killing.

But perhaps it is fair to say that he and his brigade of barefoot revolutionaries experienced a resurrection of a different kind through their work in Buttala. By letting go of the past and plunging into the unknown, they chartered a course that is now more relevant than ever before. From wilderness and destitution, they fashioned a thriving, inter-religious community and sowed the seeds of wellness, justice and literacy that continues to bear fruit.

While the world scrambles to reconceive itself, we in Sri Lanka need look no further than the little house called Suba Seth Gedara where—once, briefly—a garden of Eden flourished.

28 Nov 2024 51 minute ago

28 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 3 hours ago