24 Mar 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The medical profession in Ceylon had by the late 19th century followed patterns set down in most of the European  colonies in Asia. The Civil Medical Department was set up in 1858, the Ceylon Medical College in 1870, the Ceylon Medical Association in 1887.

colonies in Asia. The Civil Medical Department was set up in 1858, the Ceylon Medical College in 1870, the Ceylon Medical Association in 1887.

As with law, the practice of medicine soon came to be monopolised by the upper-middle class, predominantly Burgher and Tamil. Kamalika Pieris, in her extensive study of the evolution of the profession in British Ceylon, conjectures that this may have been due to the fact that unlike the Sinhala bourgeoisie, neither the Burgher nor the Tamil middle class had extensive holdings in the land. Kamalika’s father, Ralph, contended that in colonial society, the quickest way for the middle class to maintain their status was by ensuring that their children took to professions where the duration between the completion of a degree and the finding of employment was brief; to give just one example, Lucian de Zilwa, divided between law and medicine, chose the latter because “I could begin to earn something the moment I received my sheepskin.”

The entrenchment of a medical elite did not contribute to a rise in health or sanitary standards in the country. The first hospitals had been built primarily for military garrisons in Colombo, Galle, Jaffna, and Trincomalee, while the  growth of the plantation economy necessitated the building of hospitals elsewhere to service the needs of estate labour. Clearly, in both cases, the aim was to serve imperial interests.

growth of the plantation economy necessitated the building of hospitals elsewhere to service the needs of estate labour. Clearly, in both cases, the aim was to serve imperial interests.

Against that backdrop, expansions of medical institutions, quarantine centres, and isolation camps were driven by bouts of epidemics which became part and parcel of the subcontinent in the 19th century. The objective of this essay is to compare and contrast the responses by officials to two such epidemics: smallpox and cholera.

Historically, the Sinhalese are said to have feared smallpox the most. Robert Knox wrote that none of the charms and enchantments “Successful to them in other distempers” could cure the illness. Ribeiro described it as “The most dreaded disease among the natives.”

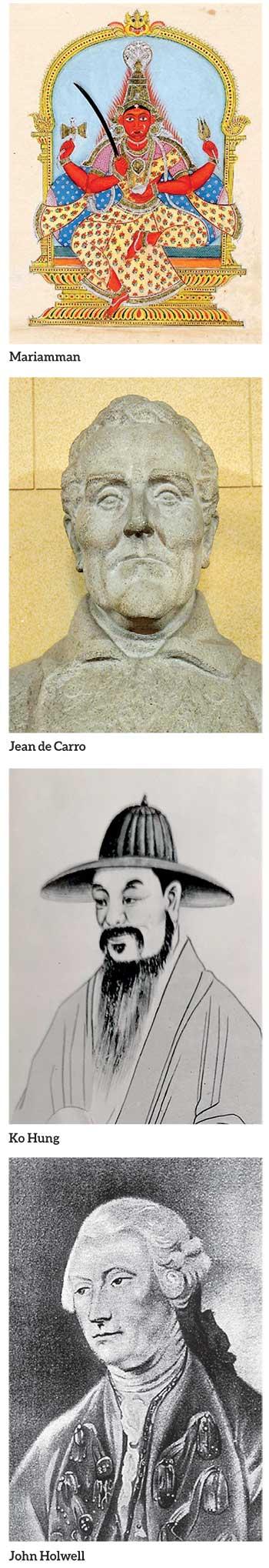

There’s reason to believe that while smallpox was introduced to the colonies by European adventurers, it did exist in pre-colonial society, even in here; Asiff Hussein writes of Hugh Neville describing “a gigantic Telambu tree amidst a sacred grove on the site of the Ruwanveli dagaba” which may have figured in an outbreak of a disease at the time of Arahat Mahinda. The first recognisable account of the disease, according to Thein (1988), comes to us from the fourth-century Chinese alchemist called Ko Hung; it may have existed in a mild form in fifth-century India.

John Holwell was the first British official to write on the illness in the subcontinent, in 1767 in Bengal. From 1779 to 1796, there was a severe smallpox outbreak in that region, while in 1802 we read of a Swiss doctor, Jean de Carro, sending samples of a vaccine to Bombay via Baghdad.

According to Meegama, it was in 1802 also that vaccination against smallpox was started in Sri Lanka. However, owing to inconsistencies in the vaccination program, not least of which being the slipshod way medical officials despatched vaccines to poorer, far-flung regions, there were severe periodic outbreaks.

In 1886, vaccination was made compulsory for the first time, but even then problems in the Medical Department, set up 28 years earlier, led to the disease spreading throughout the country. To prevent it would have meant enforcing a comprehensive anti-venereal program, which transpired 11 years later with the passing of the Quarantine and Prevention of Diseases Ordinance No. 2 of 1897. By the 1930s, smallpox had ceased to become a serious threat; by 1993, it had been fully eradicated.

"The apogee of this trend, no doubt, was the malaria epidemic of the 30s and 40s, in which the work of volunteers was done, not by the English speaking Westernised medical elite, but by a group of young Leftists..."

No less feared than smallpox was cholera, which like smallpox goes back many centuries in the country and the subcontinent. The Tamil goddess, Mariamman, is considered symbolic of both smallpox and cholera, while a reference in the Mahavamsa to a yakinni who in the reign of Sirisangabo caused those who came under her curse to have red eyes and die the moment they came into contact with a patient, may indicate an outbreak in as early as third century Sri Lanka.

Historical sources tell us of a reference in ninth-century Tibet to a particularly violent illness (the first signs of which included “violent purging and vomiting”), although scholars doubt the authenticity of these texts.

In any case, not for nothing did colonial officials call it the Asiatic cholera, given its ancient origins in the lower Bengal where it must be said, we come across our earliest sources for the cult of a cholera goddess in the subcontinent. On the other hand, the destruction of the local economy, and unnatural changes in agriculture forced on farmers by British authorities, had an impact on these outbreaks: with irrigation schemes destroyed and neglected, water scarcities could only result in pestilence.

There were six cholera pandemics between 1817 and 1917, all of them aggravated by certain disruptive economic and social changes unfolding in each period they occurred in.

They all originated from the Bengal, in keeping with the genesis of the disease in tropical, depressed climates, and they all diffused gradually beyond the region, to as far as Russia, the US, and Latin America. Each pandemic was progressively deadlier than the previous one, and they all left behind heavy death tolls in the places of origin. The first case in Sri Lanka was reported in 1818 in Jaffna.

However, as Meegama (1979) notes, the disease never became endemic in the island, and it turned into a serious issue only after the British, having destroyed and then forcibly appropriated Kandyan lands under the Crown Lands Encroachment Ordinance and Waste Lands Ordinance of 1840, opened plantations and imported coolies from South India. The latter led to contagion: the number of cases hiked from 16,869 between 1841 and 1850 to 35,811 in the following decade, with fatality rates rising from 61% to 68%.

Until the passing of the Quarantine Ordinance in 1897 – by which time five of the six cholera epidemics had passed through the country – officials took haphazard measures to control the immigration of South Indian labour.

Most immigrant workers, on their way to the plantations, took the Great North Road to the hill country, which brought them into contact with locals in Jaffna and Mannar; this led to frequent severe epidemics between 1840 and 1880, after which we see a reduction in the number of cases and fatalities.

Still, officials remained oblivious to the need to quarantine estate workers until much later, a problem compounded by the fact that many coolies, long after restrictions had been imposed on them, came disguised as traders: a conundrum attributable as much to the immigrants as it was to “the partial manner” in which the quarantine was enforced by officials. Two years after the Ordinance was passed, the Great North Road was closed to coolies, who were then taken upon entry to the country to Ragama. However, other problems cropped up: as Kamalika Pieris points out, there was widespread hostility to Western medicine among locals, particularly in backward regions, while doctors never actively tried to reach those areas. Contaminated water became a serious issue even in Colombo, as did unplanned urbanisation, and quarantines led those fearing for their lives to flee to other districts, spreading the disease even more.

De Silva and Gomez (1994) note that one of the contributing factors to the recession of these diseases were the strides made among the general population in sanitation. The first soap was imported to the island in 1850; until then, vegetable oils had been widely used. The setting up of various Committees to probe the reasons for outbreaks of diseases, no doubt analogous to the many Committees administrations here today set up to probe reasons for national crises, would have been another contributory factor, but the main point to be gleaned from the two case studies examined here is that the colonial government, while having resources to expand into less well off regions, chose for crude reasons of an economy not to.

By the 1930s, at which point cholera had been significantly contained – in 1946, two years before independence, only two cases were discovered – the rise in a radical left movement among professionals in the island, including doctors and lawyers, led to a proactive approach being taken in the face of pandemics and contagions.

The apogee of this trend, no doubt, was the malaria epidemic of the 30s and 40s, in which the work of volunteers was done, not by the English speaking Westernised medical elite, but by a group of young Leftists, among them perhaps the first Western doctor to don the national dress, S. A. Wickramasinghe.

The writings of S. A. Meegama, Asiff Hussein, Kamalika and Ralph Pieris, Robert Pollitzer, Ariyaratne de Silva, Michael G. Gomez, and M. M. Thein were used for this article.

28 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 3 hours ago