07 Feb 2019 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

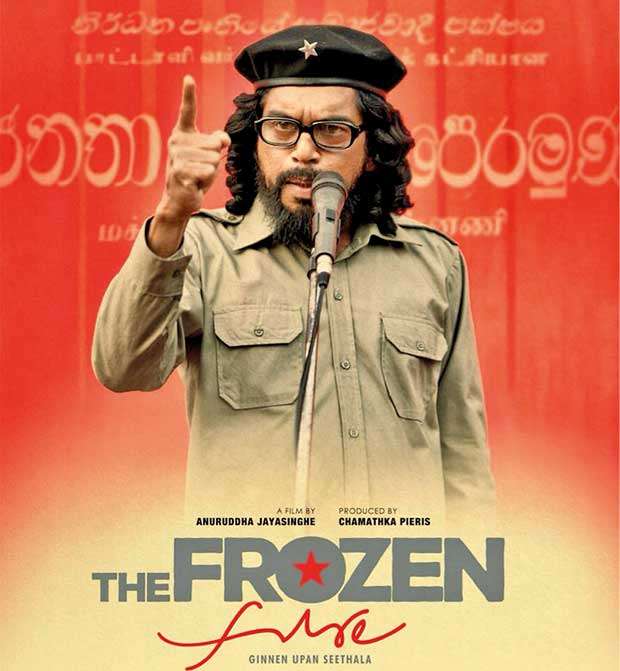

‘Ginnen Upan Seethala’ (The Frozen Fire) is a movie that was asking to be made. It’s about the life of JVP leader Rohana Wijeweera and his bid to change the political history of Sri Lanka through armed insurrection.

‘Ginnen Upan Seethala’ (The Frozen Fire) is a movie that was asking to be made. It’s about the life of JVP leader Rohana Wijeweera and his bid to change the political history of Sri Lanka through armed insurrection.

The resulting picture is so confusing that even the final death count varies widely. It was considerable and the damage to the country’s psyche even more drastic. The simple fact that no two Sri Lankans having a conversation in the street will trust a third party within earshot is the direct result of these two failed rebellions and the counter-terror which crushed them.

That even controlled protest such as trade union action isn’t allowed in many sectors is another blow to the practice of negotiating democratically. That a very powerful military has a say in our semi-democratic form of government is another disturbing result of Wijeweera’s political goals and means. This has its insidious effects of social life as well as the arts. For example, the rule that the depiction of members of the security forces in film needs approval from the censors can hardly be called a democratic practice.

Rohana Wijeweera is the most fascinating political leader and participant in the country’s post-independence politics. More than a participant, he was a mover and a shaker. Much has been written about him, most of it inconclusive and partisan, and a movie was waiting to be made.

Now that it’s finally there, what does it tell us? Director Anuruddha Jayasinghe was a student of Thurstan College, Colombo, when he was arrested as a JVP activist during the late 1980s second JVP rebellion. That he sees the movie from a partisan point of view is understandable. That he’s an admirer of the late JVP leader is quite acceptable. The trouble is that he seems to have made this historic movie with his heart, not his mind.

Kamal Addaraarchchi, easily the most promising talent in film in the 1980s, lost his way. But he has made an impressive comeback in the role of Wijeweera, something which undoubtedly called for great commitment and determination. But his performance is marred by flaws in the character as scripted, and let’s try to see what these flaws are.

What we get here is a soft-spoken and benign Wijeweera. He is a moderate, cautionary figure keeping the hotheads in his inner circle at bay. He is a loving family man. In this version, it’s his attachment to his family which causes his downfall, when he ignores calls by fellow politburo members to flee his last refuge.

All that’s fine, but is that all there is to a man responsible for two very bloody Sinhalese youth rebellions in modern history? According to some sources, the combined death toll exceeds that of the 30-year civil war with the LTTE. How did he hold the volatile personalities of his politburo (PB) together? How did he deal with dissent?

These are questions left unanswered by ‘Ginnen Upan Seethala.’ According to it, the DJV or military wing of the JVP is an independent entity led by its leader Keerthi Wijebahu with a free hand. It’s the DJV’s rash decisions which led to the failure of the second JVP uprising. Was Wijeweera powerless to intervene or did he lack the political foresight and the will to veto the DJV’s disastrous orders to the rank and file? This is hardly credible.

All that’s fine, but is that all there is to a man responsible for two very bloody Sinhalese youth rebellions in modern history? According to some sources, the combined death toll exceeds that of the 30-year civil war with the LTTE. How did he hold the volatile personalities of his politburo (PB) together? How did he deal with dissent?

The ideological rift with Nandana Marasinghe, one of the more politically astute and dynamic PB leaders, is shown but we see only half the story. Marasinghe’s killing was ordered by his fellow PB members including Wijeweera. In the movie, though, the decision what to do with him is postponed by the PB and Nandana Marasinghe isn’t heard of any more. Anyone not familiar with this history would assume that Marasinghe disappeared on his own free will.

This movie leaves more questions unanswered. We see an endless series of PB meetings which dampens the impact of a story which should leave us at the edge of our seats. Less time talking and more time spent with the actual action would have given us the ‘biographical thriller’ which the brochures promise. As it is, both the biography and the thriller have gaping holes.

To the director’s credit, some of the action scenes (such as the ethnic riots, political meetings, and a dramatic scene where military vehicles drive at night through pouring rain) are very well staged. But that’s just not enough, and many scenes could have been better edited, for example the scene where a JVP youth orchestra plays early in the story. It’s much too long.

It’d be interesting to compare this movie with Stephen Soderberg’s‘Che’ (2008, in two parts). It was criticised for showing mostly Che the public figure, and little of his private life. With ‘Ginnen Upan Seethala,’ the criticism is that it shows too much of the private life. Both portraits are sympathetic, but in the latter case we want to know more about Wijweera than just how much he loved his wife and children.

Soderberg’s Che is played by Mexican actor Benicio del Toro. He’s not an exact look alike, but more importantly he gets under the skin of his character. In our case, Addararachchi doesn’t have much to go by as he follows the script which gives us a moderate figure whose bid to enter mainstream democratic politics is thwarted by the autocratic President JR Jayewardene, the villain of the piece.

In the final analysis, no agreement will ever be reached on that point – if JR didn’t proscribe the JVP, would Wijeweera and his cadres have given up the armed struggle? This is a tricky point. He rejected a peace offer from JR’s successor R. Premadasa when the insurrection was at its height. Experience had undoubtedly taught him to distrust the politicians. What did his own nature dictate?

The movie ends with the arrest of Wijeweera, thus leaving out the harrowing details of his execution. By some accounts, he was shot at the Colombo general cemetery but was still breathing when his body was thrown into the incinerator. This isn’t an episode that the country can be proud of?

By comparison, Abimail Guzman, the Peruvian leader of Sendoro Luminoso guerrilla movement which led a brutal 20-year-old war against the government of Peru, was spared after his arrest. So were his top aides. Guzman is still in prison but was allowed to marry and helped negotiate a peace settlement with his cadres. This is how our story too, should have ended. Instead, we keep taking grim satisfaction in a smug ‘ serve them right’ attitude while the smouldering socio-political problems which created Rohana Wijeweera continue to smoulder.

Nadeeka Guruge has done an effective score while Dhanushka Gunathilake’s cinematography is excellent, especially the outdoor night scenes. The script, editing and some of the acting leaves much to be desired. For example, in a crucial scene where Wijeweera and his PB members react in dismay to the arrest of a colleague, they behave not like hardened revolutionaries but a bunch of schoolboys reacting when their favourite batsman gets out for a duck.

Despite such flaws, this is a historically important film and marks a milestone for the Lankan film industry. Along with ‘Nidahase Piya DS’ screened last year (about D. S. Senanayake), the political biography is now in demand as subject matter for Sri Lankan films. It’s a heartening development.

30 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 5 hours ago

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024