30 Nov 2019 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

2019 proved Sri Lanka is not India and certainly not the US

In Sri Lanka, politics is hardly ever built on consensus

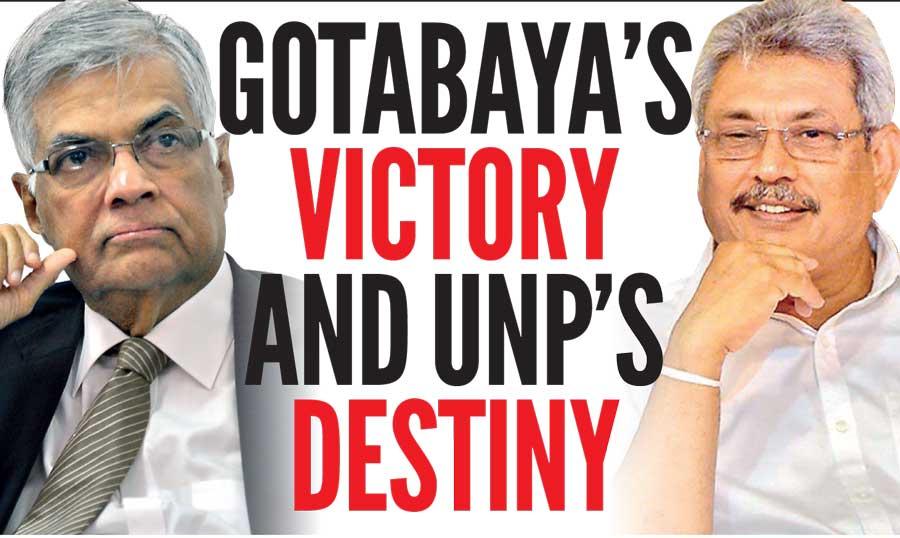

Gotabaya Rajapaksa won. That does not mean Ranil Wickremesinghe lost. The Sajith faction in the UNP naturally wants him out. At the same time, they are afraid of suggesting names. So we have Hirunika Premachandra who acknowledges him as a walking, talking library, telling journalists at a press briefing that while the dear leader wants the leadership changed, many of those around him are prevailing on him not to go ahead with it. Elsewhere, when quizzed about whether the Sajith troupe would resort to legal means to topple the Ranil troupe, the ever-affable Eran Wickramaratne replies, “No one has looked into that possibility so far.” They are impatient, yet also cautious. This, if you think about it, is a testament to the draconian nature of the UNP Constitution (as amended by Ranil). They want reform, they want a change of the guard, but they can’t get it. The Ranil faction, with or without Ranil, is too strong. The stakes are too high. Meanwhile, the winner from all this continues to be the man in power.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa won. That does not mean Ranil Wickremesinghe lost. The Sajith faction in the UNP naturally wants him out. At the same time, they are afraid of suggesting names. So we have Hirunika Premachandra who acknowledges him as a walking, talking library, telling journalists at a press briefing that while the dear leader wants the leadership changed, many of those around him are prevailing on him not to go ahead with it. Elsewhere, when quizzed about whether the Sajith troupe would resort to legal means to topple the Ranil troupe, the ever-affable Eran Wickramaratne replies, “No one has looked into that possibility so far.” They are impatient, yet also cautious. This, if you think about it, is a testament to the draconian nature of the UNP Constitution (as amended by Ranil). They want reform, they want a change of the guard, but they can’t get it. The Ranil faction, with or without Ranil, is too strong. The stakes are too high. Meanwhile, the winner from all this continues to be the man in power.

The Sajith faction’s loss can be squarely attributed to the dillydallying and dithering of their leader. Ranil played a role there not too different to that played by Maithripala Sirisena in the lead up to the 2015 general elections: feigning assent to his party’s choice of candidate and then, at the very last minute, declaring his intention to remain at the top after the election. In all probability, even if his candidacy were confirmed on time, Sajith would not have won, but the margin would have been less wide. On the other hand, even with his candidacy confirmed he still had several obstacles to wade through. These were apparent from the word go, though those clamouring for a UNP under Sajith didn’t notice them; they contributed to a severe defeat despite, not because of, the man leading the campaign. To name them all would be tortuous. But in a context where the opposition has gone back to 2010 (weak, weakened and weakening), the UNP must reflect on why it must reform, quickly.

People may laugh at Ranil Wickremesinghe’s statement that he got the North and East to vote for his party candidate. At one level, however, it’s true. Tamil politicians may not have gone gung-ho over their endorsement of Sajith Premadasa, and yet even if they did, it was because of Ranil: we have it from at least one prominent minority party leader that they did not place much confidence in Sajith. What transpired in the meeting between the UNP and these parties and what was discussed will not, I believe, be revealed any time soon. But Ranil’s remark has a ring of truth to it: he ensured the North and East, and by implication left the South to the man installed as the candidate. To be sure, none of those who argue that Rajapaksa racialised the election (“1956 reborn!” writes Victor Ivan) will comment on what Ranil said. It shows how racialised his strategy was: one faction “getting” the north and east (Tamil and Muslim), and the other “getting” the South (Sinhala); as one commentator noted, “Ranil Wickremesinghe has found religion, and the name of that religion is Sinhala Buddhism.”

In Sri Lanka, politics is hardly ever built on consensus. The result, obviously, is polarisation, whereby seats, regions, and districts traditionally blue and green invariably go blue and green and whereby parties put up a big fight to make and keep them blue and green. The SLPP, as I have written before, had pragmatically “abandoned” six districts which it knew it would lose. The UNP, on the other hand, had to get massive margins across those six districts. If the idea was to present Sajith Premadasa as a politician rooted in consensus, the party had to canvass votes beyond those districts also. In that regard, putting in Sajith was a first step, but not the only step. This is because while he was the definitive if not disputed candidate of the UNP, he was not the UNP. The party had chosen him, yet the party could very well do without him; while there was no other option, he was not the most viable option. The man had to keep the momentum going, beyond his father’s legacy, and make his Premadasist ideals palatable to the multitude of underprivileged, depressed southern peasants for whom the UNP under its leadership represented a deviation from those same ideals. He could not.

Eventually, the party got entangled in one contradiction after another. Making his stance on decentralisation clear, Sajith implied that Rajapaksa promised one form of devolution to India and another form after he returned to the country. Ironically the same could have been said of Sajith’s own party’s stances. Chandraguptha Thenuwara’s remark on ranawiru gaaya, Victor Ivan’s remarks on drafting a new Constitution (which he made on the UNP’s platform when he could, and should, have talked about Sajith’s economic programme), and the coming together of several forces seen (fairly or unfairly) as hostile to the majority community did not help him one bit. Indeed, it took a stalwart from Ranil’s camp to say it for what it was: Lakshman Kiriella, pondering on their loss at Temple Trees after the election, suggested that no minister hurt Buddhist sentiments more than Mangala Samaraweera.

The North-East/South racial divide should be called out and condemned. On the other hand, that divide had a class dimension to it: the poorer districts went to Rajapaksa, the prosperous ones went to Sajith. The bourgeois vote went to Sajith, but chunks of it, along with the petty bourgeois and rural vote, went to Gotabaya. Race wasn’t the only factor; if Sinhala Buddhists were voting for Gotabaya because they were anti-Tamil and anti-Muslim (which is essentially what commentators now suggest), this does not explain why Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa, the twin peaks of Sinhala Buddhist civilisation (far more so than the South) were secured by the SLPP by surprisingly thinner than expected margins: 24% and 13% leads respectively. It also does not explain why Bandaragama, a seat with a significant Muslim population, secured a thumping 30% lead for the “nationalist” candidate. As with Brexit and Donald Trump, most mainstream columnists could not predict the impact economic factors would have on the results. The consensus was that neither of the candidates could obtain more than 45% while Anura Kumara Dissanayake, who had wooed disaffected, disenchanted petty bourgeois artistes and academics from Colombo, could get around, if not more than, 5%.

As for the youth vote, even this writer believed, not without reason, that it would be snatched by Mahesh Senanayake, particularly since his conduct after the Easter attacks had entranced those shocked by the UNP’s negligence, the SLPP’s chest-thumping rhetoric, and the JVP’s perceived subservience to the UNP.

In that sense, 2019 proved that Sri Lanka is not India and certainly not the US. While voting patterns are determined by racial and religious considerations across geographic frontiers as they are in much of the West, those considerations, regardless of what columnists will write about how they tend to dominate the political discourse, do not prevail over others; if they did, Sivajilingam would have won in the North, Hizbullah would have won in the East and Ariyawansa Dissanayake would not have outrun Sivajilingam on his own turf. In that sense, the opinion of one columnist that the populist frenzy won the presidential election, even when we know that the other guy played to populist sentiments as well, shows how writers misread political contexts far removed from their political space.

I believe that class and geographic affiliations, as well as the sense of belonging to a deprived class, determined the election outcome. I may be wrong, yet I am certain that race was merely one factor. I also believe that people were voting for parties as well as for personalities. The TNA endorsed Sajith not because he was the best option, but because he was the only option, just as they endorsed Maithripala because he was campaigning against Mahinda. The same could have been said of the Sinhala Buddhist peasantry who went in large numbers and voted for Gotabaya: they were mindful that he was not a populist promise maker like Mahinda, but since his party was the one opposing the UNP, they put him in. Each voted against the other over policies and over articulation of policies. The populist, with all that, could have got the numbers. He almost did. The reason he could not was the party he was contending from; one that housed stalwarts seen to be anti-Sinhala and anti-Buddhist. In the end, then, Sajith lost because of the party. If he is to win through the party, it must be reformed.

28 Nov 2024 6 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 7 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 8 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 9 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 28 Nov 2024