04 Dec 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

- Many experts in the country had serious doubts about the robustness of that initial success

- Whatever level your testing is at, doubling testing intensity (TCR) reduces the spread of COVID-19 by the same amount on average

- The health ministry did not substantially increase testing, and those in charge repeatedly declined offers to obtain large PCR machines

By Ravi P. Rannan-Eliya, Nilmini Wijemunige, Nishani Gunawardana, Sarasi Amarasinghe, Ishwari Sivagnanam, Sachini Fonseka, Yasodhara Kapuge, and Chathurani Sigera (Institute for Health Policy)

Yesterday (December 3, 2020), we published in a leading US health policy journal a major research study

|

Dr. Ravi P. Rannan-Eliya who led the IHP team is Executive Director of the Institute for Health Policy (IHP). He trained as a physician at Cambridge, and in public health and economics at Harvard. |

that we did to assess the impact of PCR testing on the spread of COVID-19 [1]. This was done in Sri Lanka by Sri Lankan researchers using Sri Lankan funding. We want to share what we did, what we found, and why we think it is important.

Why we did this

As we successfully defeated the first wave of COVID-19 in April, many experts in the country had serious doubts about the robustness of that initial success. They include leaders of the medical profession such as Prof. Vajira Dissanayake, Prof. Harendra de Silva and Dr Ruvaiz Haniffa, but there were others, and we cannot forget the GMOA. As health professionals without a partisan political agenda, we repeatedly expressed our concerns that the country was not doing enough PCR testing to adequately control the virus and to prevent future outbreaks. Our public words and private communications to those in authority fell on deaf ears. The health ministry did not substantially increase testing, and those in charge repeatedly declined offers to obtain large PCR machines.

Their failure did not arise out of malign intent. Most public health experts here and internationally did not appreciate the critical importance of PCR testing. That thinking led advanced countries like the UK and USA to make serious errors, leaving tens of thousands of their citizens dead, whilst developing countries like China and Vietnam crushed COVID-19. While the WHO did urge more testing, its recommendations were not sufficient to persuade our health ministry to change its policy.

"Our results indicate that there is no optimal level of testing as the WHO and others have suggested"

We needed solid scientific evidence to press our case, especially if it meant breaking with global consensus. But we were surprised to find that none existed. Even the WHO admitted that it lacked a scientific basis for its recommendations. So we started our own research to assess the impact of PCR testing on the spread of COVID-19. Our initial goal was to change policy in Sri Lanka, but when we obtained our first results, we realised that we had hit on something important that much of the world was ignoring, and we decided that we had to do this properly and publish it internationally. Another consideration was that without doing that many people here would doubt our work. Doing this took a very long time—it is not so easy to publish research challenging conventional thinking if you are writing from Sri Lanka and if you decide not to include authors from rich countries to improve your credibility. Perhaps too long—my deepest professional regret this year is that our research comes out too late to prevent our second wave, but I am not sure what else we could have done.

What we did

To look at what effect PCR testing has on COVID-19 spread, we used a form of statistical analysis, known as linear regression, to look at the impact of different factors on the differences in transmission across different countries. This has been used by hundreds of COVID-19 studies previously, many of them published in leading international journals, so this would not have produced anything new. But we did three things in combination that other international researchers had not done.

"We are not going to be able to eliminate COVID-19 anytime soon with a vaccine"

First, we included a measure of the intensity of testing effort in our analysis—the ratio of tests to each new case, what we call the Test-to-Case Ratio (TCR). Most researchers had not attempted this before, because the data hadn’t been collected for most countries, but we spent weeks searching the web to find that data for almost all countries in the world.

Second, unlike previous studies that focused on one issue or the other, for example the effect of temperature or the effect of lockdowns, we looked at everything at once. This is important because when you only look at one thing at a time, you can never be sure if something else that was left out explains what you see.

Third, we addressed a problem that other researchers have faced, but had not solved. This is that the data for most things that we want to examine do not exist for all countries. For example, China might not publish national data on how much it tests, and Google might not publish mobility data for India. If you want to include both in your analysis, what this usually means is that you have to exclude both countries. It turns out there is a way of getting around this, known as multiple imputation, which is used by some medical researchers, but rarely in public health, so we used that.

Once we did this, we could estimate the impact of a range of interventions and other factors, such as climate and income on the average speed of transmission of COVID-19 in almost all countries during the first wave. And we could do this much better than any previous study, since our final analysis explains more than 80% of the variation in country performance during March to June. That is what we just published.

What we found

Our study generated many findings. So many that we could not mention all of them within the word limits that scientific journals impose, and certainly too many to discuss here. But the key finding is that the intensity of PCR testing had the greatest effect on COVID-19 spread of all the interventions we looked at. Far more than school closures or masks, while lockdowns turned out to usually make things worse than better, especially in developing countries like ours. We also found that cooler temperatures and air pollution help the virus to spread, but these are not big effects. Being rich or poor, or having a good or a bad health system, or having BCG vaccination also made no difference to how countries performed.

"All it takes is effective contact tracing and isolation to then stop the virus spreading"

Whatever level your testing is at, doubling testing intensity (TCR) reduces the spread of COVID-19 by the same amount on average. If a country increases testing enough, it can reduce COVID-19 transmission, enough to eliminate the virus altogether, in much the same way that really good vaccines do.

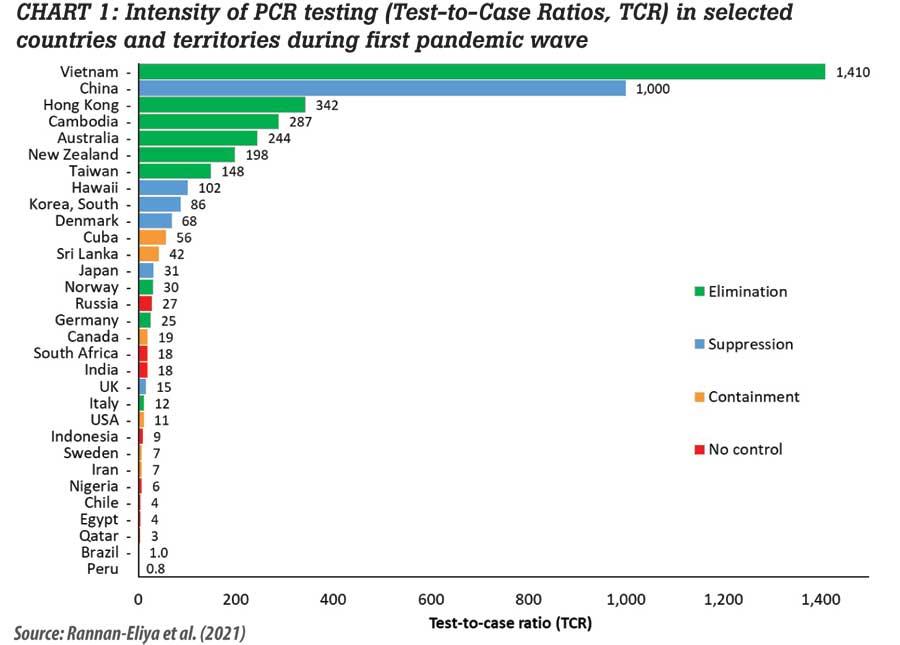

The other important finding was how much countries vary in their testing effort. President Trump claimed that the USA leads the world in testing. But using our TCR measure, the USA has very low levels of testing, doing only 11 tests for every case. Sri Lanka did better (TCR=42), but the really successful countries like Australia and Vietnam were doing several hundreds of tests for each new case, as shown in the chart.

Why does increasing testing always reduce COVID-19 transmission more?

Our results indicate that there is no optimal level of testing as the WHO and others have suggested. Increasing testing always seems to slow COVID-19 spread even more. The explanation lies in what the high testing countries do. The more a country tests, the more it tests people in the community with minor symptoms, for example coughs and colds. That is what Australia now does. These people may be very unlikely to have the virus, but the more of them that you can test, the more infected people that you can identify. The more of them you find, the faster you can eliminate the virus in the community. All it takes is effective contact tracing and isolation to then stop the virus spreading.

What this means

Our results have many implications not only for Sri Lanka but also for the global control of COVID-19. The most important is that increasing testing is always better. Many Asian countries and Australia and New Zealand did well because they tested more, while the USA, most of Europe, India and much of the world did badly because they did not increase testing enough and as fast as needed.

"Our public words and private communications to those in authority fell on deaf ears"

The only real question is how much you need to increase testing. This depends on what else you are doing. If the other measures you are doing are working, then you don’t need to test so much. On the other hand, if you don’t want to take those other measures or you don’t want to inconvenience the public with say school closures and lockdowns or forcing them to wear masks, you can do so if you increase routine testing enough. This might seem impossible, but we can see this happening right now in places like Australia and New Zealand which are basically free of COVID-19.

Overall, our analysis largely explains why some countries did well and why some did badly, and more importantly our results provide strong scientific evidence that Sri Lanka wasn’t testing enough during May to August.

We are not going to be able to eliminate COVID-19 anytime soon with a vaccine. But we do not need a vaccine to eliminate the virus or prevent outbreaks. This can be done through a strong programme of testing, tracing and isolation. Our public health staff and military have shown that they can do the last two better than almost all the world. The missing part is PCR testing—we need intensive PCR testing to prevent outbreaks, and of course to control the current outbreak.

"Our results provide strong scientific evidence that Sri Lanka wasn’t testing enough during May to August"

"The more a country tests, the more it tests people in the community with minor symptoms, for example coughs and colds"

Our study provides strong scientific evidence that our national COVID-19 strategy needs to change, and that we need to increase routine PCR testing, focusing on people in the community and presenting in primary care with coughs and colds. PCR testing is expensive, but the high levels of testing that are needed to successfully control and prevent COVID-19 outbreaks cost far less than the economic damage, lost jobs and loss of human life that we are already suffering.

As Sri Lankan researchers, we have done our part. We hope that the government listens and makes the necessary changes, because only our elected politicians can do that.

Rannan-Eliya RP, Wijemunige N, Gunawardena JRNA, Amarasinghe SN, Sivagnanam I, Fonseka S, Kapuge Y, Sigera CP. Increased Intensity Of PCR Testing Reduced COVID-19 Transmission Within Countries During The First Pandemic Wave. Health Affairs; (Ahead of Print): https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01409

27 Nov 2024 32 minute ago

27 Nov 2024 41 minute ago

27 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

27 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

27 Nov 2024 2 hours ago