22 Feb 2019 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A clarification, and an apology

Replying to my column last week (“Reflections on Sri Lanka’s Nationalisms”) Dr Dayan Jayatilleka posted the following comment:

“Ceylonism did exist and not only as the consciousness of a socioeconomic elite. The spearhead of the anti-imperialist movement, the LSSP and CPSL, was hardly pro-elite and was in the vanguard of the opposition to the comprador class. The identity of the Left, which was multi-ethnic, was not only Marxian class-based ‘proletarian’ internationalist, but a progressive Ceylonese one. This anti-imperialist Ceylonism was also the ideology of an upper middle class... quite distinct from the socioeconomic elite. This was the agency of Ceylon’s/Sri Lanka’s nonaligned ‘third worldism’. What after all, was the ideology of those who played the greatest role from among the Sri Lankans in the battle for a more just international order? A comprador Ceylonism or an ethno-nationalism? Obviously not! What was the ideology of Hamilton Shirley Amarasinghe, Neville Kanakaratne, Godfrey Gunatilleke, et al?”

I admit that conflating Ceylonism with the bourgeoisie was a mistake. While I was arguing about (and against) it in terms of the dichotomy drawn up between Ceylonese and Sinhala Buddhist nationalism, I was not aware of, or chose to ignore, the position of those who articulated neither: the radical sections of the middle and working class, to which the Left movement and the group that called itself the “Cosmopolitan Crew” (led by James Rutnam) belonged. This piece is an attempt at “clarifying” what was a more complex historical phenomenon: the bifurcation(s) of nationalism.

"In the colonial era there were three socioeconomic groups outside the peasantry: the conservative elite, the liberal middle class, and the radical class"

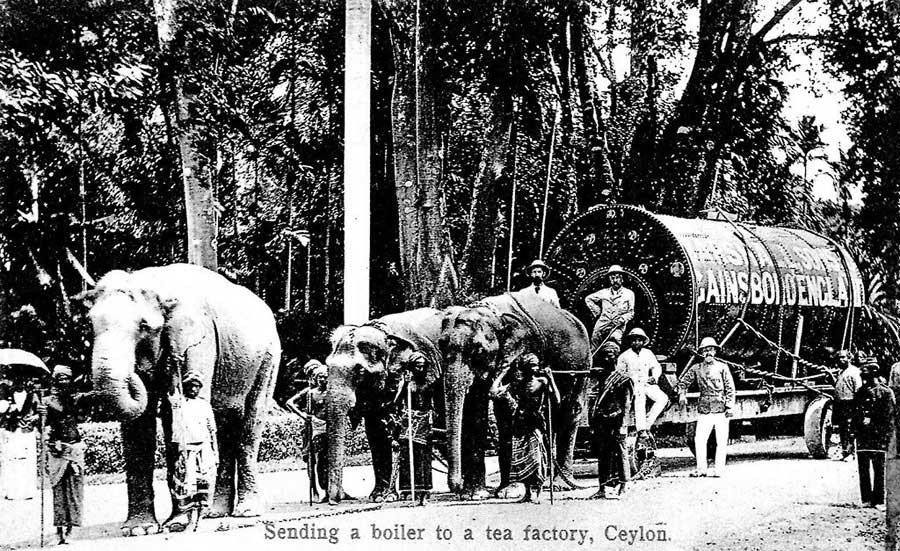

In the colonial era there were three socioeconomic groups outside the peasantry: the conservative elite, the liberal middle class, and the radical class. The second group did side with the third, but only insofar as its interests were not threatened; in other cases it sided with the first. It was amorphous: neither as uprooted as the conservatives nor as sympathetic towards class/communal aspirations as the radicals. K. M. de Silva’s assertion that this milieu was not uprooted from the world around it is hence correct, since the bourgeoisie could not remove themselves from the estate culture, which required frequent contact with workers, intermediaries, and officials.

Nationalism as understood by the conservatives meant loyalty to the British. The conservatives were opposed to any reforms which would clash with their privileges and hence “used their official positions and access to the British rulers to their own advantages.” On the other hand, nationalism as understood by the new bourgeoisie was more complicated. In fact the very nature of their enterprises, which put them at the mercy of colonial policies and global economic fluctuations (although they provided good returns), precluded any radical tendency among this milieu.

James Peiris articulated the complex relationship between the local capitalists and plantation officials when he stated that “the interests of the Ceylonese planters are identical with those of the European planters.”

A similar analogy can be obtained from France after the Revolution. While the Third Estate denounced the feudal nobility, they wanted power to pass to them, and not the peasantry.

Here the analogy becomes clearer. In France the middle class was opposed to the nobility. Like them, Sri Lanka’s equivalent of the Third Estate, the nobodies who became somebodies, at first clashed with the conservatives, and later sided with them. They were as willing as the Third Estate to go beyond the conservatives with regard to, say, the franchise, but only that far.

"By the time of the 1971 JVP insurrection, Ceylonism in the benevolent, rational, and socially equitable sense was eroding"

The snitch, though, was that it wasn’t ‘the people’ who were loyal, but those to whom the power to vote had been granted; by the time of the Donoughmore Constitution in 1931 only four percent of the population held that power. In fact universal franchise was never a demand of the Ceylon National Congress, which was more representative of the aspirations of the propertied and professional classes than the people even at its inception; the vote had to be granted in the face of opposition by the Congress. I like how Vinod Moonesinghe put it: “The right to vote had to be shoved down.”

The nationalism of the socioeconomic elite was in that sense a nationalism devoid of an ethnic or class content. It was “Ceylonese” not because it stood for a multicultural identity, but because it affirmed an elitist identity that transcended, or trivialised, the cultural contours of the nation.

But there was another Ceylonism, the Ceylonism of the Left in the early decades of the 20th century and of the SLFP following the 1956 election. Dr Jayatilleka writes on it extensively in his work Long War, Cold Peace, particularly in Chapter Four (“The International Dimension”). It was that which invigorated the most enduring legacy of the Bandaranaike years in terms of foreign policy: nonalignment.

"Here the analogy becomes clearer. In France the middle class was opposed to the nobility. Like them, Sri Lanka’s equivalent of the Third Estate, the nobodies who became somebodies, at first clashed with the conservatives, and later sided with them"

Dr Jayatilleka identifies three threats to Sri Lanka’s contribution to nonalignment: the UNP, presumably under the populist J. R. Jayewardene (whose contradictory political personality, oscillating between “Sinhala Only” and robber baron capitalism, is yet to be done justice to in a biography); the SLFP’s right wing; and the “ultra-nationalistic” domestic policies of the two Sirimavo Bandaranaike regimes.

In the transition in leadership in the UNP from the gentle Senanayake to the more scheming Jayewardene, there was a transition from the former’s liberal streak to the latter’s expedient populism. The same person who had mooted “Sinhala Only” and later opposed it would invoke the kings of the past to justify and sanctify the selling of national assets.

By the time of the 1971 JVP insurrection, Ceylonism in the benevolent, rational, and socially equitable sense was hence eroding. The country saw the last few embers of this Ceylonism more on the foreign policy front: Hamilton Shirley Amarasinghe, Dr Gamini Corea, Neville Kanakaratne, and Lakshman Kadirgamar, all of whom contrast discernibly with the level to which the Foreign Ministry stooped in both the Rajapaksa and the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe regimes.

On the domestic front, Ceylonism in the inclusive sense was disappearing faster. Ironically it was not the Sinhala Buddhist fascist monks and laymen who facilitated this, but the propertied professional class that had earlier stifled the rise of communal and class consciousnesses, to protect and preserve their interests. History, it would seem, is accursed with such ironies. Especially our history.

30 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024