23 Oct 2018 - 2473

Somewhere in my teenage years, I fell in love with the Sinhala song. Not songs per se, but the idea of the Sinhala geethaya. It was, I thought, unique and utterly different to the tunes I used to listen to over the radio, English, Hindi, or Tamil. And yet, like the meaning of love, it was difficult to put a finger on why, and how, it was so unique and different. Was it because of the composer? Couldn’t be. The vocalist? Surely not. The lyricist? Perhaps, but even there, I had my doubts.

Somewhere in my teenage years, I fell in love with the Sinhala song. Not songs per se, but the idea of the Sinhala geethaya. It was, I thought, unique and utterly different to the tunes I used to listen to over the radio, English, Hindi, or Tamil. And yet, like the meaning of love, it was difficult to put a finger on why, and how, it was so unique and different. Was it because of the composer? Couldn’t be. The vocalist? Surely not. The lyricist? Perhaps, but even there, I had my doubts.

What made it more difficult for me to ascertain this was the fact that modern local songs had next to nothing that could distinguish them from the tunes that invaded our airwaves. Over the years, the Sinhala geethaya had become democratised; we have gone from ‘obe neth dutu’ to ‘oyage lassana as deka dakka’.

It was then that I understood that, more than anyone else, it was the lyricist who made the Sinhala geethaya so unique. The uniqueness of the Sinhala lyricist had to do with the distinction, drawn in South Asia, between poetry and song, a distinction between an aesthetic based on the sounds in a language (“shabda dhvaniya”, for a song) and an aesthetic based on the meanings in a language (“artha dhvaniya”, for a poem). In both cases, it was language that preceded everything else.

It was then that I understood that, more than anyone else, it was the lyricist who made the Sinhala geethaya so unique. The uniqueness of the Sinhala lyricist had to do with the distinction, drawn in South Asia, between poetry and song, a distinction between an aesthetic based on the sounds in a language (“shabda dhvaniya”, for a song) and an aesthetic based on the meanings in a language (“artha dhvaniya”, for a poem). In both cases, it was language that preceded everything else.

It was not just aesthetic. It was also a rule, which served to discipline the poet and the songwriter in their fields. The latter, moreover, bore a bigger burden; he not only had to convey a feeling or sentiment through words, he also had to ensure that those feelings intermingled with the music. Not an easy task, you must admit.

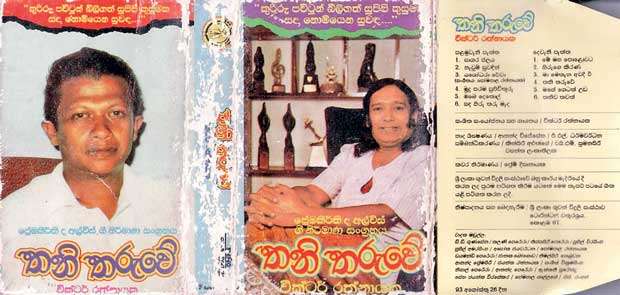

So I retuned to those lyricists. The songs they had written. The lines that had enthralled me. Some names kept coming back. Mahagama Sekara. Karunaratne Abeysekara. Ajantha Ranasinghe. Premakeerthi de Alwis. Of them, Premakeerthi had written so many songs. It was hard to escape the man’s lyrics. Harder to not grow to love them. Even harder to not keep on returning to them.

Lklyrics.com lists down around 80 songs written by him. A poor count. 1,000 would be a more exact figure, though even that can be contested. What’s more important than quantity, however, are the themes he returned to. To get to those themes, it is important to revisit the man’s life.

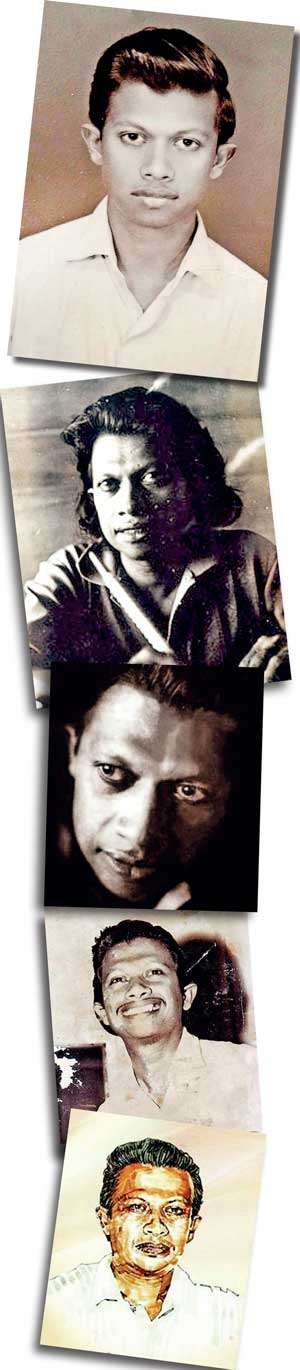

He was born Samaraweera Mudalige Don Premakeerthi de Alwis on June 1947 in Colombo. He was not born to an affluent family. His father was a railway employee. Educated initially at Maligakanda Maha Vidyalaya, he was sent to Ananda College, where he was engaged with the school magazine and other aesthetic activities that in turn got him to guide an entire generation of Anandians who would make their mark in arts, including Kularatne Ariyawansa.

Formative years

It was during these formative years that he encountered Karunaratne Abeysekara, aboard Lama Pitiya and Lama Mandapaya. More than his poetic skills, it was his voice that would win him audiences. With that voice came a yearning to join Radio Ceylon. He began working there from the latter half of the sixties, after a brief stint at the Dawasa Group (where he wrote feature articles). He became a full time announcer (he had been freelancing) in 1971, and was soon promoted as a programme producer.

When the radio gave way to the television in the eighties, he was eager to shift to the new medium, but found it a difficult route to tread, given that administrators were of the opinion that he did not possess the appropriate looks (especially with his less than awe-inspiring frontal teeth). But these misconceptions gave way, and he soon found himself presenting an array of programmes. A friend of mine recently tried to sum up his career in radio and television for me: “I have never heard a more perfect baritone Sinhala voice.” Wasantha Rohana, he suggested, came close. But only so close.

That was Premakeerthi the announcer. What of Premakeerthi the versifier?

Here are the opening lines to his first song, “Hada Pura Asune” (composed by Sanath Nandasiri, and performed by his wife Malkanthi and Rupa Indumathi).

හද පුද අසුනේ

සෙනෙහස බැඳුණේ

යුගයක පිය සටහන් මත්තේ

ජීවන මී බිඳු කඳුළක් වීලයි

ඔහු ළඟ ඔබ මෙන් මා ඇත්තෙ

Gunadasa Amarasekara wrote somewhere that the problem with the Colombo poets was their inability to go beyond certain clichés. In Mimana Premathilake’s poetry, which represents both rebellion against and affirmation of the kind of sentimentalised Victorian verses his contemporaries had swallowed, there is a blend of the risqué and the didactic, rampant with these same clichés, that outraged readers.

Over the years, after the debate over his verses had (almost) died down, a generation of versifiers imbibed the kind of language he resorted to, filled with the rhetoric of love, loneliness, and idealisation of the female figure. To me, the words “hada puda asune” and “jeewana mee bindu” represents that language, which Premakeerthi soon embraced and wielded. It was not the language of Sekara or even Ratnayake, of those versifiers who had started out as poets. To be sure, there had been versifiers who had transformed the rhetoric of love into a musical idiom. But it was Premarakeerthi who returned to the Colombo poets for this endeavour, and turned the undercurrents of torment and sorrow in their work into the popular song lyric.

At the same time, Premakeerthi (“Prem” to his colleagues) was not alone in what he was doing. Karunaratne Abeysekara, Ajantha Ranasinghe, and Sunanda Mahendra before him, and Kularatne Ariyawansa, Sunil Ariyaratne, and Ratna Sri Wijesinghe after him would idealise, if not romanticise, the village and make it more palatable to the dwellers of the city, in verse after verse. Almost all of them had come or would come from the press, as writers and journalists. Contemporary to a fault, they could not quite escape the fusion of the quatrain (“sivpadaya”) and free verse (“nisadas”) which even Mahagama Sekara had been entranced by. They were of the village, yes, but they had flirted with the city too, and its mosaic of art forms.

Creating own identity

What was unique about Premakeerthi was that, while he grew up in the company of these men, he carved his own identity. It was the poetry of love these lyricists resorted to, frequently. Premakeerthi resorted to that poetry too. But there was a difference.

Intensely personal, insanely poignant, his lyrics are, to me, the ruminations of a soul less concerned with the fact of love than its memory. If Ajantha Ranasinghe, whom I rate very high, wrote of loneliness tempered by the possibility of a brief encounter (“Paloswaka Sanda”, “Mage Lowata”, “Kunda Saman Mal”, and “Degoda Thala”), and if Kularatne Ariyawansa wrote of the possibility of a love that is requited after being rejected (“Aradhana”, “Seetha Arane”, “Sudu Muthu Rala Pela”, and his debut, “Pinibara Malak”), Premakeerthi, who followed the one and preceded the other, dwelt on neither acceptance nor rejection, but on the past.

For Ranasinghe, the past was the antidote that kept the hope of love alive. For Ariyawansa, it was a reminder of the ever omniscient possibility of rejection. For Premakeerthi, on the other hand, it was just what it was: the past, a repository of memories that was and is neither painful nor filled with happiness.

ඔබ අතගෙන

ගිය වීදියෙ

ඈ හා යනවා

සිඟිති පුතා

අතැඟිල්ලක

එල්ලී එනවා

Even at his most joyful, there is an undercurrent of sobriety, a reminder that the past is outside the reach of the lover who has lost and the lover who has reclaimed what he has lost. The future, and with it the possibility of reconciliation are what one can look forward to; they exist outside the periphery of the past. It is the “now”, and not the “hitherto”, in other words, that the versifier was concerned with.

සුළඟේ නලවා

පෙරසේ එනවා

ඔබ මා කළඹා

කිමදෝ යන්නෙ

නොරැඳී ගලා

When he let abandoned the rhetoric of love and, with Freddie Silva, took on society in the most didactic way he could, he retained this quality. The didacticism of a song like “Boru Kakul Karaya” and “Handa Mama” is firmly rooted in the present; the poet is less worried about past omissions than the situation his characters are in.

හඳ මාමා උඩින් යතේ

අපේ මාමා බිමින් යතේ

When Premakeerthi did resort to the past, it was to evoke memory, something which could never resurrect the present, so much so that we could only look back and say, “We can never reclaim it, but only regret it.” Consolation, for him, seemed to come from the present, the moment, and it compensated for everything else.

නොපිරුණු මේ

සිතට මගේ

ඔබ ගෙන එයි

සතුට අගේ

Our first real lyricists went to the wellsprings of our way of life, to evoke, and idealise, a rural arcadia which modernity would do away with. After them, we saw Mahagama Sekara, who, after wrestling with the present, and idealising the past, learnt (as “Maknisada Yath” showed) to accept that present.

The lyricists who followed these men were, for obvious reasons, caught up in an encounter between the hitherto and hereafter, and they found ways of tackling it. Memory, that most potent symbol of the past, figured in their verses. Premakeerthi had his own way of battling it: not by idealising it, nor by forgetting it, but by depicting it for what it was: a repository of the past.

18 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

17 Jan 2025 17 Jan 2025

17 Jan 2025 17 Jan 2025

17 Jan 2025 17 Jan 2025

17 Jan 2025 17 Jan 2025