The biggest challenge going forward is in preserving independence of the RTI Commission

An RTI workshop held in Baticaloa in progress

In the face of the global pandemic, information availability has taken the form of a pin in a haystack. But amidst

challenges, the implementation of the Right to Information Act No. 12 of 2016 has empowered citizens of Sri Lanka to ‘stand up against the state and ask questions.’ Today, Right to Information (RTI) has become a unifying thread among citizens from the North to the South. From sending a child to a school to disposing garbage to improving facilities in a hospital, the Act has played a role in giving a voice to their requests. However, experts are optimistic that the pandemic and certain Constitutional changes may not hinder a law that justified the expectations of people.

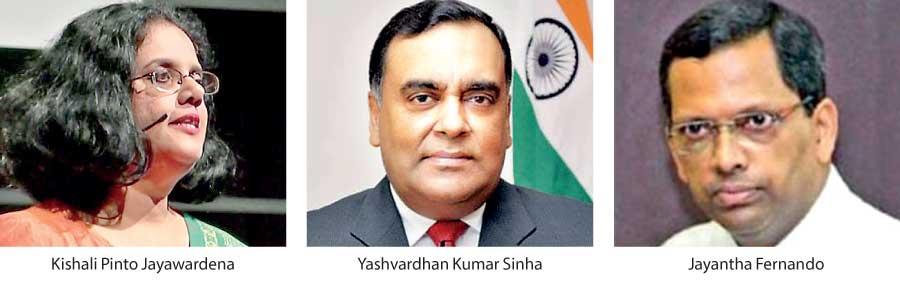

To discuss the gains of implementing the Act and what lies ahead, the Pathfinder Foundation and the Sri Lanka Press Institute jointly organised a webinar on Right to Information to mark World Press Freedom Day 2021 with the participation of a few experienced media personnel in Sri Lanka and India.

RTI as a tool to empower citizens

“Across the world, democracy and rule of law is on the retreat,” opined Kishali Pinto Jayawardena, Commissioner at the RTI Commission, Sri Lanka. “In Sri Lanka and other countries, the essentials of a democratic order, of a constitutional order that we have been held to observe as sacrosanct – an independent judiciary, responsible media and the constitutional separation of powers – are rendered nugatory in the current process and climate in which our countries operate. In other words, we are invited to think or believe that these norms are not essential for a functioning of a society or for a society to be prosperous and democratic. This is a problematic development we see around the world and in Sri Lanka as well. One of the reasons is a great failure in legal governance. There is a disconnect between the Constitution and what the law promises to deliver to citizens and what it actually delivers.

“So when reimagining RTI for Sri Lanka, the basic tool or objective was to look at RTIs as empowering citizens.

This was the primary purpose of RTI which we argued, advocated and struggled for Sri Lanka for 14 years. From 2003 onwards there was a RTI Bill before Parliament that was never passed and the process went on and on and ultimately in 2016 the RTI Act was passed. Despite enactment of the law not being broad-based - there were activists, lawyers, editors and journalists agitating and advocating for the information law - it is the ordinary citizens who have used the law, far more than media and civil society,” she continued.

Jayawardena further said that RTI has gone beyond asking for information and information release. “Empowering citizens to stand up against the state and ask questions is not something that we are used to after decades of conflict in the North and in the South – to ask questions from a police officer for example is problematic – but RTI has empowered people to do that. So the people have made the law central to their lives and their communities,” she added.

Independence of Commission threatened?

Speaking about challenges, she added that in the face of the global pandemic there were problems about meeting and discussing certain issues. “But we did have digital meetings and certain high technology avenues to overcome the problems. With the third wave hitting the current it has once again posed challenges – what do you do if an information officer is under quarantine, what do you do if public officials say that they didn’t have time to look into information requests as they were in lockdown?,” she questioned.

“Then there is the issue of resources. One of the weaknesses of the Sri Lankan RTI Act is the failure to provide adequate independent resources to the RTI Commission. The Act says that we get resources and funding through Parliament – what this practically means is that the nodal agency, the Mass Media Ministry funnels and channels money to the Commission. This is a big problem. It is a conflict of interest because, the Ministry, any ministry really, would be a public authority under the Act and subject to oversight of the RTI Commission. Therefore having a funding channel through a nodal agency to the Commission is a challenge.” she added.

“However, the biggest challenge going forward is in preserving independence of the RTI Commission. The law was drafted so that it setup an independent oversight agency that does not operate through executive fiat or executive will or pleasure. Members were appointed not solely through political appointments through the Executive bill but through a nomination process. There were civil society organisations making nominations, media and the Bar Association. It was the nominees from those organisations that were listed and then sent to the President who then made the appointments.

“The 20th Amendment last year basically vested all powers in the Presidency. So how would this affect the nomination of commissioners when the terms of current commissioners expire in September 2021? In Sri Lankan law the Commission has huge powers. The Commission has the power of prosecuting public officials when they don’t obey the Commission’s directives, power to determine in which cases information should not be released in the public interest override and so on. In Sri Lanka there are no agencies exempt from RTI Law. In all cases including public security, public interest can operate over and above to release information. It is the Commission that decides all these – the Commission delineates or defines the boundaries of what is public interest, gives guidance on public authorities on when they should use their discretion to release information.”

But let us be optimistic going forward. Certainly the law itself has justified the expectations of the people when it was enacted in 2016,” she said in conclusion.

RTI, Privacy and Data Protection

Since most of our information is freely available, there is a need to protect information while having a governing framework that would define that the information we give is protected and is processed by those who collect data. “Therefore, efforts were taken to formulate a Data Protection Bill and this came about during the early part of 2019,” opined Jayantha Fernando, Director – Sri Lanka CERT and General Counsel at Information and Communications Technology Agency (ICTA). “Article 14 (a) that sets the foundation for RTI in our Constitution also contains a privacy exemption which is manifested in Section 5 of the RTI Act. There have been many discussions as to how this will be reflected in the context of a law that will govern broad privacy rights.

“Privacy is a broad set of principles and data protection is a subset of those principles,” he explained. “During the drafting process we have imposed several obligations through this law on those who collect and process personal data who are deemed to be controllers and processors within the meaning of this draft bill. Controllers are those who collect data of all of us and this could be a private sector entity or even public authority and interestingly, the definition of a public authority in the Data Protection Bill captures the same definition embodied in the RTI Law.

“A whole new set of rights have been given referred to as ‘Rights of Data Subjects’ in the DPB and a Data Protection Authority has to be established for the proper governance of this law,” he continued. “This Bill will be applicable to those who process personal data where the processing of personal data takes place solely or partly in Sri Lanka, where the processing of personal data is carried out by a controller or processor who is in the country, who is an incorporated body in Sri Lanka or offers goods or services to data subjects in Sri Lanka including a specific targeting of individuals on FB, Google, Apple and all other entities including Yahoo and Whatsapp as well.

“This law supplements the RTI Act because the Act is recognised under the Data protection law as a means for lawful processing. Rights given through the RTI Act is supplemented through the provisions of the proposed Data protection bill. If larger public interest warrants disclosure then it would be deemed to be lawful, processing within Schedule I and II of the Data Protection Bill to provide such information relating to personal data that is required provided a proper balance is struck with regards to proportionality and necessity. Once the Data Protection Bill is in place, Data Protection Officers will have to be appointed in certain categories of institutions. The Data Protection Authorities will have to work with information officers appointed by the RTI Law to ensure a balanced application of both laws so that both laws would supplement one another and would not oust one another,” he observed.

Implementing RTI : The Indian experience

Speaking at the webinar, Yashvardhan Kumar Sinha, Chief Commissioner at the Central Information Commission, New Delhi, India spoke about the progress made with the implementation of the RTI Act of India. “Since its enactment in 2005, the Act has become a tool to show transparency and accountability and to combat the evils of corruption and nepotism. “Over 13.7 million RTI applications have been received in years 2019/2020 of which 10.8 million have been disposed of. In 2021 the CIC received 19,183 second appeals or complaints and have disposed 17,016 complaints. However, the pandemic has brought about how important it is that information is readily available for common man and citizens. In many cases people see RTI as a grievance addressing mechanism but it isn’t. But it turns out that in many cases it is an unintended grievance addressing mechanism,” he added.

Sinha however feels that the larger issue is in combating corruption. “One of the main issues is to get public authorities to conduct public transparency audits. “It’s normally done by a training institute attached to that ministry or department and authorities that do not have such institutes are permitted to go outside and get their institutions audited. A grading system is also in place and over the years, public authorities have been moving up the ladder in terms of this grading system and the public disclosures they make.” said Sinha. The grading system works as follows :

- Organisation and functions (10%)

- Budget and programmes (30%)

- Publicity and public interface (25%)

- E-governance (20%)

- Information that may be prescribed (10%)

- Information disclosed on public authority (5%)

In the face of the pandemic most hearings had to be done virtually and he believes that technological challenges will have an impact on how the RTI mechanism is being implemented. “A large number of video hearings had to be done during the pandemic. But a WhatsApp video would suffice if the appellant and respondent could be connected.” he said.

He also observed repetitive RTI applications and RTI applications that have been filed with an intention to harass another party. “Some applicants have filed more than 10 applications. This means people are proactive but you need to weigh your own right to ask questions and seek information against others’ rights.” said Sinha.

challenges, the implementation of the Right to Information Act No. 12 of 2016 has empowered citizens of Sri Lanka to ‘stand up against the state and ask questions.’ Today, Right to Information (RTI) has become a unifying thread among citizens from the North to the South. From sending a child to a school to disposing garbage to improving facilities in a hospital, the Act has played a role in giving a voice to their requests. However, experts are optimistic that the pandemic and certain Constitutional changes may not hinder a law that justified the expectations of people.

challenges, the implementation of the Right to Information Act No. 12 of 2016 has empowered citizens of Sri Lanka to ‘stand up against the state and ask questions.’ Today, Right to Information (RTI) has become a unifying thread among citizens from the North to the South. From sending a child to a school to disposing garbage to improving facilities in a hospital, the Act has played a role in giving a voice to their requests. However, experts are optimistic that the pandemic and certain Constitutional changes may not hinder a law that justified the expectations of people.