19 Oct 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

What makes Ravindra Randeniya stand out, what makes him, at the end of the day, Ravindra Randeniya, is his contemplative frown. You see that frown creep up everywhere, in almost every picture he’s in. It turns him, in varying degrees, into a meticulous detective, a pained lover, a mistrustful husband, even a compulsive trickster or conman or womaniser. The reason why he embodies all these characters, and their qualities, is because he’s so versatile; not the way Joe Abeywickrama or Tony Ranasinghe were, but in a less empathetic way. He is the only actor from here that I can think of who can frown in both a commercial and a serious movie and get away with it.

Randeniya is at his best, and his least empathetic, when he conceals his intentions with that frown. He is the great concealer, and is in fact so good at this role that nearly every other role is a variation of it. Not until the end of Duhulu Malak, the first real film he was in after supporting roles in a series of at best preparatory pictures, do we realise he is no more, and no less, than an irresponsible, prodigal playboy.

no more, and no less, than an irresponsible, prodigal playboy.

We think he’s such an unlikeable womaniser but he’s not. (At the very end he throws his shoe, in frustration, to the sea, and in that act he is both resentful and upbeat about the fact that he’s lost his woman.) What conceals those intentions is his sense of debonair grace, which is so debonair that he can hide the vilest intentions of his characters with his charm.

That explains why Maya, Dadayama, Sagara Jalaya, and Anantha Rathriya work so well when he’s around: he’s so good at talking, at faking, but we believe him along with the (for the most) female protagonists, who in all these movies happened to be Swarna Mallawarachchi. When Rathmali from Dadayama has her illusions about the man who impregnated her twice and left her shattered, she threatens him and writes him a letter; when they meet the next time, he is flippantly ominous about her missive: “Who are you to post letters ordering me? Who are you to boss me around?”

In the sequences that preceded this encounter, however, he is so charming, so apologetic about what he’s done to this woman, that both Rathmali and the audience know that she has every right to be intimidating and threatening towards him: because of his debonair grace he’s become a part of her, and all those dreams of hers about him are derived from that quality of his.

"Randeniya is at his best, and his least empathetic, when he conceals his intentions with that frown. "

Because he can be two people at the same time – sometimes for the better (as with Chuda Manikye, Siripala Saha Ranmenika, and to a certain extent, Sagara Jalaya), and often for the worst (Dadayama, Bhava Duka and Bhava Karma, and Roy de Silva’s Sudu Piruvata) – people choose to believe in the latter, which more or less indicates that we’re cynical enough to be swayed by villains. But Randeniya is not only a villain, though in the he was so typecast that he was thought fit to play no one else. In Vijaya Dharma Sri’s Aradana, which was almost a Dadayama turned the other way around, yielding a happy resolution and ending, he goes after the woman he befriended (Malini Fonseka) to reclaim her. There’s a Ravindra Randeniya that exists beyond all this too.

He was born Boniface Perera in Dalugama, Kelaniya on June 5, 1945 to a successful mudalali family. A self-made businessman, his father initially put his son into St Francis’s School, run by the Dalugama Church. Two years later, he was admitted to St Benedict’s College, Kotahena. This is where he was initiated into his first love: literature. His tastes at the time – Martin Wickramasinghe with Gorky,

Dostoyevsky, and Chekhov – wildly diverged from those of his classmates, who preferred easier-to-digest pulp fiction from that era and teased him for his own preferences. It was a largely vernacular backdrop which greeted him at St Benedict’s, despite the fact that it was, all in all, a missionary school. “There was only one period for English,” he remembered for me, “During all other periods, we talked freely in Sinhala, though we had Tamil and Burgher and even Muslim friends. Race and religion didn’t matter. Not to us.”

What he read, he remembered, had for some time turned him into a leftist: “Everyone’s a socialist at 20!” was how he reflected on it for me. Surprisingly though, none of these encounters got him to act. Apart from a Fifth Standard production of Sigiri Kashyapa, in which he was Kashyapa, he never acted at all. His first real initiation into his profession would therefore come from an outsider:

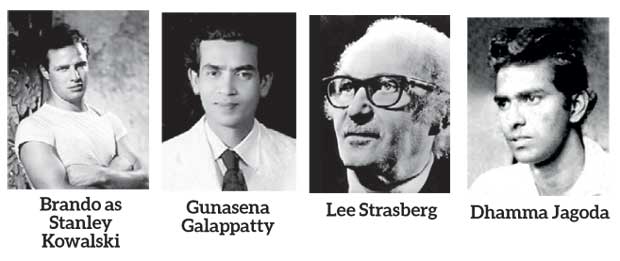

Dhamma Jagoda, who with Sugathapala de Silva was openly spurning Ediriweera Sarachchandra’s stylised conception of the theatre. One thing led to another, and soon enough, he was studying at the Lionel Wendt Theatre Workshop, which Jagoda had founded after returning to Sri Lanka from an American tour. “He brought Method Acting to this country, in fact. He had been to the Actors’ Studio, he had met Elia Kazan and Strasberg, and he had seen Marlon Brando.”

Jagoda had taken it upon himself to preach Strasberg’s gospel in the country, and Randeniya had obviously come under his influence. He had not, however, entered the Workshop to study acting at all, rather screenwriting, directing, stage decor. “Somehow or the other, I found myself in an acting class. I had by this time been drawn to the whole idea of becoming a performer, instead of remaining backstage.

That was also a common class: whether or not you had chosen the subject, you had to attend it for at least one or two hours.” The course lasted for two years, and Randeniya found himself being dragged into various roles and performances. His first production as such had been Gunasena Galappaththy’s Muhudu Puththu, controversial for its time owing to its depiction of adultery, but a culmination of sorts to everything he and his colleagues had learnt.

Muhudu Puththu had been a success; among those who thronged that night at the Wendt was the filmmaker and the iconoclast, Manik Sandrasagara, who after congratulating Randeniya’s performance insisted on taking him to his first movie, Kalu Diya Dahara (1970). Kalu Diya Dahara was another success; having watched it and been impressed by his portrayal of an estate labourer, another filmmaker came around, congratulated him, and took him aboard his next film.

The director was Lester James Peries, the film, released two years later and lukewarmly received, was Desa Nisa. No two directors could have been more different. Randeniya himself was warm about both: “Manika had a way of asserting himself. Dr Peries never asserts himself. In fact you never feel that he’s there overseeing you.” In Desa Nisa he was a morally ambiguous hermit, able to restore sight or stunt it at his will. It was followed by Duhulu Malak (1976), another hit.

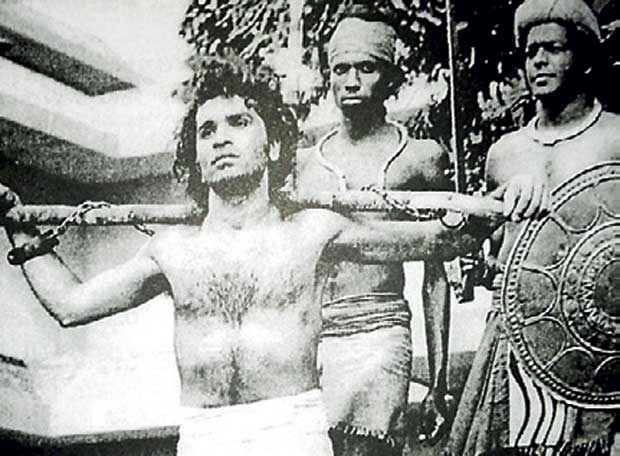

None of these movies really “awakened” the thespian in him. That would come a year later, in 1977, with Amaranath Jayatilake’s Siripala Saha Ranmenika, where he starred for the first time opposite Malini Fonseka and which took him back to a role which would creep up in the years to come: Samson, the Sinhalised version of Stanley Kowalski, from Ves Muhunu, Dhamma Jagoda’s adaptation of A Streetcar Named Desire. “To become Siripala I had to become bestial, almost inhumane. It was the same story with Samson.

” When we were young we were horrified when Kowalski (Samson, by the way, had first been portrayed by Jagoda himself, in 1963) jeers at Blanche DuBois; when we grew up, we realised that it was his way of asserting the truth, that Blanche was, in fact, a pretender, and that her gentility never rubbed off on an animalistic brute like him. It was that kind of animalistic brute, who never cares for affection and never even once feels sorry for anyone other than those who are closest to him – he doesn’t even care for himself – which is embodied in his subsequent, villainous performances.

That they  are among the best of their kind indicated, quite clearly, that he had found his signature.

are among the best of their kind indicated, quite clearly, that he had found his signature.

There were of course other characters, other films: as Migara in The God King (1975); as a modern-day Rama in Sita Devi (1978); as the hero in Weera Puran Appu (1979); as the brother-in-law of Swarna Mallawarachchi in Sagara Jalaya (1988); as the troubled protagonist in Anantha Rathriya (1996), as the nouveau rich mudalali Lionel in Wekanda Walawwa (2005). In the first three movies he’s a beleaguered hero, and in the latter three he’s a beleaguered antihero.

In Weera Puran Appu, which was made as an epic that dwelt on sharply and clearly defined heroes and villains, he was clear, concise, and direct. But as the cousin in Sagara Jalaya, by contrast, he leaves us in the dark.

And what makes this sense of indirectness, obliqueness, is that we are never entirely sure as to whether he’s going to stick to his word: he’s a talker, a consoler, but also a concealer. With one set of characters he’s a different man. (You see this in Dadayama, where to his fiancée, played by Shirani Kaushalya, he is the perfect lover; he is anything but to the woman he impregnates, who demands at the end that he suffer for what he’s done to her.) It’s a call for condemnation, and his Priyankara Jayanath is so despicable that Regi Siriwardena, in an otherwise laudatory review, called him “a solid, if less complex, character portrayal.” That was who his villains were, at the end of the day: solid, despicable, hateful, and one-dimensional. What made them all multidimensional and stand out, as I observed before, was that deceptively contemplative frown.

20 Dec 2024 5 hours ago

20 Dec 2024 6 hours ago

20 Dec 2024 7 hours ago

20 Dec 2024 8 hours ago

20 Dec 2024 9 hours ago