23 Apr 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

There is also the possibility that many have evaded arrest and police patrols, thus remaining unrecorded

People who face such vulnerabilities need systematic remedies that include tools and resources as measures to guide their behaviour

The second week of March brought with it the tragic spread of the Corona Virus. A month of careful planning and concentrated action have allowed Sri Lanka to control the spread of COVID-19, limiting its worst to 5 out of 25 districts.

|

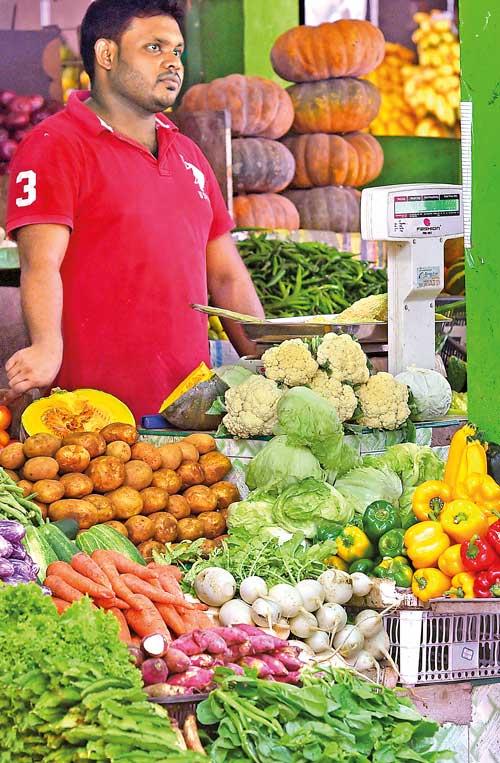

The worst hit in the economy during this pandemic are those earning daily wages |

Even though these districts are still under tight scrutiny and control, and the country is in lockdown, the general sense of the people seems to be optimistic and the government’s actions have received some praise. However, on April 18, a relaxation of the lockdown measures was declared. This could have many repercussions with people unable to return to normalcy.

It is indubitable that the country’s economy has come to a halt due to the virus. The worst hit in the economy are those earning daily wages. The situation could lead to national and international economic downfalls. This article highlights two incidents that result in social vulnerabilities, which could benefit from careful national attention.

Pandemic paranoia

Unique characteristics can be identified in a society facing a severe epidemic. Over a two-month period, incidents of exploitation and fear-driven behaviours can skyrocket, especially among small groups of communities and individuals. Such occurrences negatively impact the social order. If the objective of the universal social policy is meeting social wellbeing and the status quo, social relations are meant to create orderly behaviour. However, this situation changes in a pandemic situation. People who cannot access the services they need on a daily basis and people whose movements and daily activities are restricted will find that they face psychological and physical vulnerabilities.

Additionally, a lack of access to resources leads to social vulnerabilities. Beginning in pockets of communities, they can even multiply until it becomes a national occurrence. Over time, psychological vulnerabilities will surface from the latent stage to a visible stage. According to many reports on the subject, an epidemic can result in a high perceptional risk among people. This was mirrored in Sri Lanka, where the first case of a local patient being discovered in the country resulted in fear and panic. It also led to a stigmatising of daily routine activities.

The confluence of emotional and environmental elements lead to fear and frustration that can, in turn, lead to disorderly behaviour, which can cause harm to the social order. Some of this behaviour is unique to the situation. Over the past few weeks, some people who were quarantined refused to be quarantined and fled those centres. Some others, who returned from countries with large numbers of infections and who were already infected, refused to disclose their status, thus putting many people at risk. Such behaviour abuses general law provisions. In addition, some engaged in unethical business practices: black market selling, price hikes, middlemen conspiracies, and fake food shortages. These types of malpractices can result in a weaker social system prone to social abuses. Thus, crime, theft, injuries, and abuses driven by fear and frustration cannot be far from a society thus weakened.

Disorderly behaviour

The occurrence and reoccurrence of such vulnerabilities can only bring disorganization and chaos to the society. In such societies, although punishable by law, the people might feel no fear or guilt about engaging in disorderly behaviour such as transporting of illegal substances, manufacturing of illicit liquor, domestic violence, child abuses, robberies, physical clashes, and even aggressively disobeying public health rules. There appears to be much societal risk and fear-induced behaviour in society and many such incidents were recorded in Sri Lanka. Police reports point out that curfew violations in the month from 20th March to 20th April exceeded 30,000 people with 8,000 vehicles being impounded. This is a considerably high number, especially given the repeated announcements in the media and through many other methods. There is also the possibility that many have evaded arrest and police patrols, thus remaining unrecorded. Although as yet unrecorded, incidents of domestic violence are expected to spike, according to psychosocial experts who warn of the possibility among all communities irrespective of whether rural or urban and all ethnic groups. It is also interesting to note that such incidents mostly occur among the poor or those who engage in similar conduct during ordinary times. The reason for detection could be that the emergency situation requires heightened patrolling.

People undertake disorderly conduct because of the multiple vulnerabilities they labour under. These people can be less educated and poverty-stricken, as well as shameless and fearless. They may have little support from their families. In Suduwella, Ja-Ela, all those who were affected by COVID-19 are addicted to drugs. People who face such vulnerabilities need systematic remedies that include tools and resources as measures to guide their behaviour.

Sudden livelihood collapse

Another dimension of these vulnerabilities is livelihood collapse. As mentioned above, the poor are worst hit during such situations. Those engaged in earning daily wages, such as labourers, labourers’ assistants, retail businessmen, ordinary village farmers, and many others attached to cottage industries, will bear the brunt of the results. The situation requires an analysis that goes deeper than the surface-level. According to the 2013 World Bank report, 45% of Sri Lanka’s population earn less than US$5 a day, and this situation remains largely unchanged. The country’s main revenue sources are foreign remittances, tourism, port services, and telecommunication services. Three of these four industries have been affected by the pandemic, which thus negatively impacts the economy. The country will need to completely overhaul and revitalise plans for income generation if it is to return to its previous trajectory.

Additionally, the Government must bear in mind the vulnerabilities that spring from income-related vulnerabilities. People are prone to injustice, discrimination, and emotional manipulations based on the frustration and anxiety they feel. Many have spoken out against the financial scheme proposed by the government to provide Rs. 5,000/- to the poor, namely senior citizens, Samurdhi beneficiaries, people with disabilities, and kidney patients. Although the recipient lists have been revised to include more communities, it is highly unlikely that the proposed amount was properly disbursed to the needy or that the money provided sufficient relief. Economic vulnerabilities can be identified in occupation groups too. Those engaged in fishing, tailoring, handicrafts, and carpentry industries as well as agriculture are beginning to face economic constraints. As they are not considered as belonging in the “poor” category, they are not entitled to the assistance of Rs. 5,000. However, they declare losses in production/yield and disconnected networks and business partnerships, both of which impact their ability to generate revenue.

They will need to face large costs in financial terms as well as in time and space to regain from these structural burdens. Thus, they require more than simple conflict mitigation measures and relief bundles.

All of these evidences point to how the pandemic will disproportionately influence the communities that require a larger social focus. This article provides an opening to a deeper discussion on the identified and related matters, and calls for a detailed and well-thought out national plan. The government will need to invest in research and policies based on facts to mitigate the issues that the pandemic has brought on, if we are to create an economic renaissance in Sri Lanka.

The author is currently attached to Department of International Relations, University of Colombo. She was a Consultant at Sri Lanka Institute of Development Administration (SLIDA) from 2009-2018.

28 Nov 2024 44 minute ago

28 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 3 hours ago