11 Dec 2018 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

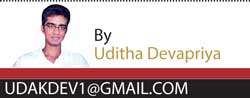

In February 1835, the historian, politician, and imperialist Thomas B. Macaulay in a well received address known today as the Minute on Indian Education urged the then Governor General of India,William Bentwick, to reform secondary education in the country so as to deliver “useful learning.” Colonial policy until then had been one of conciliation, of funding places of learning to promote native languages (especially Persian and Sanskrit). Ever since Warren Hastings’s term as Governor General, it had been recognised and taken for granted that to obtain the loyalty of the native subjects, it was necessary to make concessions to them.

In February 1835, the historian, politician, and imperialist Thomas B. Macaulay in a well received address known today as the Minute on Indian Education urged the then Governor General of India,William Bentwick, to reform secondary education in the country so as to deliver “useful learning.” Colonial policy until then had been one of conciliation, of funding places of learning to promote native languages (especially Persian and Sanskrit). Ever since Warren Hastings’s term as Governor General, it had been recognised and taken for granted that to obtain the loyalty of the native subjects, it was necessary to make concessions to them.

But by the time of Macaulay’s ascent in British India, Britain was undergoing a transformation. Macaulay belonged to the Whig faction of the Conservative Party, which stood for the interests of industrialists. Between 1815 and 1846, the campaign of these industrialists was the abolition of the Corn Laws. This pitted them against the traditional elite, the farmers. The Whigs, in their support of the industrialists over the aristocracy, espoused a utilitarian philosophy: they judged everything by its use, and whether it promoted the maximum happiness of the maximum number of people. Put simply, they measured everything in terms of returns and profits.

Dickens would lampoon and ridicule the Utilitarian in Hard Times:

A man of realities. A man of facts and calculations. A man who proceeds upon the principle that two and two are four, and nothing over, and who is not to be talked into allowing for anything over. With a rule and a pair of scales, and the multiplication table always in his pocket, sir, ready to weigh and measure any parcel of human nature, and tell you exactly what it comes to. It is a mere question of figures, a case of simple arithmetic.

At the same time, Utilitarianism became the secular expression of an evangelical movement that found its footing in the heat and dust of India. As the authors of The Great Indian Education Debate put it, it was an alternative vision of the Empire that challenged the likes of Hastings, who had stood for a policy of conciliation and had stood behind the school referred to today as the Orientalism.

The first person to openly challenge and spurn Hastings and the Orientalists was Charles Grant, who had served twice at the British East India Company (1768-1771 and 1774-1790) and who was a prominent member of the evangelical movement. In 1776, two years into his second tenure, he underwent a religious conversion that led him to oppose the upholding of Indian traditions. He enunciated his views in a book published in 1821, Observations on the State of Society among the Asiatic Subjects of Great Britain, which indicted the British for being no better than “passive spectators” of the “unnatural wickedness” in the faiths adhered to by Indians. The solution he proposed was simple: introduce the natives to Western learning.

Translated to official policy, this meant educating the natives on what were perceived to be the significant and enlightened aspects of British rule, in particular the language of the ruler. As Macaulay stood in 1835 and delivered his verdict on this controversial issue, he made a remark that has been endlessly quoted since:

We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern – a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect. To that class we may leave it to refine the vernacular dialects of the country, to enrich those dialects with terms of science borrowed from the Western nomenclature, and to render them by degrees fit vehicles for conveying knowledge to the great mass of the population.

There were two aspects to this new education policy, and they stemmed from his belief that subjects of colonial rule needed to be Anglicized. At the same time, he did not believe in Anglicizing every native. It was directed instead at a class of people who would be nurtured to “be English” in everything but the colour of their skin, and who would convey Western ideas to the mass of the population. The teaching of English was one route through this class could be created; another route was Christianisation, though Macaulay stood for a policy of religious neutrality. (His contention was that abstaining from the conversion of native Indians did not mean expiating “monstrous superstitions” such as the killing of goats.)

How would this be “useful”? Consider that until then, several institutions had been established by the British, at their cost, to educate the natives on their own languages. These included the Calcutta Madrasa, established in 1780; the Fort William College, established in 1800; and the Sanskrit College, established in 1824. Contrary to usual practice, students didn’t pay for their education; they were instead paid a stipend to learn the languages, and to this end, funds were allocated for the translation of key Sanskrit, Urdu, Hindi, Arabic, and Bengali texts to English.

Macaulay’s argument, in keeping with the Utilitarianism in vogue in England at the time, was that this rebelled against basic principles of political economy. What people find useful, he reasoned, they would gladly pay for. Or in his words, “What we spend on the Arabic and Sanskrit Colleges is not merely a dead loss to the cause of truth. It is bounty-money paid to raise up champions of error.”

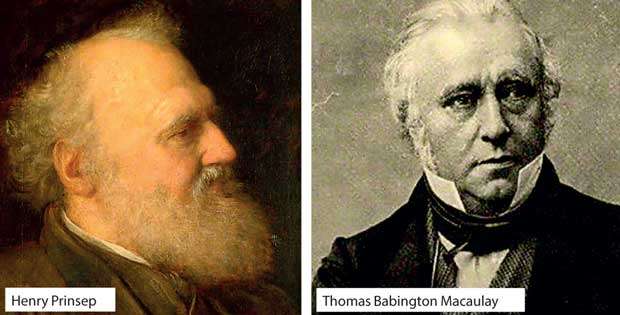

With such a point did he triumph against the Orientalist “educationists”, the most prominent of whom, Henry Prinsep, defended the old policy on the basis that it was rooted in not just the South Asian tradition but the Western tradition as well. The Orientalist argument here was that Western seats of learning had been financed by grants which did not always generate returns. What Prinsep did not know, however, was that Macaulay had criticized the funding of such institutions on home soil: some years before, he had attacked the endowments which supported the study of Greek, Latin, and mathematics at Cambridge University.

The tide, in any case, was against Prinsep.Macaulay won the debate; the Minute had vindicated him. The debate had been put in place to question the merits of the English Education Act of 1835. With Macaulay’s speech, the Act was quickly enforced, and the result, as historians have noted, was that vernacular education, while not stifled or deprived of funds, received little, if at all any, attention from the Company.

The effect of this was to reduce British intervention in the education of the masses; schooling remained for decades the preserve of the elite, the class which Macaulay had baptized. How adversely this affected India can be gleaned by what Will Durant observed in his seminal work.

The Case for India: There are now in India, 733,000 villages, and only 162,015 primary schools. Only 7% of the boys and 1.5% of girls receive schooling, i.e. 4% of the whole. Such schools as the Government has established are not free, but exact a tuition fee which, though small to a Western purse, looms large to a family always hovering on the edge of starvation.

There were two aspects to this new education policy, and they stemmed from his belief that subjects of colonial rule needed to be Anglicized. At the same time, he did not believe in Anglicizing every native

It comes to no surprise that investments in education were severely lacking: The total expenditure for education in India is less than one-half the educational expenditure in New York State. In the quarter of a century between 1882 and 1907, while public schools were growing all over the world, the appropriation for education in British India increased by $2,000,000; in the same period appropriations for the fratricide army increased by $43,000,000.

Or in other words, at a time when the Government was spending 83 cents per head on its army, it was spending eight cents per head on education. As far as the Utilitarian-evangelical argument went then, the experiment was a failure; “useful education” had, in the end, become a mere exercise in exploitation, poverty, and ignorance.

What was even more significant was that this spread out to other parts of the Empire, most notably Sri Lanka. Six years before Macaulay made his speech, a Commission had been tasked with the object of proposing reforms. Among the recommendations made by this, the Colebrooke-Cameron Commission, were the abolition of the free compulsory scheme of labour known as rajakariya, the establishment of an Executive Council and Legislative Council (where members would be selected, not elected), the amalgamation of the Maritime and Kandyan provinces as a single administrative unit, and the admission of Ceylonese into the Civil Service. As Patrick Peebles has noted, while these recommendations were endorsed by the Governor, most of them “were never implemented or weakened over time.”

In one area, however, they were adhered to: the need for an education policy. That the Colombo Academy, the first public school in the country, was established in 1835, the same year in which the English Education Act was passed in India, couldn’t have been a coincidence. As I will make clear in the next essay, while the schools policy of the British in Ceylon was not exactly in concert with trends in colonial education policy in India, there were recurrent parallels between the two. When you consider that both Colebrooke and Cameron had been in British India, at the Company, and had come under the growing influence of the Utilitarians (or the “Anglicists” as some call them) over the Orientalists, you will realize that in part at least, British education policy in Ceylon followed, if not imitated, the policy of the British Raj.

The author can be reached on [email protected]

30 Nov 2024 5 minute ago

30 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 5 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 6 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 9 hours ago