28 Sep 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A few months ago, I saw an advertisement in a local newspaper regarding a motor championship which fascinated  me: Eliyakandha Hill Climb. Eliyakandha – for the latecomer – is the local name for Brown’s Hill, a steep climb not far from the sea in Matara. Long before this motor race, Eliyakandha’s call to fame was owed to a notorious military-run torture camp complex situated there during the state’s crackdown of the 1987-90 rebellion. The camp itself was run in an old manor-type house to which an elite family in the area had claimed. In its hay day, the persons brought to Eliyakandha were mostly destined to die. So, the torture camp was also called K-Point, or Killing Point.

me: Eliyakandha Hill Climb. Eliyakandha – for the latecomer – is the local name for Brown’s Hill, a steep climb not far from the sea in Matara. Long before this motor race, Eliyakandha’s call to fame was owed to a notorious military-run torture camp complex situated there during the state’s crackdown of the 1987-90 rebellion. The camp itself was run in an old manor-type house to which an elite family in the area had claimed. In its hay day, the persons brought to Eliyakandha were mostly destined to die. So, the torture camp was also called K-Point, or Killing Point.

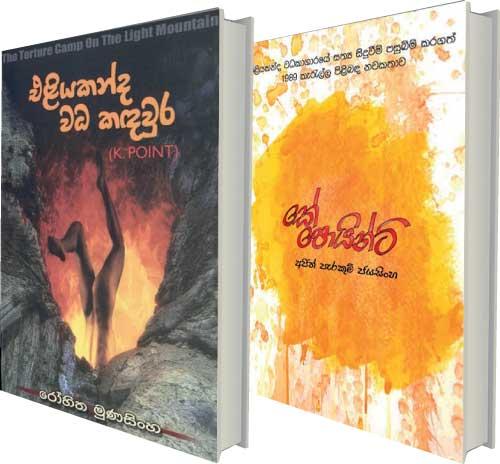

The advertisement about motor cars racing up and down Eliyakandha hill reminded of two books written about the camp by two men who were tortured there but survived the ordeal: who, among hundreds of others, had endured the shattering experience of torture, reduction, and humiliation, to come out alive and take courage in writing down their tales. One is Rohitha Munasinghe – a pioneer of sorts in survivor literature emerging from the 1987-90 violence. His “Eliyakandha Wadha Kandhawura” (2000) is a harrowing story of unimaginable torture being carried out in the guise of counter-insurgency. I do not wish to go into details. It is sufficient to note that after reading some of its passages you can watch (without flinching) any horror movie.

The advertisement about motor cars racing up and down Eliyakandha hill reminded of two books written about the camp by two men who were tortured there but survived the ordeal: who, among hundreds of others, had endured the shattering experience of torture, reduction, and humiliation, to come out alive and take courage in writing down their tales. One is Rohitha Munasinghe – a pioneer of sorts in survivor literature emerging from the 1987-90 violence. His “Eliyakandha Wadha Kandhawura” (2000) is a harrowing story of unimaginable torture being carried out in the guise of counter-insurgency. I do not wish to go into details. It is sufficient to note that after reading some of its passages you can watch (without flinching) any horror movie.

A particular reference Munasinghe evokes has stayed etched in my mind: that of military vehicles (trucks and jeeps) moving up the steep Eliyakandha hill in “first gear”. It is a sharp climb for the heavy vehicles and – on different occasions – we encounter these jeeps coming and leaving the torture premises as they bring to the house of organized death high officials, newly abducted prisoners and food cauldrons.

The coming of these vehicles usher an ominous suspense. When they leave, they take away prisoners to be killed,  or the crudely packed bodies of already killed men. In a different era, it was a different hill climb.

or the crudely packed bodies of already killed men. In a different era, it was a different hill climb.

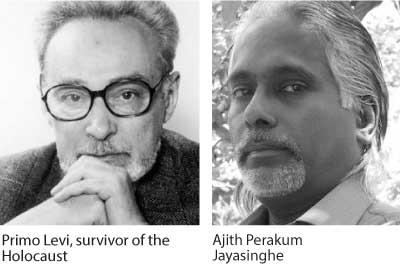

A second Eliyakandha survivor narrative was published in 2018 by Ajith Perakum Jayasinghe, a reputed blogger and social commentator. Written as an autobiographical novel, Jayasinghe’s “K-Point”, in many instances, confirms the depravity and bestiality unfolding in Munasinghe’s recollections. But, Jayasinghe’s goes beyond than being a mere retrospection to show a mature mind at work, as he reconstructs a past horror with reasonableness and revision. The preface to “K-Point” suggests that Jayasinghe has reconciled with the injurious past. His, in fact, is one of the most profound reassessments I have read by a violated person in characterizing his persecutor. Dismissing the conventional binary reading of victims and victimizers, Jayasinghe proposes that, in the torture camp of 1987-90, there were only victims: victims defined by the political crisis of the time.

Both Munasinghe and Jayasinghe write in Sinhala (a translation of “Eliyakandha Wadha Kandhawura” exists, but it is too weak a work to take us far). They are merely two icons of an emerging floor of survivor narratives from Sri Lanka’s proud histories of civil conflict: from 1971 to times post-2009. But, how rarely – if at all – are these survivor narratives meaningfully incorporated with our curriculum? We are living in an age where our award-winning poets themselves tire us with long essays admonishing the need for responsibility and justice. It is more fascinating than the hill climb advertisement that a post-conflict society (which parrots for the right season the right buzz words in reconciliation) takes no serious interest in survivors and their stories. These are the narratives that humanize the atrocity of conflict, drawing our imaginations and emotions to reassess the misplaced glory in the systematic taking of human lives.

Reconciliation, in part, entails overreaching private feelings and your reading of conflict from within your limited situation. It stems from a nurtured capability and a desire to reach beyond personal loss to understand an event with empathy. This is why survivor narratives are important for a post-conflict society: they propose necessary energy that can heal, and transform our collective vision to imagine, in humanistic terms, beyond the petty.

Reconciliation, in part, entails overreaching private feelings and your reading of conflict from within your limited situation. It stems from a nurtured capability and a desire to reach beyond personal loss to understand an event with empathy. This is why survivor narratives are important for a post-conflict society: they propose necessary energy that can heal, and transform our collective vision to imagine, in humanistic terms, beyond the petty.

Holocaust survivor Primo Levi writes about what he calls “warning monuments”: leftovers relics of a conflict that reminds society of atrocity and violence. In 1944 and 1945, Levi was a prisoner at Auschwitz-Birkenau. His torture camp story is told in “If This Is a Man” (1958). Levi’s suggestion to preserve the memory of violence is a noble thought that, at present, is very far from Sri Lanka. In Sri Lanka, we are indifferent to the violated and have no remorse over such violence. Sites of demonic conduct are easily forgotten once their walls are re-painted, and are easily converted into the finishing line of a motor race. Enforced death has been such a banal occurrence – and indeed an integral part of political strategy – that our response to survival is skewed.

But, literature begins with ideals, morals, and human foibles. In other words, the true literature is in these narratives that we shut out of our classrooms. True reconciliation cannot be had in denial or with matters under the carpet. Perhaps, it is time to re-work what our children should (also) read as they grow to be responsible and empathetic women and men.

27 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

27 Nov 2024 5 hours ago

27 Nov 2024 5 hours ago

27 Nov 2024 6 hours ago

27 Nov 2024 6 hours ago