31 May 2021 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

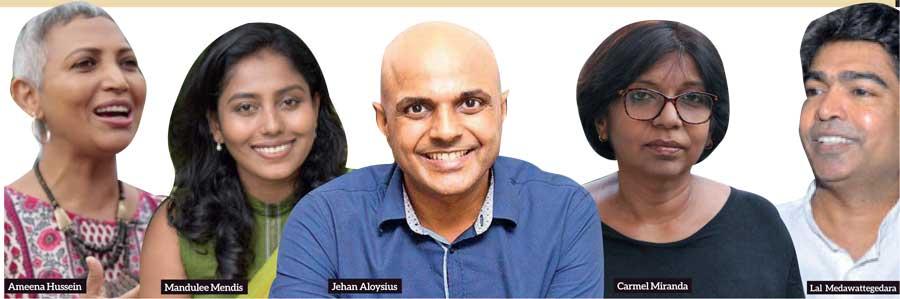

On the evening of April 5, the shortlist of the 28th Gratiaen Prize was announced by judges Ashok Ferrey, Mahendran Thiruvarangan, and Victoria Walker. From a short long-list of eight entries that had earlier been announced, two novels, a short story collection, a creative travelogue and a play were shortlisted for what some consider as the “Sri Lankan Booker”. Out of Mandulee Mendis’ “Red Brick Wall”, Lal Medawattegedara’s “Restless Rust”, Jehan Aloysius’ “Mind Games”, Carmel Miranda’s “The Crossmatch”, and Ameena Hussein’s “Chasing Tall Tales and Mystics: Ibn Batutta in Sri Lanka”, one title is en route to Gratiaen glory in the final that has been scheduled for 9 June.

Mahendran Thiruvarangan, and Victoria Walker. From a short long-list of eight entries that had earlier been announced, two novels, a short story collection, a creative travelogue and a play were shortlisted for what some consider as the “Sri Lankan Booker”. Out of Mandulee Mendis’ “Red Brick Wall”, Lal Medawattegedara’s “Restless Rust”, Jehan Aloysius’ “Mind Games”, Carmel Miranda’s “The Crossmatch”, and Ameena Hussein’s “Chasing Tall Tales and Mystics: Ibn Batutta in Sri Lanka”, one title is en route to Gratiaen glory in the final that has been scheduled for 9 June.

Even though Chamanthi Denisha Jayaweera, Megan Dakshini and Piumi Wijesundara – in that order, the authors of “A Sunbird’s Guile”, “Softly We Fall”, and “Ovaryacting” – were eliminated from the competition at the long-list stage, it by no means dilutes the intensity of a star-studded final cast of whom some are epoch-defining creative practitioners of this generation. While Ameena Hussein has been a former finalist in 1999 for her highly acclaimed short story collection “Fifteen” – in my view, Hussein’s best work between 1999 and 2020 – Jehan Aloysius, for, “Screaming Minds”, was a shortlisted author in 2000. Earlier in 2020, in a review of her poetry collection “Me and My Saree” (2019) – while drawing attention to the promise I saw in her writing (to be), only if she could go beyond what I called ventriloquism – I marked in Mandulee Mendis’ writing a lack of originality and conviction. Her berth in the shortlist for “Red Brick Wall” seems an apt response to her critic; and a good enough reason for me to await the book’s publication. The other deep footprint in the final pentagon is that of Lal Medawattegedara: shortlistee in 2002 for “The Window Cleaner’s Soul” and the winner in 2012 for the deeply engaging “Playing Pillow Politics at MGK”. From what has been said about it so far, “Restless Rust” – an unpublished manuscript – seems to hold as much promise as “Playing Pillow Politics” for innovative form and thematic engagement. But, that is for the future to see.

Quite disheartening, however, is the abysmal media interest in the shortlist that rarely – if ever – spread beyond the generic announcement which, in all likelihood, was obtained from the Gratiaen Trust itself. A dearth of passion and drive to produce original research or unearth news that would engage the interest of the world has dulled most reporting of the shortlist in mainstream media. It could be that some media institutes are saving the best for last. But, that would be another dance in another hall. Being a meeting place of Titans, there are statistics, observations, trivia, and references without which a report on the event is hardly complete: a necessary supplement which is deprived of the arts enthusiast.

"Some award-winning English writers – to mollify the displacement they feel in literary platforms organised by the Sinhala literati – have a dirty habit of apologising out loud by placing Sri Lanka’s English creativity as a pseudo domain"

Almost at the end of its third decade as the trustee of Sri Lanka’s most reputed literary prize, the Gratiaen Trust has a policy not to recall a once utilised judicial resource to its bench. As such, an appointed Gratiaen judge – for better or for worse – has one term and a single sentence to pronounce. While, at one end, this prevents some of the leading figures in the trade – such as, for instance, Nihal Fernando and Arjuna Parakrama who (as it can be expected) had already judged the prize a quarter of a century ago – at the other end, it democratises the judging space for people like Victoria Walker to preside over our post-Victorian predilections. Ashok Ferrey, a shortlistee in 2002, 2006, 2012 and 2015 – the only Gratiaen shortlistee to be shortlisted under two pseudonyms – brings in a unique feather to the panel by being one of the few Sri Lankan writers to have almost all of his work published regionally, in India.

Almost at the end of its third decade as the trustee of Sri Lanka’s most reputed literary prize, the Gratiaen Trust has a policy not to recall a once utilised judicial resource to its bench. As such, an appointed Gratiaen judge – for better or for worse – has one term and a single sentence to pronounce. While, at one end, this prevents some of the leading figures in the trade – such as, for instance, Nihal Fernando and Arjuna Parakrama who (as it can be expected) had already judged the prize a quarter of a century ago – at the other end, it democratises the judging space for people like Victoria Walker to preside over our post-Victorian predilections. Ashok Ferrey, a shortlistee in 2002, 2006, 2012 and 2015 – the only Gratiaen shortlistee to be shortlisted under two pseudonyms – brings in a unique feather to the panel by being one of the few Sri Lankan writers to have almost all of his work published regionally, in India.

Other than the one-off rule on judges, the “Sri Lankan Booker” is also yet to produce a JM Coetzee: a writer with a Gratiaen double (Coetzee won the Booker Prize twice, for “The Life and Times of Michael K” and “Disgrace” in 1983 and 1999). Therefore, Medawattegedara’s inclusion in the last five should be of statistical interest for the aficionado. Previously, Neil Fernandopulle (winner 1999 in 2004), Sumathy Sivamohan (winner 2001 in 2007), Vivimarie Vander Poorten (winner 2007 in 2016) and Shehan Karunatilaka (winner 2008 in 2015 and 2018) have been there but faced the axe. For the past two weeks, the shortlisted writers – especially, those who fancy their options of winning – are unusually composed and modest on media. It shows a tangible human streak in these literary gods.

Some award-winning English writers – to mollify the displacement they feel in literary platforms organised by the Sinhala literati – have a dirty habit of apologising out loud by placing Sri Lanka’s English creativity as a pseudo domain. While the Gratiaen Prize continues to be a vibrant and attractive forum for writers to be a part of, publishers and literature promoters must also respond to the challenge of finding new strategies and inventive approaches to encourage more writers – the majority of who gets left behind from long and shortlists – to publish and share their work without compromising quality or creative impulse. Following the Gratiaen Trust, its work ethic, and commitment to better literature, our epoch calls for more patrons and collectives to set up platforms that parallel the Gratiaen. If indeed, the quality is guaranteed, the prize money they might offer can be negotiated.

26 Nov 2024 8 hours ago

26 Nov 2024 9 hours ago

26 Nov 2024 26 Nov 2024

26 Nov 2024 26 Nov 2024

26 Nov 2024 26 Nov 2024