18 Feb 2019 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The artists in this retrospective include Pushpakumara Koralagedara, G. R. Constantine, Jagath Weerasinghe, Anoli Perera, Janani Cooray, Bandu Manamperi, Chandragupta Thenuwara, T. Sanathanan and others.

The exhibition is important because it brings together much of the most radical and provocative artistic statements to emerge from contemporary Sri Lankan art.

The Theertha Artists’ Collective was formed by a group of such alternatively thinking artists.

While there may be a few like-minded people who work outside this artistic nanosphere, much of what may be called ‘anti-establishment’ art could be traced to this small circle.

The French Impressionists rallied against the artistic establishment, the entrenched French Salon tradition. While the National Art Gallery is the best exponent of this  country’s established art, it stands too, as clear evidence of how weak and neglected even what we may call our establishment art happens to be.

country’s established art, it stands too, as clear evidence of how weak and neglected even what we may call our establishment art happens to be.

But French Impressionistic art’s war was waged with a powerful artistic tradition, not with French politics, which was rattled by it only insofar as it approved of the Salon art so despised by the Impressionists.

Eventually, this ‘decadent’ art which shocked the establishment and the public replaced the Salon art.

As ‘The Day We Screamed’ shows clearly, the Theertha Circle has conducted its artistic guerilla war with the political establishment, not any established artistic tradition, simply because it isn’t important enough to be attacked and brought down.

Unlike in 19th century France, our political establishment doesn’t see any reason to uphold the kind of art which fills the National Art Gallery.

This is because it thinks it has nothing to gain from art. This is surely a blessing because, even though it has left our national art ‘museum’ in a pathetic state, it means that the plastic arts, at any rate, are relatively free of nefarious

political meddling.

"The Day We Screamed shows clearly, the Theertha Circle has conducted its artistic guerilla war with the political establishment, not any established artistic tradition, simply because it isn’t important enough to be attacked and brought down."

It is surely a disturbing insight into the traumatized Lankan psyche that these young artists are focusing on the physical and psychological violence which has shaped the country’s contemporary history.

Conservative minds would find many of the themes and their treatment disturbing, even shocking. But, unlike what happened long ago with the French Impressionists, there is no public or official reaction. An event which portrays the country’s scarred psyche remains marginal.

In this short article, we can’t analyse all the complex reasons behind this. But it can be safely stated that any artistic event in Sri Lanka except something officially sanctioned and promoting traditional religious and social (i.e Sinhala-Buddhist) values would be seen as marginal.

The arts have failed to assume the importance which politics and religious values (a neat and inevitable combination in our essentially feudal non-secular and non-democratic way of thinking) have taken on. In the West, politics and religion were separated long ago, with secular thinking dominant in public life, and the arts regarded as a private activity important to society’s powers of expression and mental-physical expansion.

That’s why the arts there have become very competitive and the art of those deemed as successful becomes very expensive, like real estate. We have no equivalent point of view because we as a society haven’t started thinking outside the box when it comes to the arts and much else.

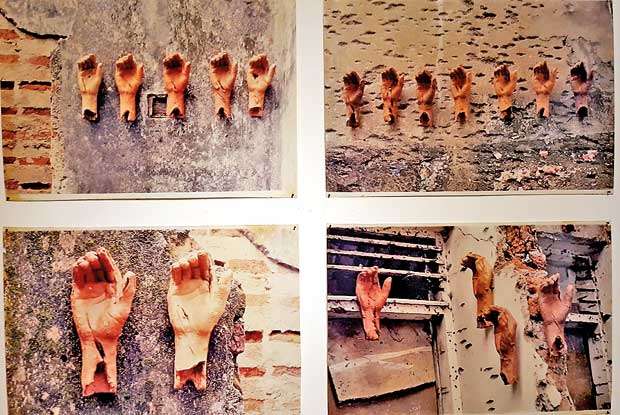

It is therefore within this existential vacuum that the Theertha group of artists express themselves. A future generation would hopefully grasp their importance more than the present one. The work of more than a dozen artists can’t be analysed here in full, but within this brief survey, we can mention Pradeep Chandrasiri’s ‘Broken Hand’ (terra cotta, wood, acrylics, nails). Kingsley Gunatilake’s ‘Year Planner’, T. Santhanan’s ‘Missing’, ‘My Friend in the Corner Stand’ by Sanath Kalubandana, the performance art pieces Bandu Manamperi, J. R. Constantine and Janani Cooray (presented as photographs), and a few more.

Chandrasiri’s damaged terra cotta hands look fragile, and expendable, hanging from ruined walls and window frames. Like many of his fellow artists in the group, he belongs to a generation scarred by the very violent 1980s decade – marked by ethnic riots, high-handed government, loss of civil liberties, the abortive JVP rebellion and a full-blown war against the state by the

Tamil Tigers.

A few of them were activists, arrested and kept in custody. Others were bystanders outraged but rendered helpless of events.

While the rest of society chose to interpret this violence in socio-political terms, these artists analysed it artistically. J. R. Constantine carried out the first ever performance art event held in this country by burning one of his own works in 1994.

Members of the group exhibited and performed at the Jaffna Municipal Library once it was re-opened to the public.

Bandu Manamperi’s ‘Barrel Man’ performance art event, in which he walked inside the library covered in bloodied bandages and carrying an empty barrel on his shoulders, signified the futility of war. In Janani Cooray’s grim ‘Pasting the Pieces,’ a sculptured body bag shaped like a charred human body was covered with pieces of coloured cloth, a symbolic glossing over of ugly truths.

"T. Santhanan expressed the horror and trauma of it in his etchings. His kneeling, headless figure cradling a head in a landscape of stark crosses is a very moving artistic statement"

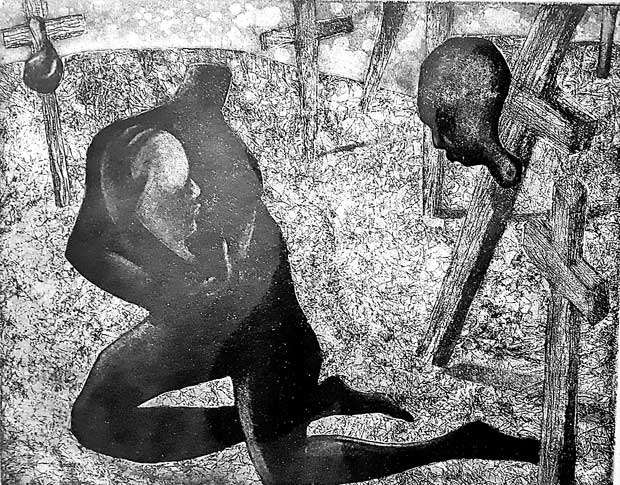

T. Santhanan expressed the horror and trauma of it in his etchings. His kneeling, headless figure cradling a head in a landscape of stark crosses is a very moving artistic statement. J. R. Constantine, in ‘The Broken Palmyrah’ and Attack on the Temple of the Tooth Relic, explored both sides of the conflict, the first as performance art and the second an acrylic painting.

‘My Friend in the Corner Stand’ by Sanath Kalubandana gives a totally new interpretation to a piece of furniture found in any household. The corner stand in the living room normally displays family portraits, flower vases and other decorative items. In this case, the artist uses it to narrate in visual terms a family history in the context of war. This corner stand displays faded photographs of a young soldier and his family. He’s holding a gun, there’s an old man who could be his father, and finally, we see his family at the almsgiving following his funeral. It’s a deeply moving artistic statement about the futility of war.

Kingsley Gunathilake’s Year Planner is made from a piece of burnt wood, said to be taken from a bombed temple. It is crisscrossed by small circles and looks like a totem pole, or a calendar kept by someone marooned on an island. The artist is rebelling against the way politicians take over time by regular political events such as rallies and elections.

Sarath Premasinghe’s ‘The Female Model of Life’ is a large oil painting. Though the technique isn’t very good, he is making an important statement – that artists, including photographs, have the privilege of working with female nudes and that amounts to a respectable form of voyeurism.

This group may seem like a lone voice in the wilderness, but it heralds a quiet revolution in the painfully slow but inevitable evolution of our plastic arts.

30 Nov 2024 50 minute ago

30 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024