09 Dec 2019 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Purple Violet of Oshantu is not a feminist novel but describes eloquently the prejudices against women cast by both men and women in close-knit communities

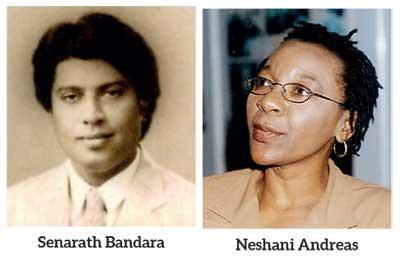

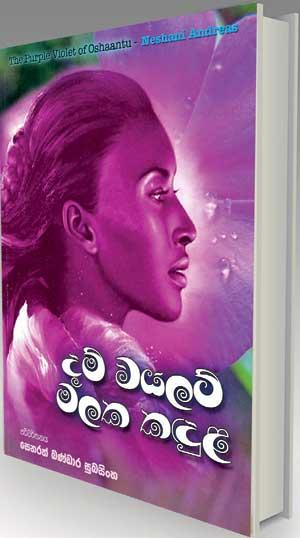

Dam Violet Malaka Kandulu is the translation of The Purple Violet of Oshantu by Neshani Andreas, a Namibian novelist. This work by Senarath Bandara Subasinghe goes a long way to  introduce contemporary African literature to Sri Lanka.

introduce contemporary African literature to Sri Lanka.

This is all the more remarkable since this is his debut translation. Our better known, full-time translators usually focus on popular titles from Europe and Latin America with better market prospects.

It’d be revealing to research and find out how many African works of literature have been translated into Sinhala over the years.

Neshani Andreas (1964-2001) started life working in a clothes factory. Her parents were fish factory workers. She subsequently attended University, became a teacher, and was appointed the Associate Director of Peace Corps in Namibia.

Her experiences while teaching at a Namibian rural school inspired this debut novel. In 2001, the author succumbed to lung cancer.

Andreas avoided the prevalent topics of social injustices caused by racism and colonialism (There is only one white man in the book, a minor character), and concentrated on the misogyny caused by traditional authority and hierarchical relationships in rural Namibia.

The Purple Violet of Oshantu is not a feminist novel. But it describes eloquently the prejudices against women cast by both men and women in close-knit communities where superstition plays a major role and nurses are thought of by some as ‘witches and bitches.’

The narrative is centred on two friends, Kauna and Mee Ali. Both are neighbours, and married to very different men–Kauna’s husband Shange is a Philanderer and a wife-beater, while  Mee Ali’s husband Michael, a migrant worker often away from home, is kind and understanding.

Mee Ali’s husband Michael, a migrant worker often away from home, is kind and understanding.

It’s Mee Ali who reveals to Kauna that Shange is not an official at the Ministry of Mining as he claimed to be, but works as a chef, which lowers his standing in Kauna’s eyes.

Kauna, compared by villagers to the purple flower, which grows abundantly in the region, has suffered both in looks and in spirit due to her husband’s violent beatings.

But she is determined to remain with him and their children instead of returning to her family.

The narrative takes another turn when Shange dies suddenly and inexplicably at home one morning. The villagers are divided in their opinions–some accuse Kauna of poisoning her husband, though there is no proof of this.

The climax of the story happens to be Shange’s funeral, and the rest of the narrative builds up slowly towards this.

It is unusual to find the story told from a woman’s perspective. Though Mee Ali is the storyteller, the grievances are not hers. They are Kauna’s, and the element of sympathy shown by Mee Ali towards her friend’s tribulations and suffering makes the story stronger.

What happens when Shange’s relatives gang up against Kauna when it comes to her late husband’s property is a testimony to the level of misogyny that can exist at village level against women, especially when they become widows.

But Kauna reacts with a surprising act of defiance which becomes a strong symbol of her independence and individuality.

It’s that which makes The Purple Violet of Oshantu a memorable reading experience.

Though some of the situations depicted are bleak, it is never oppressive. The translator has managed to preserve the essential readability of the original, his use of the colloquial language  making the book’s 206 pages a pleasure to read.

making the book’s 206 pages a pleasure to read.

Senarath Bandara Subasinghe is a former Commissioner of Income Revenue Department.

He wrote poetry in both English and Sinhala for newspapers while he was working there, and started working on translations and writing fiction after retirement. In addition to two children’s books, he has written a short story collection titled Geheniyak Novu Lankdak.

Anusaya Subasinghe who acted as a school teacher in the children’s film Ho Gana Pokuna is his daughter. She has a PhD in Drama and Theatre from the Melbourne University.

Subasinghe,Senarath Bandara, Dam Violet Malaka Kandulu, Sarasavi Publishers, Nugegoda. Pp 206. LKR 390.

28 Nov 2024 6 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 7 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 8 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 28 Nov 2024

28 Nov 2024 28 Nov 2024