26 Jan 2019 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

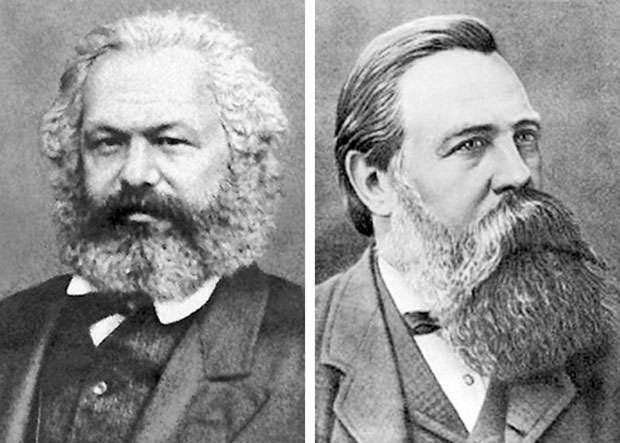

The third in a series of essays delving into the problems of our education system Both Marx and Engels realised the value of free education. They were aware of the role played by schools in the perpetuation of class hierarchies in a given society. To this end, in the Communist Manifesto, they set down as one of 10 aims the saving of education from the ruling class. It was only natural that the kind of education they had in mind was very different from the kind that existed in Europe then: they envisioned a system based on three broad layers: the mental, the bodily, and the technological. The objective of schools would be “the conversion of social reason into social force”, or the emancipation of the working class from the “crushing effects” of the capitalist system, which had made them “too ignorant to understand the true nature of... the normal conditions of human development.”

The third in a series of essays delving into the problems of our education system Both Marx and Engels realised the value of free education. They were aware of the role played by schools in the perpetuation of class hierarchies in a given society. To this end, in the Communist Manifesto, they set down as one of 10 aims the saving of education from the ruling class. It was only natural that the kind of education they had in mind was very different from the kind that existed in Europe then: they envisioned a system based on three broad layers: the mental, the bodily, and the technological. The objective of schools would be “the conversion of social reason into social force”, or the emancipation of the working class from the “crushing effects” of the capitalist system, which had made them “too ignorant to understand the true nature of... the normal conditions of human development.”

Marx and Engels, and the Soviets, were thus far ahead when it came to education reforms. Unfortunately for us, throughout colonial rule officials enacted legislation which, instead of democratising the system, solidified the class structures embedded therein

The Soviets were the first to adopt, with necessary amendments, the Marxist system. The first step was the separation of Church from State. Then in 1918, the State issued the Uniform Labour School Regulations, which brought all the schools under the so-called Commissariat for Education.

Lunacharsky, the first People’s Commissar, called for teachers to “build a new school of people” and a “new people’s school” in Russia. Four years later, in The ABC of Communism, Bukharin and Preobrazhensky pointed out why bourgeois society had not conceived a democratic system of schools, and here they identified the classist streak that had defined education, even “education for the masses”, in the Western/European/Anglo-Saxon bourgeois system, and had inspired workers with nothing more than respect for the capitalist regime.

The case of English public schools provides strong evidence for this. One of the first public schools was founded by William of Wykeham in 1382: Winchester College. It was established as a monastic institution in the aftermath of the Black Plague. Initially William had envisioned it to be “an agent of social mobility” that could give children of poor backgrounds a rigorous education he himself had not enjoyed. To this end, in the College Charter he decreed that 70 poor scholars would be educated and boarded at his school for free. The Charter lamented the poverty of the many when it stated that it proposed “to help and bestow our charity to help” needy scholars.

There were two problems though: the definition of poverty and how many of those who fitted the description of “poor and needy” were admitted. The College statutes stated that a scholar could not enter Winchester unless he came from a family earning an income of, when adjusted for inflation, around £ 4,000 a year. As David Turner in his extensive work The Old Boys: The Decline and Rise of the Public School notes, this “was more than the earnings of many clergymen” in the area, although he does admit that it “would have excluded genuinely wealthy families.”

That was just one problem. The other problem was more pronounced. From the beginning, Winchester had “attracted families far and above the ‘poor and needy’”, owing to the fact that it generated “an endless stream of curious visitors ranging from Oxford academics to the Duke of Brittany.”

Private education in the colonial era meant education in missionary schools. Not unlike the mushrooming second rate international schools of today these often imparted an inferior education preoccupied with conversion and Westernisation

Because of the need for funds, Wykeham accommodated the rich and the powerful by way of a clause which stated that “we allow... sons of noble and influential persons, special friends of the said College... to be instructed and informed in grammar with the same College.” This was to be in addition to the scheme for poor scholars, yet by 1412, “there were as many as a hundred” of the rich scholars, which meant that for most of the school’s history they “would outnumber the scholars.”

Marx and Engels, and the Soviets, were thus far ahead when it came to education reforms. Unfortunately for us, throughout colonial rule officials enacted legislation which, instead of democratising the system, solidified the class structures embedded therein. That is why there was almost always a contradiction between a stated aim of education for all and the actual practice of superior education for a few: it was as though Wykeham had come to British Ceylon.

Swarna Jayaweera pointed this out when she observed that colonial administrators were “more often conditioned by the educational practices of the metropolitan country than by the local circumstances in which their policies operated.” Education policies were thus not responsive to the needs of the country; nowhere was this more apparent than in the period from 1870 to 1920, from the time of the Morgan Committee Report to the enactment of Education Ordinance No. 1 of 1920.

Despite the fact that education in Ceylon was largely a case of grafting a system that could not be any more alien to our economy, the State was not really bothered with emulating the public school model in every respect: as Jayaweera notes, educational administration was one of the few areas “which bore little resemblance to that of its prototype.” What of private education, then?

Private education in the colonial era meant education in missionary schools. Not unlike the mushrooming second rate international schools of today these often imparted an inferior education preoccupied with conversion and Westernisation. This trend was unchecked, and by the last quarter of the 19th century there was a “rapid expansion of English education” where schools competed with each other by lowering fees, cutting back on teacher salaries, and resorting to malpractices in order to “obtain a higher grant than they were in fact entitled to” (Wanasinghe 1968). The latter point was important, because through the Morgan Report the rules of religious instruction in schools assisted by the State were revoked “so as to leave all religious bodies free to teach religion as they pleased” (ibid). It was laissez-faire all the way.

In the early period of British colonial rule there was a tussle between the authorities and missionary interests. It was only with the enactment of the Colebrooke-Cameron reforms that a real need was felt for a schools scheme which could educate a select few to staff the native civil administration. In later years, owing to the need to achieve this aim, the attitude of resentment towards missionary interests eroded to an attitude of indifference if not cooperation: the link between the State and the missionaries was apparent by 1896 when, of eight officials appointed to the Board of Education, three were clergymen representing several denominational interests and only one, and a layman at that, was explicitly representative of Buddhist interests.

The Morgan Report published its recommendations in 1869. It signaled an end of an era: from English education the State concentrated on vernacular education. But as was typical of colonial policy, this was dubiously interpreted; by the time of the coffee crash, the call of the day had turned to retrenchment. Naturally this meant the pruning of finances and the scaling down of expenditure on village schools. But there was a more insidious motive behind the policy of retrenchment, as was articulated by the then Director of Public Instruction, H. W. Green:

“It is false kindness to poor scholars in general in this country to give free or nearly free English education indiscriminately as it creates an unsettled class of aspiring youths for whom there is no employment to be found in the Colony.”

In the end, retrenchment became “the keynote of the eighties”, as Jayaweera once put it. With a limited budget and an imminent recession, the government paid no attention to the reform proposals envisioned barely a decade back, and in the end, after much debate (a cess was proposed, then hastily retracted), the State resorted to two acts of legislation which predated the Morgan Report: the Municipal Ordinance 17 of 1865 and the Local Board Ordinance 7 of 1866. With these the State had tried to revive the system of gamsabhawas that had been neglected until then, and with them it was yet again trying to implant a “prototype” from England: in this instance, the Schools Boards that had been created in the home country in 1870.

But then the revival of local government institutions to meet increasing outlays on education was, as will be seen next week, not a total success. There was one problem: missionary education and grants to missionary schools. As Jayaweera puts it, by this time “nine-tenths of government expenditure on education” was allocated for grants. Given this, it was only natural that an entrenched rent-seeking schools system would oppose any move that could undermine their dominance over education.

30 Nov 2024 29 minute ago

30 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 5 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 6 hours ago

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024