25 Oct 2024 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The train that hit and killed Thushari and the trains that we clocked at going over 75 km/h in the 20 km/h zone, were all carrying the wildlife officer

Over the years, many ideas have been put forward to solve this issue

While we have many experts who ‘know’ the locations elephants cross tracks, there is no guarantee that the elephants are aware of those locations

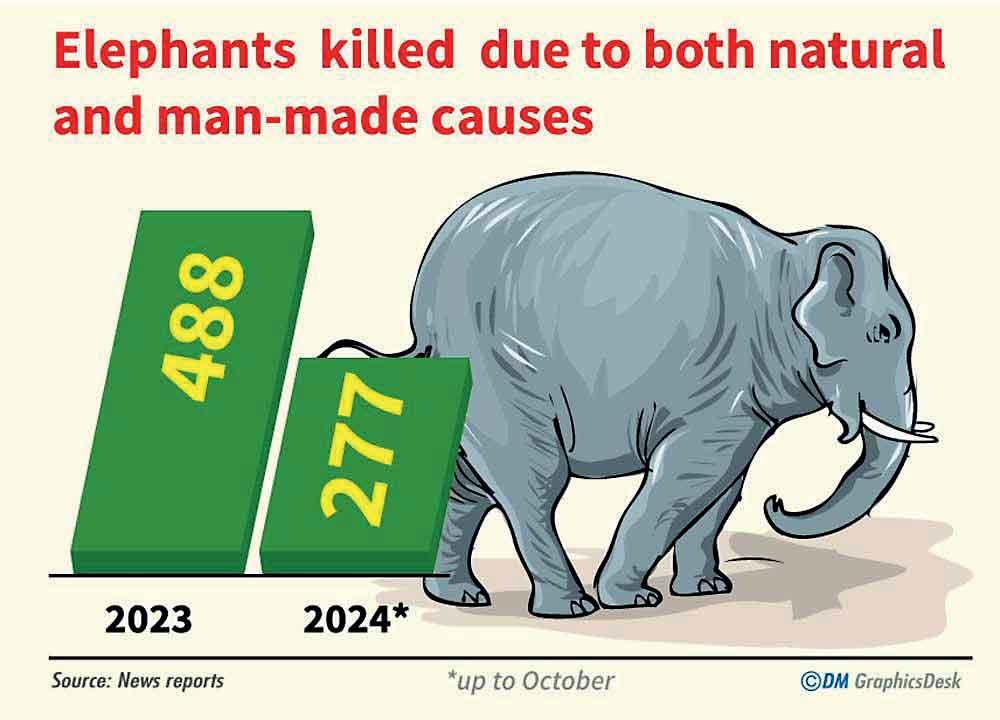

The recent deaths of six elephants killed in a train accident in one night, four in Galgamuwa and two close to Habarana on September 28th, have once again brought attention to the topic of elephants and trains. While the number of elephants killed by trains annually in Sri Lanka is around 5% of reported elephant deaths by all causes, it generates much media attention and social discourse.

The recent deaths of six elephants killed in a train accident in one night, four in Galgamuwa and two close to Habarana on September 28th, have once again brought attention to the topic of elephants and trains. While the number of elephants killed by trains annually in Sri Lanka is around 5% of reported elephant deaths by all causes, it generates much media attention and social discourse.

Consequently relevant authorities are pressurised to redouble their efforts in holding discussions and appointing committees, as they have been earnestly doing over the years.

Although train kills are a relatively small percentage of the total, the actual number of elephants killed by trains is around 15-20 per year, hence not insignificant. Also, from a conservation perspective, the impact is greater than just the number, as many of those killed are reproductively active females. Additionally, in some instances damage is caused to trains and tracks, entailing delays and monetary costs.

Over the years, many ideas have been put forward to solve this issue. While a few have been tried out in limited situations and proponents claim great success, none have been widely implemented or employed for any significant length of time, which in itself indicates something.

The actions proposed could be categorised into four main groups: those that provide warning of elephants on or close to the track, chasing elephants away when a train approaches, preventing elephants coming on to the track and enabling elephants to cross without mishap.

Low-tech solutions

The majority of proposed activities have focused on warning the train drivers of elephants being on or adjacent to the track. They include low-tech solutions such as clearing the sides of tracks of vegetation so that train drivers can spot elephants more easily or having on the ground observers relay messages to the train drivers. Suggested high-tech solutions are, fixing high-powered LED headlamps, thermal cameras or infrared cameras on trains, deploying devices that detect elephants along tracks coupled with messaging systems, and radio-collaring elephants and informing train drivers of their movements. Such solutions, particularly the techy ones are appealing, but the approach itself is fundamentally flawed. The issue is that a moving train only hits an elephant that crosses the track a few seconds in front of it.

To illustrate this point, let’s look at some back of the envelope calculations. The width of a train is about 3 m. If an elephant ambles across the track at a speed of about 4 km/h it will take about 3 seconds for it to cross 3m. If a train is travelling at a speed of 75 km/h, it equates to 21 m/second. Therefore an elephant crossing within about 3 seconds of a train arriving at the crossing point – which means an elephant crossing within 21x3 = 63 m of the approaching train – would be hit. To be conservative and to allow for slower elephants and faster trains, let’s say the ‘hitting zone’ is 100m. Now the problem is that a train travelling at 75 km/h, after applying brakes, will take almost 1 km to stop. So visualizing an elephant on the track at a distance less than 100 m is pointless because you cannot stop the train and the train will hit it. Visualizing an elephant crossing any distance beyond 100m is equally useless because the train cannot hit it. So none of the tech solutions based on visualising and early warning can prevent elephant deaths by train.

Two wild elephants died last week after being knocked down by the Batticaloa-bound fuel carriage (File Photo)

One could argue that an elephant could be standing or sleeping on the track and not moving across. So if it could be detected while the train was over 1 km away, the driver could be warned and - assuming the driver too was not napping - the train could be brought to a smooth stop and disaster averted. However, unless the elephant was intent on committing hara-kiri, this seems an unlikely happening, as surely a rail track is not the most comfortable or likely spot for an elephant to nap or stand and contemplate what would happen if he remained standing there when the train comes.

Some activities aim at providing early warning to train drivers when elephants come close to the tracks. Then the train could stop or go very slow so that it does not hit any elephants that are waiting to dash in front, reminiscent of bull running a la Pamplona. Various types of sensors such as seismic sensors, motion sensors etc. have been proposed. While the idea has some merit, it requires the deployment of a large number of such devices parallel to the tracks, involving much expenditure. Such devices not only would need to be powered to detect and transmit data and high-tech enough to differentiate between elephants and other moving things but would also need to be serviced and maintained ad infinitum while baking in the sun and drowning in rain. They would also have to be safeguarded from thieves and the elephants themselves.

While radio-collaring elephants with GPS collars can theoretically provide real time data, it would mean collaring a large number of elephants in ‘danger’ areas and replacing them every year or so, again forever. It would also require a system that continuously assesses the data and informs the drivers automatically. Given the expenses and logistics of collaring an elephant and the complexity of the data management, this approaches the realm of sci-fi. So by and large, detecting elephants and providing early warning to train drivers is also a non-starter.

Drawbacks

Activities that are supposed to chase away elephants when the train approaches are similar to above and include the fixing of high-powered horns, powerful headlights or devices along the tracks that activate flashing lights or produce loud sound as the train approaches. While theoretically feasible, how elephants will react to loud horns or very bright lights would need to be found out – the expression ‘deer caught in headlights’ comes to mind. Installing numerous devices along the tracks suffer some of the same drawbacks as of those detecting elephants and informing drivers, discussed above.

Preventing elephants coming onto the track, at first glance seems like a reasonable and easy fix. Generally such proposals are based on some type of barrier such as electric fences, railway girder fences and so on. However, one must first ask why an elephant crosses the track. Each individual elephant has a definite area it uses – which is known as a ‘home-range’ in biological parlance. Animals other than humans tend to have very elementary requirements. They do not need clothes, houses, vehicles, jobs etc. Therefore the area they use is only what is needed to fulfill their basic requirements of food, water and in some cases mates. Linear infrastructure such as railway tracks do not pay any regard to the home-ranges of elephants or other animals and they tend to lie across home-ranges. If we prevent elephants crossing railway tracks that bisect their home-ranges, they will lose access to part of their home-range. As in the case of elephants being chased into protected areas and fenced in, this would result in the affected elephants starving to death.

Therefore, by preventing elephants crossing tracks, one may save a few elephants but kill ten times more – a typical case of the cure being worse than the malady. In addition one has to consider the ‘success’ or rather the lack of it, in preventing elephants crossing barriers such as electric fences, ditches and bio fences.

The fourth type of proposal is to make it possible for elephants to cross railway tracks safely. The main ways this can be done are constructing underpasses or overpasses. In effect, having bridges for the trains so that the elephants pass under or having bridges for the elephants so that they pass over. Of the two, underpasses maybe the more practical, as it is probably easier to convince an elephant to go under a bridge rather than on one.

While underpasses could avert train-elephant collisions, they can only work if the elephants used them. So the best solution is to locate them where elephants are already crossing the tracks regularly. While we have many experts who ‘know’ the locations elephants cross tracks, there is no guarantee that the elephants are aware of those locations. Therefore, rather than relying on ‘expert opinion’ the best is to find out from the elephants themselves where they cross the tracks. This is something that can be done by radio-collaring. A few years ago, this almost came to pass when a number of development and donor funded projects agreed to provide funding for 300 elephant collars. Unfortunately the Wildlife Department declined the offer. If the 300 collars were deployed, we would by now have a very good idea of where elephants crossed tracks. While construction of underpasses for elephants is a good solution, it is a long term one and their construction for existing tracks is probably complicated and expensive. However, incorporation of underpasses is a sine qua non for any new tracks such as the proposed Dambulla-Habarana track and should have been done when the northern track was re-laid recently.

Simple remedy

However, all the fancy and tech solutions aside, there’s one obvious and simple remedy that would provide immediate results but is little talked about – going slow. Elephants almost exclusively get hit by night trains. Is it such an issue if a night train takes half an hour or one hour longer for the journey?

A newspaper article a few days ago stated the curious fact that many ‘old engines’ did not have functional speedometers, and that only experienced drivers could accurately gauge the speed of the train – ‘flying by the seat of their pants’ as it were. In this day and age when a GPS ‘head-up-display or HUD’ speedometer that can simply be slapped on the windscreen of a car, bus or yes, even a train and displays the speed in bright big numerals on the windscreen itself, can be purchased for Rs. 10,000 or less, one has to indeed wonder to what depths the Railways Department has chugged to.

Anyhow, assuming that some wealthy donors could be found to sponsor a few speedometers, if we do the same back of the envelope calculations as before, to be hit, an elephant would have to cross within 20m of a train travelling at 25 km/h and within 9m of one travelling at 10 km/h. The probability of an elephant crossing in front of an approaching train is likely to drastically decrease with closer distances to the train, hence slower speeds are very likely to prevent hits. Also, the train drivers who are keeping their eyes peeled for suicidal elephants maybe able to apply the brakes for a second or two and slow the train a tad more, so that if an elephant is hit, the consequences may be less dire.

Then the issue becomes where and for what distance the trains have to go slow. In 2018, a team of experts from the Ministry of Transport and the Wildlife Department travelled in a train and produced a report, which identified that there was possibility of trains hitting elephants along 368 km of rail tracks, with a very high danger of it along 142 km. Crawling along at 10-25km per hour over such distances is not a practical possibility. Therefore, if we are to adopt a ‘go-slow’ measure, we need to identify where elephants actually cross the tracks. Radio collaring elephants in ‘danger areas’ and determining where they are most likely to cross, could narrow down the ‘go-slow areas’ to a reasonable and practical extent. In the long-term, collar data could also be used to locate underpasses, as discussed previously.

However, no amount of identifying actual crossing points will help, unless the trains actually go slow. Just before midnight on 17th June 2011, Thushari, a young-adult elephant that was radio collared, her mother and her younger brother all got hit by a train in Galgamuwa and were killed. The length of rail track that Thushari and her family crossed regularly was about 500m and the crossing of the rail track (and the parallel Padeniya-Galgamuwa main road) by many herds along this stretch is well known. In fact, the Wildlife and Railway Departments had put up signposts along the rail track declaring a speed limit of 20 km/h through this stretch. After Thushari was killed, we checked the speed of night trains that were traversing this stretch and they were all barreling through at over 75 km/h.

This was neither the first nor the last instance that trains ‘met’ elephants along this stretch. The Wildlife Department had by this time come up with the strategy of a wildlife officer boarding the train engine at the previous station and travelling in it till the next station. The train that hit and killed Thushari and the trains that we clocked at going over 75 km/h in the 20 km/h zone, were all carrying the wildlife officer. Would it not be simpler to aim a speed gun and prosecute the offenders? Many more elephants have been killed on this stretch since Thushari’s family perished. Of the 6 elephant deaths that precipitated this discourse, the 4 that were killed at Galgamuwa – a mother and three young – were also along the same stretch.

A giant 9ft. tusker elephantroaming at night in the villages ofMorakewa, Kalpe, Ritigahawewa and Elapathwewa is causing fear and extensive damage to houses, paddy stores and agricultural crops.

Marauding tusker

Speaking to the Lankadeepa, Anuradhapura District Former MP Themiya Hurulle of Morakewa said “This marauding tusker might be one who has escaped from the killer wild elephant retention park near Kapugollewa. If not, it could be an irritated tusker that lost its home when the Yan-oya irrigation reservoir at Wahalkada was impounded.

Speaking further Hurulle said the tusker had come to his premises and caused damage to his garden and agricultural crops.

He said that the tusker charges at persons who direct torchlight at it. He said that the tusker cannot be chased away by lighting ‘thunder-crackers’ (ali -wedi).

He said that he has made a request to the Anuradhapura District Secretary and Wild Life Conservation authorities at Anuradhapura and Horowpothana to have the elephant captured and taken back to the wild Elephant retention park.

23 Dec 2024 7 hours ago

23 Dec 2024 9 hours ago

23 Dec 2024 23 Dec 2024

23 Dec 2024 23 Dec 2024