01 Feb 2019 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The fourth in a series of essays delving into the problems of our education system

While the British were able to deploy local authorities to meet the increasing costs it had to incur on education, they had to resolve two distinct yet related issues, namely the dominance of the missionary societies and the inadequacies of existing legislation to help them achieve their aim of rationalising the sector.

By the 1880s, “nine-tenths of government expenditure” was allocated to the grants-in-aid system introduced through the Morgan Report. The system catered to schools that fell outside the State sector, but it heavily favoured Christian institutions: at the turn of the 19th century there were 181 assisted schools managed by Buddhists, Hindus, and Muslims, as opposed to 1,082 managed by Christian denominational bodies.

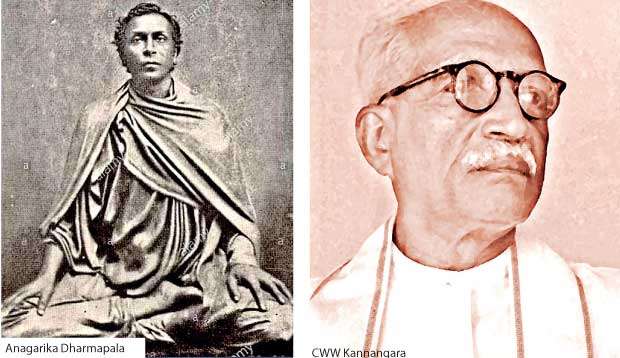

Until the enactment of Education Ordinance No. 1 of 1920, colonial education policy was essentially a tussle between an official policy of retrenchment and devolution on the one hand and a covert policy favouring denominational interests on the other. It was taken for granted that education was for the few, and not the many. Documents from this era show clearly that a distinction was drawn between a classical liberal arts education (for the elite) and a technical industrial education (for the poor). It was this which, in part at least, compelled Angarika Dharmapala to denounce the absence of proper industrial/technical schools in the country, something that bewildered the colonial authorities themselves; as W. D. Sendall, the then Director of Public Instruction, noted in 1863 in his report on education.

There can be no doubt that Industrial Schools, whatever they are or have been, might be made of the greatest possible use in Ceylon. The recent breakdown of the Colombo Industrial School, the only considerable Institution of the kind that has been established, is a phenomenon, the causes of which are at present a mystery to me, upon which I can offer no opinion.

The cause, however, was not really a mystery. It was essentially the separation of a curriculum based on the Classics – at its inception the Colombo Academy taught the following: Logic, Elements of English Law (Blackstone’s Commentaries), Principles of Natural Philosophy, Astronomy, Sinhalese, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew – from a curriculum based on a smattering of English, the vernaculars, and Evangelism – which was imparted to village schools. It was a carefully sustained distinction that kept the rural child from the town child, and it sped up a process of urbanisation.

There has been a great demand for education, and this demand has been principally met in the town – the wealthy villager who wants his son educated usually sends him to one of the big schools in the nearest town. One result has been that the rising generation has been brought into touch with town life, and that the wants of a town population have been created amongst the rural population... The basis of all changes of manners and customs is imitativeness – create a fashion and change a people. (Denham 1912: 158).

This distinction continued well into the 20th century. When in 1915 (a tumultuous year in our history if ever there was one) a scheme was prepared by the government to award 30 free scholarships through Royal College to students, it was ascertained that the scholarship holding outsiders or “bounders” had “started with a slight handicap in secondary school subjects”, like Latin. They were, however, more adept at the more “technical” subjects, like mathematics.

Regi Siriwardena in Among My Souvenirs depicts the class structures that coloured the perceptions about these bounders, perceptions which a comment to a Facebook post the other day (quoted by Malinda Seneviratne weeks ago) exemplified:

That’s what I say - whether you live in the village or town -THE BREED SHOWS. Most of the baiayas who have been attacking you - their ancestors may perhaps have been from the class your parents would have employed as servants. Thanks to free education & the “shishtathvaya” - as well as the district wise selection for universities - some may be in comfortable jobs, donned in western attire - but their breed is from the gutter. (Quoted verbatim)

Moving on. The experiment with Local Government institutions to reform the education system was, to put it mildly, an utter failure. It did not help the government to cut back on the costs of maintaining that system, since from 1890 to 1900 those costs rose from Rs. 474,387 to Rs. 869,837 (i.e. more than 83%). On the other hand, attachment to the “old school tie” ensured that reforms, if they could be called reforms at all, were tilted in favour of missionaries; as Wanasinghe (1968) points out, “most of those who held positions of responsibility in the Local Bodies received their education in the denominational schools.” With the enactment of the Town Schools Ordinance of 1906 and the Rural Schools Ordinance of 1907, the monopoly of the missionaries was more or less cut down, though not completely.

Moving on. The experiment with Local Government institutions to reform the education system was, to put it mildly, an utter failure. It did not help the government to cut back on the costs of maintaining that system, since from 1890 to 1900 those costs rose from Rs. 474,387 to Rs. 869,837 (i.e. more than 83%). On the other hand, attachment to the “old school tie” ensured that reforms, if they could be called reforms at all, were tilted in favour of missionaries; as Wanasinghe (1968) points out, “most of those who held positions of responsibility in the Local Bodies received their education in the denominational schools.” With the enactment of the Town Schools Ordinance of 1906 and the Rural Schools Ordinance of 1907, the monopoly of the missionaries was more or less cut down, though not completely.

From the two Schools Ordinances (which were, not surprisingly, failures), we come to two landmark acts of legislation, the Ordinance of 1920 and the Ordinance of 1939. The former made education the responsibility of the State, with financial centralisation seen as more desirable “in the interest of a more equitable distribution of available resources.” There was, of course, opposition to this policy reversal, especially owing to the decline in export earnings after 1922. In fact, another Commission appointed in 1923/1924 recommended that while education was a “national service” it should not be paid for from the “general revenue” of the country. The recommendation was, not surprisingly, shot down by the then Governor Hugh Clifford.

Between 1920 and 1939, there were sweeping changes throughout the country, and not just in the realm of education. The Donoughmore Constitution had nativised the central administration of the country through the granting of the franchise and the appointment of Committees, the Chairmen of which were Ministers. But even these were subject to a caveat: the Governor reserved to himself powers which overrode decisions of the Ministers. It was this that led the first Education Minister, C. W. W. Kannangara, to galvanise opposition to the Committee system. This led to the 1939 Ordinance and later the Special Committee on Education.

What needs to be pointed out is that these reforms were progressive but failed to address a problem. Our education system was based on a structure of schools which differentiated between a classical education and a technical/industrial education. The latter was seen, then as now, as projecting a rural bias while the former was seen as projecting an urban bias. In other words, as N. M. Perera noted in The Case for Free Education (which lambasted the Report of the Special Committee), if such distinctions were sustained the proposals of the Report, no matter how reformist, would result in a different education for village children and for town children.

Here, then, is the real problem that free education ought to have combated, but did not: the doing away with the distinction between formal and practical education. By separating the practical from the formal, colonialism entrenched a system whereby, as Perera beautifully put it, “the sons of the rich have all the opportunities and the sons of the poor all the disabilities.” No matter how progressive educational reform proposals, including the Special Committee Report, may be, by missing out this fact they are all doomed to flounder. The Kannangara reforms thus did not achieve what they set out to achieve, because they were content in viewing reforms through the continuation of colonial policies; they were content in grafting those reforms on a structure that was, from its inception, opposed to equality and equity.

But of course, equality being the call of the day, schools and universities managed to usher in the “bounders” who had been debarred from the privileged institutions in the British era. My contention is that this was not enough; the Special Committee Report, which represented a mishmash of views that never tallied with each other, was in that sense a scuttled attempt at reform. In two spheres especially there was a failure: the teaching of English, and the Grade Five scholarship.

I will explore these next week, because on them rests the problem which these articles seek to sketch out: the reason as to why international schools, denounced so bitterly by the former Minister of Education, emerged in the 1980s.

30 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 5 hours ago

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024