18 Aug 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Traffic congestion and air pollution go hand in hand

It’s a crystal clear fact now. Colombo’s air quality index improved by leaps and bounds during the COVID lockdown phase. But this jubilance is short-lived as it’s predicted that the pollutants will again encroach the city when traffic returns to normal. Both public and private institutions including schools invite more than 1.9 million people and over 500,000 vehicles to this city daily. Colombo wetlands, probably the only green filter that attempts to buffer air pollutants, is rapidly being destroyed for cosmic projects like road construction. And it’s hilarious to expect “Colombian” inhabitants to live a long life with this much of environmental damage. During the hype generated during the General Elections it was hard to find a candidate who had a proper agenda to combat environmental pollution.

It’s a crystal clear fact now. Colombo’s air quality index improved by leaps and bounds during the COVID lockdown phase. But this jubilance is short-lived as it’s predicted that the pollutants will again encroach the city when traffic returns to normal. Both public and private institutions including schools invite more than 1.9 million people and over 500,000 vehicles to this city daily. Colombo wetlands, probably the only green filter that attempts to buffer air pollutants, is rapidly being destroyed for cosmic projects like road construction. And it’s hilarious to expect “Colombian” inhabitants to live a long life with this much of environmental damage. During the hype generated during the General Elections it was hard to find a candidate who had a proper agenda to combat environmental pollution.

Air is the most essential health commodity that humans yearn for, even more than food and water. It’s the least appreciated, but the most critical life support substance for us humans. Air quality might be the only commodity that we cannot select or bargain for. Clean water and organic food can be purchased for exorbitant amounts of money. But as breathing beings, we are compelled to inhale whatever is out there in the environment. And no commercially available air conditioner can filter odourless killer gases like carbon monoxide; there are no technical solutions.

Have you ever had eye, nose, throat, lung irritation, coughing, sneezing, runny nose, and shortness of breath when walking on the busy streets of Colombo?

Risk of dying young

In one of the largest studies done involving 8 million people from seven countries published in the famous medical journal “Lancet” revealed the much-awaited bitter truth concerning city dwellers. According to this research, people who lived within a city away from parks and greenery had short lifespans. They died young due to medical conditions such as heart disease, lung disease, strokes, and cancer. The opposite was true as well. For every 2% increase in greenness within 500 metres of their home, there was a 4% lower chance of early death. Blood tests and urine samples in research subjects showed that vegetation boosted blood vessels and heart health by reducing stress and improving air quality. We already knew that urban greenery projects like new parks and preserving wetlands promoted public health activities like exercise and recreation. But this groundbreaking research proved some precious insights to mitigating climate change in a city using greenery.

Heart and lung damage

You might recall the term PM2.5 used in describing air quality and wondered what it meant. PM2.5 stands for particulate matter or tiny particles in the air that are two and one half microns or less in width. These droplets are so small that they traverse down to the deep passages of your lungs and cause serious health effects. In a research, it was found that PM10 levels in Colombo range from 72 to 82 μg/m3. Sadly the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that the average city PM10 level be less than 20 μg/m3. Have you ever had eye, nose, throat, lung irritation, coughing, sneezing, runny nose, and shortness of breath when walking on the busy streets of Colombo? This “allergy” should be the particulate matter causing bodily damage within you. The long-term adverse effects are more sinister than the instant ones. Research has proven that daily particulate matter exposure will increase respiratory and heart disease, hospital admissions, emergency department visits, and deaths due to cancer. So where does this particulate matter come from? The outdoor sources are from standard vehicle/construction equipment exhausts and other operations that involve the burning of fuels. The indoor sources are the fuel that we use for cooking and tobacco smoking.

Banning entrance to Colombo city

Hypothetically where the policymakers crave for more bridges, vehicles, and workforce into the city, the controversial solution to prevent air pollution related deaths is to ban the elderly, patients with heart/lung disease, and the children from entering the Colombo city limits. Hospitals and schools should ideally be shifted to venues outside the city. Schoolchildren should not be allowed to spend most of their early life studying in a city that has polluted air. Sadly in real life, the opposite happens; not just within Colombo, but in the historical city of Kandy.

The incidence of respiratory/ lung symptoms among school children attending a school in Colombo situated close to a busy main road was significantly higher than that of children attending a school situated in a rural area, in a research done by Nandasena et al. in 2007. Air pollutant (sulphur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide & Total Suspended Particle) levels were significantly higher in the premises of the Colombo school as compared to the rural school in the same study. Another study conducted by Senanayake et al. in 1998 examined the air pollutant levels measured at the Colombo Fort air monitoring station and rates of hospital attendance for wheezing needing emergency treatment at the Lady Ridgeway Hospital for Children. Out of 30,932 children who required nebulizer therapy in the emergency treatment unit at Lady Ridgeway for one year, the highest number of episodes of nebulization occurred on the most polluted day (concerning toxic gases sulphur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide ) and the lowest number of nebulizations occurred on the least polluted day in a given week.

Wetlands – probably our only saviour

A journey in search of a messiah to curb air pollution will lead us to the Colombo wetlands. I have written an article about the benefits of Colombo wetlands in the Daily Mirror some time back. The marshes within the Colombo city is rapidly shrinking. What remains is a tiny patch of 19 square kilometres. To add insult to injury the Nawala wetlands is facing an untimely death by a proposed lengthy overhead bridge linking Kotte to Nawala School Avenue. It’s not just the construction of bridges that destroy wetlands. The long-term exposure of flora and fauna of a marsh, to vehicle emissions, and noise does severe irreversible damage. It is postulated that King Parakramabahu the 6th selected Kotte as his kingdom not merely citing security concerns, but because of the health benefits he foresaw from the wetlands.

Prof. Amal Kumarage of the Transportation Science Division at the University of Moratuwa, has stated that the loss incurred daily as a result of traffic congestion in Colombo is over Rs.500 million. Traffic congestion and air pollution go hand in hand. If these scientific facts are analysed by officials of the road development authority intelligently, building further bridges that invite more vehicles to the city should be disallowed immediately.

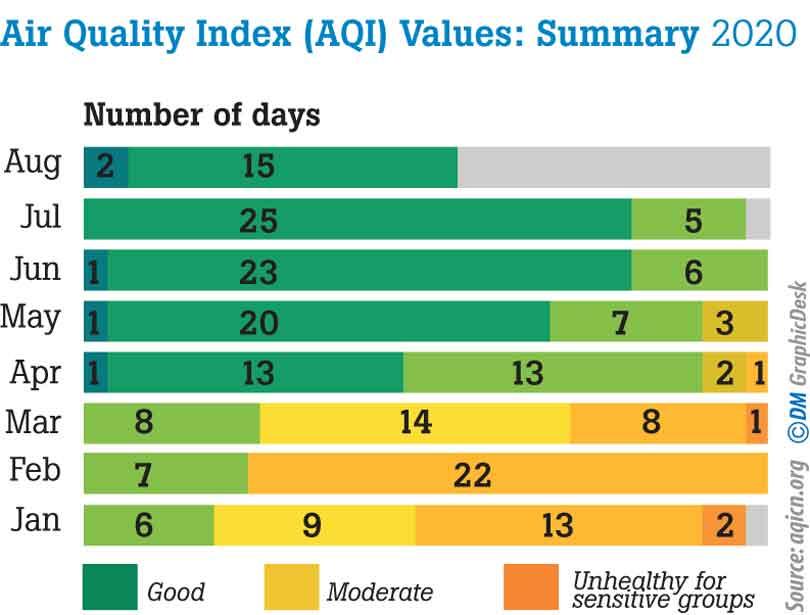

Lockdown miracle

The Air Quality Index measured at the Colombo US embassy reveals some fascinating details on what COVID-19 lockdown did to the environment. In March, before lockdown the particulate matter (PM2.5) levels in Colombo city air was dangerously high around 100-125μg/m3 for 8 consecutive days and exceeded the fatal level of 125μg/m3 for one day. In May during lockdown for 20 days these levels came down to the range of 25-50μg/m3 which indicated healthy and breathable air in the city. These are solid facts that should lead to intelligent debates. Witnessing a massive harvest of certain types of fruit like Rambutan and Durian makes me wonder whether trees are rejoicing over the unpolluted fresh air during curfew days.

If the authorities are keen on the air quality and wellbeing of the city dwellers, immediate steps should be taken to prevent further destruction of Colombo wetlands. It would be unsightly to witness oxygen bars in this city once the air pollution exceeds a certain threshold. The wetlands could be the last line of defence preventing the “Colombians” from an untimely, slow and painful death.

(The writer is a Consultant in Rheumatology and Rehabilitation)

27 Nov 2024 7 hours ago

27 Nov 2024 8 hours ago

27 Nov 2024 8 hours ago

27 Nov 2024 9 hours ago

27 Nov 2024 9 hours ago