04 Jan 2021 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Greek tragedian Sophocles’ Antigone is centred on a burial: whether the remains of a dead prince – as dictated  by custom and culture – should be given burial, or whether it should be left rotting on the roadside as the country’s government has ordered. First produced around 441 BC, the main contention of Sophocles’ play is the friction between the law of the State – man-made, arbitrary, governed by the hot-headedness of politics – and that of “the gods”: values, customs, rituals, and common sense that have come together to make a people’s traditional heritage.

by custom and culture – should be given burial, or whether it should be left rotting on the roadside as the country’s government has ordered. First produced around 441 BC, the main contention of Sophocles’ play is the friction between the law of the State – man-made, arbitrary, governed by the hot-headedness of politics – and that of “the gods”: values, customs, rituals, and common sense that have come together to make a people’s traditional heritage.

The main argument of Antigone comes to haunt our intelligence as the unnecessary and arrogant debate over the

|

Sophocles |

funeral rites of Sri Lankan Muslims said to have died of Covid-19 continues unresolved.

Walking over the global practice – and revoking its original position – in March 2020, the Sri Lankan state-enforced “cremation only” as the standard to dispose of bodies of the country’s Covid-infected deaths. With a high proportion of them responding to the Sinhalese-Buddhist label, a diverse body of politicians, heretics, influencers, and experts insinuated or declared that grave health threats may arise from burials.

Burial of the Covid-infected dead, some of them suggested, could contaminate the underground water reserves. Leading experts of the field downplayed such claims as improbable. While the issue was debated in Parliament by Muslim members of across the floor, a defiant Sinhalese-Buddhist membership in the house, in media, as well as in science and technology continues to advocate “cremation only”.

"A taboo to the Muslim, cremation, to the Sinhalese-Buddhist, is a customary and symbolical letting go of the dead. For a person who has lived long enough around the Indian Ocean and is privy to how occasional bursts of wildlife- or water catchment-patriotism works, the racial implications of the “cremation only” hysteria is not too difficult a conceptualization"

As a distinct ethno-religious community with a deep connection with its customs, rituals and practices – from day-to-day events such as prayers, food preferences and dress sense, to allowances and prohibitions that govern over gatherings, weddings and funerals – the Muslim community’s distress at being compelled to accept cremation over burial was obvious from first. The masses of the Muslim community are not reconciled with the idea of cremating their dead. For the majority of Sinhalese-Buddhists in the country, cremation coincides with “their way” of disposing of dead persons.

A taboo to the Muslim, cremation, to the Sinhalese-Buddhist, is a customary and symbolical letting go of the dead. For a person who has lived long enough around the Indian Ocean and is privy to how occasional bursts of wildlife- or water catchment-patriotism works, the racial implications of the “cremation only” hysteria is not too difficult a conceptualization.

A taboo to the Muslim, cremation, to the Sinhalese-Buddhist, is a customary and symbolical letting go of the dead. For a person who has lived long enough around the Indian Ocean and is privy to how occasional bursts of wildlife- or water catchment-patriotism works, the racial implications of the “cremation only” hysteria is not too difficult a conceptualization.

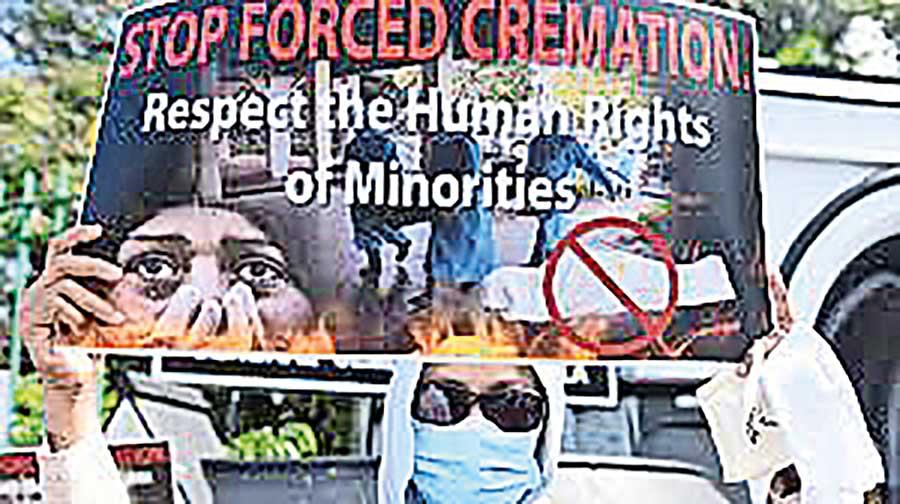

What festered as frustration within concerned circles – the Muslim community at its heart – began to crack and spill in vocal protests over insensitive and dubious conduct in disposing of Muslim bodies started to circulate in the news. One of the most shocking incidents to be reported laid bare the ruthlessness of authorities when a three-week-old child of Muslim parentage, having died from Covid 19, was cremated without the parents being given a chance to grieve. Media reported instances where, against the wishes of families, court orders had been obtained by police to carry out cremations. On 15 December 2020, Associated Press was cited by several international media sources claiming that the Sri Lankan government had reached out to the Maldives – the underground water levels of that country notwithstanding – for Sri Lankan Muslim bodies to be buried there. As social activist Shreen Abdul Saroor conceded in a new media share on 23 December, the Sri Lankan government rode to power by releasing from a bottle the genie of anti-Muslim hatred. It was now struggling to restore the miscreant in its place.

In the context of things, there are reasonable grounds for one to think that Sri Lanka’s Muslim community is being culturally bullied and that its resilience is being unnecessarily tested. The perverse sadistic pleasure of hurting one’s sensibility by inflicting on that person what he/she considers to be a taboo or a sin must not be applied to a multi-faith, multi-cultural community as it does not make good governance. However, modern-day Sri Lanka has a rich history of insidiously hurting the sentiments of ethno-religious and cultural minorities: despite the country’s high literacy (sic), a history from which it resists instruction. From declarations of “Sinhala only” in language policy to similar declarations about the bloodlines that made the government feelings and emotions of smaller groups have periodically either been pinched or punched.

"Burial of the Covid-infected dead, some of them suggested, could contaminate the underground water reserves. Leading experts of the field downplayed such claims as improbable. While the issue was debated in parliament by Muslim members of across the floor, a defiant Sinhalese-Buddhist membership in the house, in media, as well as in science and technology continues to advocate “cremation only”

In Sophocles’ play Antigone – the dead prince’ sister – was the king’s favourite niece. Defying the man-made state

|

A scene from Antigone as a painting |

decree, she took it on herself to uphold the divine law of burial by performing symbolic rites on the deceased. While a host of Muslim politicians plead with President Rajapaksa to hear the cause of their community, a powerful minister within the government, too, vocally expresses his mind against cremation-only. With a local government election being anticipated, Sri Lanka keeps watching over this developing plotline.

Sophocles’ Antigone ends in tragedy.

When the government granted the dead prince Polyneices a burial it was already too late. As the prophet, Teiresias warned the headstrong king that the gods were angered by the contravention of their divine law of burial.

Though he withdraws the gazette, Creon is too late in preventing tragedy. Antigone, earlier arrested for breaking the state order, takes her life. Shocked by the death, the king’s son Haemon (also Antigone’s admirer) kills himself. This leads the queen Jocasta to take her life as well.

In Sri Lanka, we don’t have to get all that Greek or pagan. But by respecting the Muslim sensibility and the State-issue Science text book we can dispel hysterics of viruses that live on dead bodies which, in turn, contaminate underground water. Less dramatic, it is yet infinitely a less cumbersome course than to pick the pieces of a society cracking in flames.

30 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024