05 Jan 2022 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The biggest issue Sri Lanka faces is a systemic lack of respect for the rights of its citizens, particularly – but not exclusively – its minority citizens. This is rooted in a culture of impunity that is in turn rooted in a failure to hold to account those, on both sides, who committed some of the worst atrocities this century”

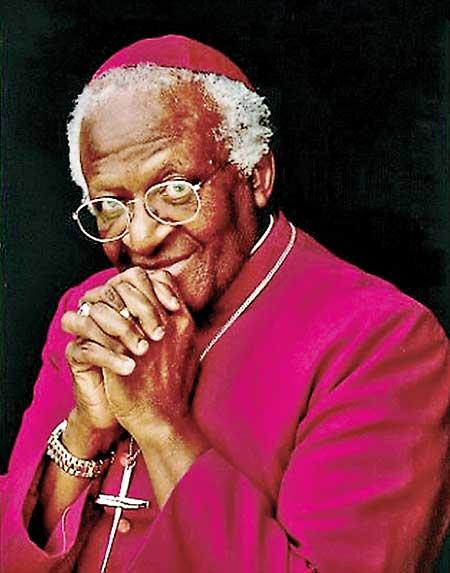

- Desmond Tutu

Desmond Tutu is not just one man. He is a larger than life representative of an Era. Not just a by-standing, passive representative of that Era, but a defiant, militant, protesting representative of a movement that sought to bring equality, human dignity, economic justice, reconciliation etc. to land that was afflicted with the curse of racial discrimination. He was, after Nelson Mandela, perhaps the most well-known anti-Apartheid activist, although his life’s calling was Priesthood. Unlike many in the priest’s robe, Archbishop Desmond Tutu believed that there could not be a heaven when there was injustice, suppression and indignity on earth.

representative of that Era, but a defiant, militant, protesting representative of a movement that sought to bring equality, human dignity, economic justice, reconciliation etc. to land that was afflicted with the curse of racial discrimination. He was, after Nelson Mandela, perhaps the most well-known anti-Apartheid activist, although his life’s calling was Priesthood. Unlike many in the priest’s robe, Archbishop Desmond Tutu believed that there could not be a heaven when there was injustice, suppression and indignity on earth.

The first time, that I got interested in this charismatic Christian Bishop was when the Song ‘’ Gimme hope, Joanna’’ by Eddie Grant became popular internationally in the eighties, Sri Lanka included. ‘ Even the preacher who works for Jesus, the Archbishop who’s a peaceful man…………’ went the lines of that iconic song. At first as a twelve-year-old, I had thought that this was a love song to a girl by the name of Joanna, until a little later, I came to learn that it was all about Apartheid which was then, the wicked governing system in South Africa.

Champion of the weak

Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s credentials as a Champion of human rights and equality are well documented internationally. Yet for Sri Lankans, in particular, Tutu could have been a beacon of light in their endeavour for peace and reconciliation after the end of the brutal 30-year civil war. As the Chairperson of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa, he had experience of treading the fine line of vindicating the rights of and reparation of victims of apartheid discrimination while not polarizing the white and black communities who have been seeing each other as enemies for decades. But unfortunately, Sri Lanka never bothered to learn from people like Desmond Tutu and the South African experience in general. Yet Desmond Tutu was concerned and interested in the post-civil war rebuilding in Sri Lanka and intervened several times to ensure that reconciliation, accountability and reparation was carried out without delay. Very few Sri Lankans are aware of the involvement of Desmond Tutu in ensuring the accountability undertakings given by Sri Lanka were honoured and implemented. Not only was his concern for equality and human dignity and rights confined to South Africa, but he strove for international solidarity in issues that involved grave human rights violations and suppression of human dignity. As much as he urged for boycotts and international pressure to end apartheid in South Africa, he later supported campaigns for rights, dignity and equality in other hotspots such as Palestine and Sri Lanka. His candid and powerful, yet empathetic words and universally acknowledged appeal could have been used by Sri Lanka to shape a better world opinion towards Sri Lanka, if the Sri Lankan governments were genuinely interested in ushering in lasting peace for the once war torn land. But they did not and people like Desmond Tutu were seen as enemies who lobbied on behalf of the Eelamists.

Putting pressure on Sri Lanka

When the Sri Lankan government sought membership of the UN Human Rights Council in the year 2008, it was Desmond Tutu who urged the international community to prevent that on the basis that Sri Lanka was far short of the high standards of human rights which were to be maintained and that there were systemic abuses by state armed forces such as disappearances, extrajudicial killings and torture. Needless to say Sri Lanka’s bid failed. Again it was in 2012, that Tutu and Mary Robinson urged the UN Human Rights Council to demand accountability from Sri Lanka for the alleged violations of international law, to introduce mechanisms to ensure that the government stayed true to its commitment for accountability and failing which, to support the establishment of an independent investigation. It was instrumental in the Council passing an important resolution supporting monitoring and reporting on Sri Lanka by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

For Reconciliation and lasting peace

His interest in Sri Lanka did not end there. It was in the year 2014, that Tutu and 38 others, urged for the establishment of an independent international Commission of Inquiry with a view to guiding an errant Sri Lankan government which was making a mess of the entire reconciliation and peace building effort, towards the path to justice and reconciliation. Consequentially, a resolution that established an independent international investigation by the UN. was adopted and the much hyped opposition from the Sri Lankan government to the two resolutions in 2012 and 2014 received little support from the international community. Obviously, Tutu was seen as an enemy of Sri Lanka and all his efforts as intervention in a country’s affair. Where Sri Lanka ended up in terms of Reconciliation and lasting peace as well as its international repute, testifies to Desmond Tutus farsightedness.

His interest in Sri Lanka did not end there. It was in the year 2014, that Tutu and 38 others, urged for the establishment of an independent international Commission of Inquiry with a view to guiding an errant Sri Lankan government which was making a mess of the entire reconciliation and peace building effort, towards the path to justice and reconciliation. Consequentially, a resolution that established an independent international investigation by the UN. was adopted and the much hyped opposition from the Sri Lankan government to the two resolutions in 2012 and 2014 received little support from the international community. Obviously, Tutu was seen as an enemy of Sri Lanka and all his efforts as intervention in a country’s affair. Where Sri Lanka ended up in terms of Reconciliation and lasting peace as well as its international repute, testifies to Desmond Tutus farsightedness.

Yet again, in 2013, when the Mahinda Rajapaksa regime was in power and the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) was to be held in Sri Lanka, Tutu urged for a boycott on the basis that the government had acted without integrity, urging that the world had to pressurize Sri Lanka by such a boycott of the CHOGM. Although the meeting was held, it became the CHOGM with the lowest ever attendance of governments with only 27 of the 53 participating.

The Archbishop who’s a peaceful man

Tutu has been campaigning for the safeguarding of minority rights in Sri Lanka, right from the conclusion of the civil war. On May 18, 2010, Tutu, together with Lakdhar Brahimi, penned “If Sri Lanka is to build a more inclusive and democratic state for all its ethnic communities, there is an urgent need for far-sighted political leadership, able to reach out to all communities and serve all its citizens. This has, so far, been lacking”. In his view, human rights and the rule of law had to be a main pillar in Sri Lanka’s future of nation building, which meant, inter alia, repealing the draconian state of emergency and re-establishing the Constitutional Council which had been effectively dismantled by Mahinda Rajapaksa. Seeing that the domestic court system was neither equipped nor brave enough to look in to allegations of grave abuses and crimes during and after the civil war, he encouraged the Sri Lankan government to opt for an independent international mechanism as a step forward. In 2012, Tutu, together with Mary Robinson, portended that unless Sri Lanka did effectively address the issue of past crimes, it would continue to haunt Sri Lanka’s people and could ignite violence once again. Again and unsurprisingly, it all fell on deaf years of the adamant Sri Lankan government. He was ready with his open arms to be our friend, but his message was too bitter for the authorities.

He was the ‘ …Archbishop who’s a peaceful man’ as Eddie Grant sings, but who roared like a lion in face of injustice and discrimination. He could have been our friend!

28 Nov 2024 58 minute ago

28 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 5 hours ago