19 Oct 2024 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The last bastion of independent Buddhism, became a haven for the Muslims in their hour of distress

Being traders, Muslims also had access to the Ports, links with the outside and therefore were knowledgeable on matters of the world

Sri Lanka’s history of peaceful relations that had existed between the Sinhalese and the Muslims, stands as a contrast against the mass destruction taking place in the Middle East in the name of ethnicity and religion.

Sri Lanka’s history of peaceful relations that had existed between the Sinhalese and the Muslims, stands as a contrast against the mass destruction taking place in the Middle East in the name of ethnicity and religion.

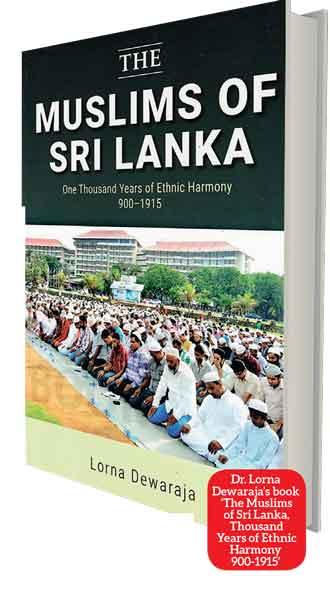

The late, eminent historian Dr. Lorna Dewaraja, whose insights of the close bonds that had existed between the two ethnic groups in Sri Lanka puts to shame the ongoing fighting states in her book ‘The Muslims of Sri Lanka, Thousand Years of Ethnic Harmony 900-1915’ that “except for a riot that took place in 1915, caused by political and economic tension rather than a confrontation between Islam and Buddhism,” the harmonious relationship that developed between the indigenous inhabitants and the Muslims, continued uninterrupted and they lived together peacefully for over a thousand years.

A Vijitha Yapa Publication, last printed in 2021, the author, encouraged by Sri Lanka’s first Foreign Minister, A.C.S. Hameed, had dug deep into the roots of Muslims and makes the disclosure that the Muslim community never showed political ambitions of making conquests in Sri Lanka. This was “unlike in India, where Islam made its entry as a conquering, proselytizing force.”

A Vijitha Yapa Publication, last printed in 2021, the author, encouraged by Sri Lanka’s first Foreign Minister, A.C.S. Hameed, had dug deep into the roots of Muslims and makes the disclosure that the Muslim community never showed political ambitions of making conquests in Sri Lanka. This was “unlike in India, where Islam made its entry as a conquering, proselytizing force.”

Circumstances did draw them into the political whirlpool and the author speaking of the roles played by the Muslims in the island’s political history, discusses the magnanimity of Sri Lankan Kings who gave them the freedom to pursue their faith and trade which enabled them to be absorbed into Lankan society.

The Muslims, enjoyed a monopoly in the jewellery, pearls, gems and spice trade until the unexpected arrival of the Portuguese in the island in 1505 that dealt a death blow to the peaceful exchange of commodities with the Sinhalese. This however, led them ultimately to participate in Lankan politics.

Muslims and King of Kotte

“Even at the time of Portuguese landing,” she states “a number of Muslim ships had been anchored in the Colombo harbour. Sensing trouble on finding that the Portuguese were erecting a fort, the Muslims had warned the King of Kotte – Parakramabahu 1X (CE 1489-1513) of the potential threat.”

The King’s attempts however, to oust the intruders with the help of the Muslims and the Malabars, had met with little success.

The Sinhalese, had always been essentially farmers. With caste prejudices, they were preoccupied with the cultivation of paddy lands while the Muslims as traders, did not come in the way of their occupation.

Problems commenced when the Portuguese who arrived in the island, discovered that the snag in achieving a monopoly of the profitable cinnamon trade was the presence of Muslims. This led to cause the rift between the Muslims and the Europeans.

The “Vijayaba Kollaya” of 1521 – a turning point in Lankan history, directly impacted on the trek of the Muslims from the coastal belt to the interior of the island. The Portuguese, who befriended Bhuvanekabahu V11 (CE1521-1551,) the new King of Kotte, persuaded him to expel the Moors from Colombo. Bhuvanekabahu, being afraid of his ambitious brother – Mayadunna (CE1521-1581,) the new King of Sitavaka and badly in need of assistance of the Portuguese, complied. The Moors as a result, taking refuge in the Sitavaka Kingdom, rallied round Mayadunne, now confirmed as a nationalist leader. And to fight the Portuguese, they brought the forces of the Zamorin of Calicut which intensified the Portugese hatred of the Moors. And the bitter rivalry between the Christian power and the Muslims that prevailed in Europe, was vigorously pursued on the island.

Although Mayaduue and his son Rajasinghe 1 (CE1581-1592) carried on relentless warfare with the Portuguese, the political developments that followed sent Muslims further into the  interior. Bhuvanekabahu’s successor Dharmapala (CE1551-1597) bequeathed Kotte Kingdom to the King of Portugal. And with the death of Rajasinghe 1, the son of Mayadunne, Sitawaka was annexed to the Portuguese territory.

interior. Bhuvanekabahu’s successor Dharmapala (CE1551-1597) bequeathed Kotte Kingdom to the King of Portugal. And with the death of Rajasinghe 1, the son of Mayadunne, Sitawaka was annexed to the Portuguese territory.

Having acquired the Kotte and Sitavaka kingdoms and with only Vimaladharmasuriya 1 (CE 1592-1604) the King of Kandy to deal with, the Portugese expelled the Moors from Sitawaka. They had also settled down in the port towns of Negombo, Puttalam, Beruwela and Alutgama.

Hour of distress

The attempted extermination of the Muslims by the Portuguese and later by the Dutch, commenced their infiltration to the Kandyan Kingdom from the Western Province where awaited a hearty welcome by the upcountry rulers especially that of King Senarat (CE 1604-1635.) Thus, the last bastion of independent Buddhism, became a haven for the Muslims in their hour of distress where they were allowed to practice their religion without hindrance from the Portugese. This commenced the indigenisation of the Muslims.

The Kandyan kingdom in turn, being denuded of manpower following the continuous wars, needed people to develop agriculture and strengthen the economy. Being traders, Muslims also had access to the Ports, links with the outside and therefore were knowledgeable on matters of the world. Muslim villages thus sprang along trade routes to Kandy and in the interior where Kings had given them grants of land.

Having encouraged the Muslims to maintain their links with the Islamic world, the King found them useful informants of international affairs. A state of harmonious co-existence as a result, unique in an era of religious persecution and rivalry, developed in Sri Lanka.

Arab authors have recorded that the Royal court of Sri Lanka was particularly noted for its religious tolerance. Idrisi in the 12th century had mentioned of a Council of 16 set up at the Royal Court consisting of 4 Buddhists, 4 Muslims, 4 Christians and 4 Jews. The interests of the rulers were closely integrated with those of the Muslims and hence the latter’s advice was readily accepted. It is also possible, the author suggests, that the trade missions sent to the Arab world by the King was a cover to seek an alliance with the Muslim world to counter the constant threat of invasions from South India.

Dr. Dewaraja makes the point that the Muslims on their part, while rendering service, never attempted to arrogate political power on themselves. They were respectful of state authority and were sensitive to the susceptibilities of the Sinhalese. Hence, although they arrived as refugees, they were well received at the Kandyan Court. Queros writing of Senarath’s action said “in Batticaloa, the idolatrous king, placed a garrison of four thousand of them, thus showing his mind by favouring our enemy.”

Senarath’s settling of the Muslims in the fertile lands around Batticaloa, resulted in the quick recovery of the kingdom following the invasions of 1628 and 1630. The largest rural Muslim settlements to this day are in the Batticaloa area and they have earned the reputation of being some of the best farmers in the country.

Particularly adroit at diplomacy, the King in turn, depended on their services with regard to information of foreign visitors who arrived at the Trincomalee port. With their linguistic fluency – being able to speak Tamil, some South Indian languages and even Portugese, they kept the King well informed of trade and power politics operating globally while acting as virtual ambassadors. The author’s findings during her research include a few Muslim families in the Kandyan areas bearing the family name of “Tanapathilage gedera” (home of the ambassador.)

22 Dec 2024 1 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 1 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 4 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 4 hours ago

21 Dec 2024 21 Dec 2024