16 Mar 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Fear and panic are all present the world over. As communities shrink under the weight of the Coronavirus, the global economy is grinding to a halt. What does this time of pandemic mean for our society? How does the process and priorities of economic development and the character of democratic culture in a country relate to the impact of natural disasters such as the Coronavirus?

The current juncture where the country is at the crossroads socially, economically and politically, is a moment to look back at our past as we think about our future. The significant changes in Sri Lanka during the late colonial period provide some important insights for our present predicament.

One entry point into that history are the reports of the Donoughmore and Soulbury Commissions. And this is what the Soulbury Commission Report of 1945 had to say about the Donoughmore Commission and the implementation of its recommendations starting in the early 1930s.

“It is necessary, therefore, to inquire how far the hopes based on the grant of adult suffrage have been justified since 1931. The franchise in itself does not awaken a general social consciousness, particularly when it is given without previous agitation for it. … Social legislation involves expense. In justice to the State Council it must be remembered that it came into office at a time of acute and world-wide economic depression. This had serious repercussions in Ceylon, for, as dependent as it so largely is on the export of three agricultural products—tea, rubber and copra—the collapse of world markets inevitably involved much distress. Hardly had signs of recovery shown themselves when the failure of the South-West monsoon in 1934 brought new disaster. The shortage in the food crops meant famine over wide areas. This was followed by the most severe malaria epidemic in recent years, which lasted from the autumn of 1934 to the summer of 1935, and relief measures had to be undertaken on an extensive scale. For these reasons there was an urgent call for extraordinary expenditure at a time when the revenue showed a considerable shrinkage.”

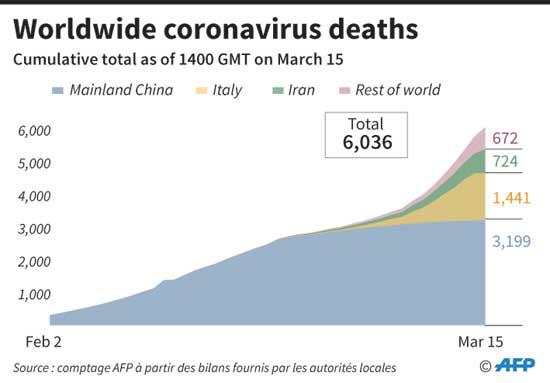

The 1930s as recorded by the Soulbury Commission seem worryingly similar to how someone may record our last decade of history say five years from now. Sri Lanka’s economy has been crippled by the fall out of the global economic crisis of 2008 and the long droughts and floods that have devastated agricultural production over the last many years. Furthermore, the declines government revenues and foreign exchanges earning not only relate to the fall in the tea, rubber and coconut industry, but also the lower inflows of migrant workers remittances, and the drop in the garment sector and the tourism sector, which have all been affected by instability in the global economic order. And when considering the possible fall out of the Coronavirus pandemic, one is reminded of the malaria epidemic some eighty five years ago, which affected close to a million people. And as with the years before Independence troubled by high state expenditure compared to revenues and falling foreign earnings, the country is again now affected by twin crisis of fiscal deficit and balance of payment problems.

The Soulbury Commission, however, also recognised some of the significant advances during that period building on democratisation with universal suffrage. It went on to argue that “one of the most noteworthy and commendable achievements of the Government of Ceylon during the last decade has been the development of the social services, including health and education.” Without doubt, free education and healthcare policies have greatly strengthened Sri Lankan society to this day.

Looking at the current policy environment, the colonial authorities’ views as reflected in the Soulbury Commission Report are much softer than what the current day imperial monitors, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), may force on Sri Lanka. There is unlikely to be any respite to address the current economic crisis, as privatisation and cuts to state expenditure are  likely to be the same old conditions that will be imposed if SriLanka requests support from the IMF.

likely to be the same old conditions that will be imposed if SriLanka requests support from the IMF.

As for the neoliberal pundits who preach a sole economic path forward of connecting to global supply chains, the current global crisis with unravelling supply chains should be a rude awakening. Indeed, this is the moment to dump the grandiose neoliberal claims of export led growth. Self-sufficiency in essential goods are important, precisely given these types of crises. After all when global markets fail with panic and disruptions, the citizenry and their economy, have no recourse but to demand solutions from their governments.

Sadly, as the global economy contracts, Central Banks and policy makers around the world are resorting to the same old tools of monetary policy that are unlikely to work during this massive crisis. John Maynard Keynes, whose economic thinking gained ascendency during the Great Depression of the 1930s, criticised monetary policies for precisely these failings. He claimed, that while an overheating economy can be slowed by pulling it down with a string, the same does not work for a contracting economy where it will be like pushing on a string to expand the economy. In other words, cutting interest rates or increasing the money in circulation cannot address a deep economic downturn. This is even more so during a crisis such as the one with a pandemic, where it will amount to building the confidence of producers and consumers by blowing hot air of policy speak.

The reality is that a major part of the reason for the current melt down of the global economy are its shaky foundations of a capitalist economic system made further fragile by four decades of its latest phase called neoliberalism. This situation is not an aberration, but rather a systemic surrendering of the economy to the market in the interest of the profits of the wealthy, and that has made our societies and economies vulnerable. The great inequalities created by this global class project of neoliberalism affects the working people the most during crisis times. It is the informal and day wage workers, and the working classes more broadly, that will be devastated when society breaks down with a pandemic.

In Sri Lanka, we should be first of all grateful for our free healthcare system, despite decades of elite efforts to dismantle free healthcare it has survived at least in its current form. However, our social welfare system did not emerge out of nowhere. While the Colonial Commissioners don’t mention it, in reality that ethos of welfare came out of the Suriya-Mal movement, which mobilised youth to act on the malaria crisis, and was also the beginning of a Left movement in Sri Lanka back in 1935.

In the year ahead, Government revenues are going to fall and economic policies are going to fail, and it is again a major challenge before progressives to think of ways of mobilising society. The chauvinists will also mobilise, but that will be to polarise people, to find scapegoats among minorities and xenophobia to blame others for this pandemic, rather than look at the essential flaws in our economic and political system. For progressives, ensuring food security, healthcare and the essentials of life are going to be the priority. With an existential challenge before us, co-operation among people and the spirit of economic democracy is the need of the hour.

25 Oct 2024 2 hours ago

25 Oct 2024 4 hours ago

24 Oct 2024 7 hours ago

24 Oct 2024 7 hours ago

24 Oct 2024 7 hours ago