14 Sep 2019 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Although the smallest of the three major oceans, the Indian Ocean has been growing in geo-political significance. Asian countries accounted for more than 60 per cent of world economic growth last year. The redistribution of power in the world is most evident in this ocean, and today, the Indian Ocean is central to global politics and the economy. This has caused more disputes and militarisation involving extra-regional powers, prompting calls for an order or institution specific to the Indian Ocean to combat such regional security concerns.

The Bandaranaike Memorial Oration, organised by the Bandaranaike Centre for International Studies (BCIS), was held on September 6. Making the welcome address, BCIS Council Member Prof. Amal Jayawardena dedicated the oration to the 60th death anniversary of former Prime Minister S.W.R.D Bandaranaike. The event ended with the presentation of the publication ‘Anura Bandaranaike: Legacy in the Legislature’ edited by BCIS Deputy Director George Cooke.

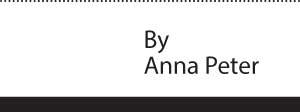

BCIS Director Dr. Harinda Vidanage introduced the keynote speaker, former National Security Advisor, Foreign Secretary and Indian Ambassador Shivshankar Menon, who spoke on the topic, “Emerging International Order in the Indian Ocean”.

Addressing those present, Mr. Shivshankar Menon mentioned S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike’s contribution to developing Sri Lanka’s foreign policy. He said Sri Lanka was able to successfully navigate the “pulls and pushes” of power rivalries and politics in the 1970 due to the foreign policy legacies of its founding fathers, including S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike.

He said efforts to codify the law of the sea, resulting in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) caused a shift in the power balance. “This brought a semblance of order to maritime law, and contributed directly to a wave of globalisation in the ‘80s and ‘90s that raised unprecedented numbers of people from poverty in Asia,” Mr. Menon said.

He said the balance of power was shifting again as the Indian Ocean and Asia became more militarised due to technological and economic changes. Mr. Menon mentioned three areas in this regard. First, the events and circumstances that led to the present, second, the existing order or the lack of it, and finally, the future of the Indian Ocean world.

Historical developments in the Indian Ocean

Historical developments in the Indian Ocean Mr. Menon observed that the Indian Ocean’s open geography made it peaceful for trade. Historically, migration and travel had impacted the politics of the Indian Ocean world. In the late 19th and early 20th century there was a brief low point in the ocean’s global significance. But as great powers again made moves to militarise the Indian Ocean, rivalries and disputes increased. “As the significance of the Indian Ocean increased human global economy, it became an increasing stage for great power contention. Globalisation empowered new actors and shifted the balance of power. Asian waters, therefore, became critical and crowded seas,” Mr. Menon said.

Furthermore, economic growth has enhanced Asian power interests in the sea, making freedom of navigation and sea-lane security critical factors. “We depend on the rest of the world and on the Indian Ocean to carry energy, commodities, and to provide the technology and connections to markets and food,” Mr. Menon said. “Today the Indian Ocean it is central to global politics and the economy. The redistribution of power in the world is most evident in this ocean. Last year Asia countries accounted for more than 60 per cent of world economic growth. India and China together accounted roughly for the same GDP as the US, which is a huge shift and enhances the significance of the Indian Ocean.”

Mr. Menon identified, India, China, Japan and Korea as the powers most dependent on the Indian Ocean for their growth and prosperity. What used to be regional issues have now become global issues. Using the example of piracy, Mr. Menon contrasted how piracy was tackled regionally in the Strait of Malacca, with how it was combated off the Horn of Africa involving 28 navies. He added that deteriorating US-China ties had increased the Indian Ocean’s significance to the US, marking a shift in their maritime strategy.

Discussing competing visions of order in the Indian Ocean and Asia, Mr. Menon, identified one as a free and open pacific, and the other as the belt and road initiative. While these were different approaches, he said neither strategy seemed equipped to deal with immediate security problems. “Given arising contentions and the militarisation of the Indian Ocean, can we speak of an order in this area, and could an order emerge?” he asked. “For me the realistic prospect is for the significance and attraction of the Indian Ocean to increase, for outside powers to be involved, and for neither of these competing visions to prevail in the region. We seem to be in for a period where no single actor or group of actors, external to the Indian Ocean will be able to impose order.”

He further urged Indian Ocean countries to “take their fate into their own hands”, adding that an effective regional strategy should address security issues in an increasingly militarised Asia.

Although politics in Indian Ocean countries was growing more polarised, making diplomacy and negotiations harder, Mr. Menon asked why in the absence of an order and institution there had been an extended period of peace. “It seems that the security interest of the states increasingly coincides, whether it is in maritime security, cyber security or counter terrorism,” he said, adding that the ideal way to channel such common interests was to form issue-based coalitions among willing States. “Any successful order needs to have an economic basis. If we are to maintain order in the ocean, we must do more to integrate the economy of countries in the Indian Ocean world,” he emphasized.

Given the balance of power and open geography, the freedom of navigation was not at risk, a crucial factor to trading nations. Even though economic integration was weak, the Indian Ocean world is one of the fastest growing regions. “It is integrating, and is increasingly linked to South East and North East Asia. Much of the political instability is not only externally induced, but also a result of how we handle our own domestic politics,” Mr. Menon said.

He pointed out that the lack of security alliances and structures was both a strength and weakness. “It allows us to respond pragmatically when we see a problem, like when dealing with piracy. It is a weakness in that responses are unpredictable and would depend on who is in power and their state of mind, which is not a reliable basis for the future,” he said.

In conclusion Mr. Menon expressed optimism regarding the direction and progress in the Indian Ocean world. “The Indian Ocean world has the historical experience and has displayed the wisdom necessary in the past to manage its affairs more often than not. What our region does possess richly, is a practical ethic of co-existence. If we can do it again in the future, we can prove the prophets of doom wrong,” he concluded.

22 Dec 2024 18 minute ago

22 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 5 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 5 hours ago