14 Mar 2024 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The recent snub by the SJB and JVP to attend a meeting with the IMF delegation raises concern about the country’s uncertain political future, where political parties thrive in harnessing public anger rather than offering solutions

You could see the shades of all in the recent snub by the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) and Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) to a president’s invitation to attend a meeting with the IMF delegation in Colombo. They were offered a forum to raise their objections, which you usually hear in press conferences and political meetings, and present a coherent alternative plan

This political grandstanding is nothing more than benefitting from the country’s misery. When even a remotely cohesive nation is faced with an existential crisis, its disparate stakeholders momentarily set aside their differences. The survival of the state takes precedence over everything else.

For a recent example, consider Israel, where political opposition has joined a war cabinet and people of the Left and Centre who loath Benjamin Netanyahu and his ultra-nationalists have come together since the brutal terrorist attack by Hamas. Israel’s conduct of the war in Gaza could well be questionable, but that it is faced with an existential threat is real.

For a recent example, consider Israel, where political opposition has joined a war cabinet and people of the Left and Centre who loath Benjamin Netanyahu and his ultra-nationalists have come together since the brutal terrorist attack by Hamas. Israel’s conduct of the war in Gaza could well be questionable, but that it is faced with an existential threat is real.

Now consider Sri Lanka. We are still in the throes of an acute crisis. Two years back, it was an existential crisis that threatened the state’s very existence as a cohesive and functioning unit. This is not an exaggeration. An acute economic crisis could break a country beyond repair, partly because such a malady is not the disease itself, but a symptom of a much larger chronic sickness encompassing politics and society. For Sri Lanka, which prevailed over a nihilistic separatist terrorist campaign only 15 years ago, the collapse of the Centre could well have augured the deconstruction of the country itself. Ethiopia split into two in a similar way when the Centre lost its grip, and since then, has existed in an eternal state of war with its new patricidal neighbour Eritrea and a constitution that amplified ethnic differences in the name of ethnic federalism, weakened the Centre, and now militias of each region are killing each other at a free for all mayhem.

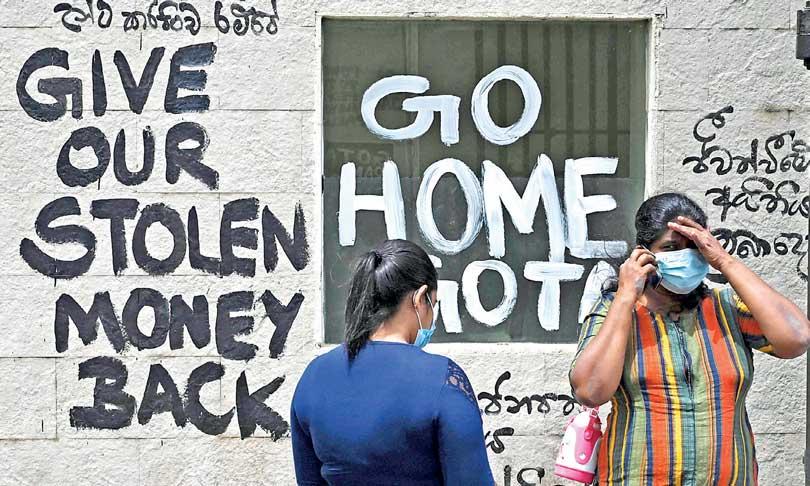

Sri Lankans of all walks of life came together to protest the government of Gotabaya Rajapaksa, whose egoistic and idiotic economic management created the worst-ever economic crisis since the independence.

But did politics come together?

Their early vacillation can be excused, for their options were limited at that time. The public anger was directed not just against Rajapaksas but also against the traditional political establishment. If anyone deserves credit for solving the early phase of the political crisis, which could have turned bloody in most parts of the world, it was the man who created the crisis itself, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who resigned and left the country.

The political differences in Ranil Wickremesinghe’s appointment as president were also understandable, considering his dependency on the Pohottuwa. A good number of people wanted a clear break from the Rajapaksas and anything they touched.

However, in retrospect, a search for a ‘better’ candidate or a group could only have been possible, contravening the constitutional process of leadership succession. Any individual appointed through extra-constitutional means would then have to be protected through extra-constitutional means. Worst still, there is a good chance of such individuals being self-righteous imbeciles with little practical competencies.

Assume we grant a generous allowance for all the differences in the past, considering the existential circumstances at the time. But what explains the reluctance of political parties to come to a common agenda now?

Sri Lankan politics suffer from a strong sense of self-seeking opportunism that prevents the country from forging a common goal. This malaise manifests in various forms. First is in the form of feigned dementia about the perilous state of the country just two years back.

Second is a stubborn refusal to acknowledge that the country had made great strides out of the nadir of economic crisis, though it is not out of the woods.

Third is a sinister desire to see the incumbent fail, regardless if that would also mean the country’s failure as a whole.

You could see the shades of all in the recent snub by the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) and Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) to a president’s invitation to attend a meeting with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) delegation in Colombo. They were offered a forum to raise their objections, which you usually hear in press conferences and political meetings, and present a coherent alternative plan. (Interestingly, the offer came after a request by SJB MP Harsha de Silva, though he now claims he asked for a meeting with the bond holders and not the IMF.)

Now, such is the low expectations of the public in their elected representatives that most Sri Lankans would not consider this conduct a betrayal of public trust. Many might even take their flimsy excuses seriously, that might be an ad-hoc measure of limited political literacy of a country that prides itself as Asia’s oldest democracy.

That ignorance, as well as low expectations of their political representatives, are dangerous. They foster opportunism in their political classes.

It would not have cost anything for the SJB or the JVP to attend the meeting with the IMF to present a unified face of the political classes to the world. However, petty personal and political calculations took precedence over the country. This is not just a show of pettiness in Sri Lankan politics. This sends wrong messages to the would-be investors and amplifies concerns about political instability in the country and its implication on the economic recovery process.

This political grandstanding is nothing more than benefitting from the country’s misery.

This is also a dangerous gamble for its partakers, especially for the SJB. It has relegated itself to become a mirror image of the JVP, historically thrived in the nation’s tragedy when it did not unleash the public’s misery.

This also raises concern about the country’s uncertain political future, where political parties thrive in harnessing public anger rather than offering solutions. Hence, Sri Lankans should be very worried.

Given the Sri Lankan penchant for misadventure, it is difficult to vouch that the country would not repeat the blunder akin to electing Gotabaya Rajapaksa. But one thing is also increasingly clear. If the country crumbles for a second time, the public will not give an easy way out to the elected leadership, as Gotabaya Rajapaksa had. They would make a Ceausescu at the collapse of communism in Romania.

Follow @RangaJayasuriya on X

25 Nov 2024 58 minute ago

25 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 3 hours ago