03 Nov 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

America’s Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, who was in Colombo, making the second stop in his four-nation Asian tour slighted China as a predator, last week.

America’s Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, who was in Colombo, making the second stop in his four-nation Asian tour slighted China as a predator, last week.

“We see from bad deals, violations of sovereignty and lawlessness on land and sea that the Chinese Communist Party is a predator, and the United States comes in a different way, we come as a friend, and as a partner,” he told a media conference winding up a 12-hour Sri Lanka visit.

Are China’s loans to the developing world predatory and exploitative by design - a ‘debt trap diplomacy’? It is not easy to find a uniform answer. China is investing in a wide variety of states, including some of the least salubrious, kleptocratic and nepotistic. Generally, domestic conditions tend to influence the lender’s behaviour, especially when the latter itself does not have a hard and fast code of conduct or domestic regulatory mechanisms that hold it accountable. Add to that is Chinese loan conditions are opaque.

But, for the specific case of Sri Lanka, the answer might be straight forward.

But, for the specific case of Sri Lanka, the answer might be straight forward.

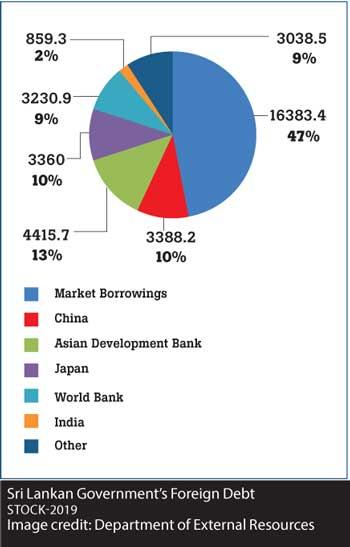

Sri Lanka is obviously in a debt trap. The external debt stock of the government at the end of 2019 amounted to US$ 34.7 billion. In addition, State-Owned Enterprises and other semi government entities had borrowed US$ 21 billion using sovereign guarantees, making the government liable for repayment. Effectively, the total foreign debt of Sri Lanka is US$55.9 billion, which accounts for 66.6% of GDP at the end of last year.

However, China’s share in the government’s external debt is 10%, i.e. equivalent to Japan’s. The largest lender, ADB owns 13% and the World Bank 9% (Department of External Resources). This is not where the debt trap is set in. 47% of the government’s foreign debt is in market borrowing, taken through the issuance of international sovereign bonds (ISBs). Unlike the bilateral or multilateral loans, which are obtained at concessionary interest rates with a longer period including a grace period for debt repayment, sovereign bonds are issued at the commercial rate - around 6-8% - and have a shorter repayment period. Rolling-over of sovereign bonds has caused immense financial distress, leading to successive governments to issue fresh bonds to repay the ones that had matured. Last year alone, the government raised US$ 4.4 billion, through the two issuances of ISBs while repaying sovereign bonds worth US$ 1.5 billion, also in two repayments. Primarily due to this, the outstanding liability of sovereign bonds rose to US$ 15.2 billion at end 2019 from US$ 11.6 billion in the previous year, according to the Central Bank accounts. Within this year alone, Sri Lanka has to pay US$ 4.8 billion as external debt repayment, much of which to matured ISBs. That is also the largest debt repayment in the country’s history.

To make matters worse, concerns over the country’ repayment ability have dulled investor confidence. Sovereign bond auctions in March were poorly subscribed, leading the government to shelve plans for future issuances anytime soon. That would probably save the future taxpayers, momentarily, but it has further deteriorated the government’s fiscal position.

Chinese loans aren’t the catalyst of Sri Lanka’s debt burden, but the poor fiscal management, meagre export revenue and low FDI etc. Like other bilateral loans, the overwhelming portion of Chinese loans (over 80%) is obtained at concessionary terms. One would even argue that the Chinese development assistance provides a cushion for the government that is deep in a debt crisis. They address the much-needed infrastructure development needs.

However, given Beijing’s style of no-string attached lending, Chinese loans are more likely to be spent on vestige projects and pilfered away by the corrupt leaders. Which is much harder to do with other bilateral or multi-lateral loans, say for instance the Japanese, ADB or World Bank. Mahinda Rajapaksa as the President ploughed Chinese loans into an airport, port and an international conference centre - all in his home turf - with little or no economic viability. The second phase of the Hambantota port was financed by China at the commercial rate.

China’s willing partners across the world are a motley group. Some such as Angola’s ex-ruler Dos Santos, DR Congo’s Kabila, rulers of Zambia are in a different league altogether. Such partnerships, needless to say, is reeking of corruption and nepotism while population live in the squalor.

Sri Lanka is obviously in a debt trap. External debt stock of the govt at the end of 2019 amounted to US$ 34.7 bn. In addition, State-Owned Enterprises and other semi govt entities borrowed US$ 21 bn using sovereign guarantees. Effectively, the total foreign debt is US$55.9 bn, which accounts for 66.6% of GDP at the end of last year

Over dependency on China could also make Beijing more demanding. That can happen when the local political rulers prefer to go to Beijing with the begging bowl, instead of reaching out to other lenders who might demand greater accountability and better fiscal management. Sri Lanka is also negotiating a second loan of US$ 700 million, on top of a previous US$ 500 million, from China, rather than opting for a hard reform programme with the IMF.

Over dependency on China could also happen when the world’s democracies shun a country for its worsening human rights records, which had partly been the case with the second term of the MR administration.

Nonetheless, the visit by the US Secretary of State, and America’s geo-political interest in the Indian Ocean provide Sri Lanka with an opening to diversify its economic partnership. Not least because the United States is Sri Lanka’s largest export partner.

Sri Lanka should not let domestic political calculations and other usual antics to fritter this opportunity away.

Wimal Weerawansa, the government Minister and a stalwart of the ruling family says Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa was not keen to meet Pompeo. The international press reported MR as having snubbed the the visiting US envoy. The Prime Minister’s office has since rebutted the claim. Though whether MR or his acolytes think he was doing a favour to America by meeting the Secretary of the State of the world’s most powerful country is a different story.

America and its democratic allies can address a hole in Sri Lanka’s partnership with China. Though China had helped putting up hardware, the physical infrastructure, it has not done much, nor is it likely to achieve much - by putting in place the software of development. Technology transfer, technological and investment clusters, development of human capital, etc do not count much in China’s economic role in Sri Lanka. The United States is the world leader in all of that. That is exactly why 400,000 Chinese students go to American universities - and probably why Gotabaya Rajapaksa sent his only son to Duke. The rise of East and South East Asian technological powerhouses was made possible by more than anything else the economic and technological cooperation with the US. The current systemic opening may not be as decisive as it was during the height of the bipolar rivalry, but, this is an opportunity worth giving a shot, nonetheless.

That does not mean giving up on China, but diversifying economic relations and optimizing opportunities.

Follow @RangaJayasuriya on Twitter

30 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 5 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 6 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 9 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 30 Nov 2024