15 Sep 2021 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

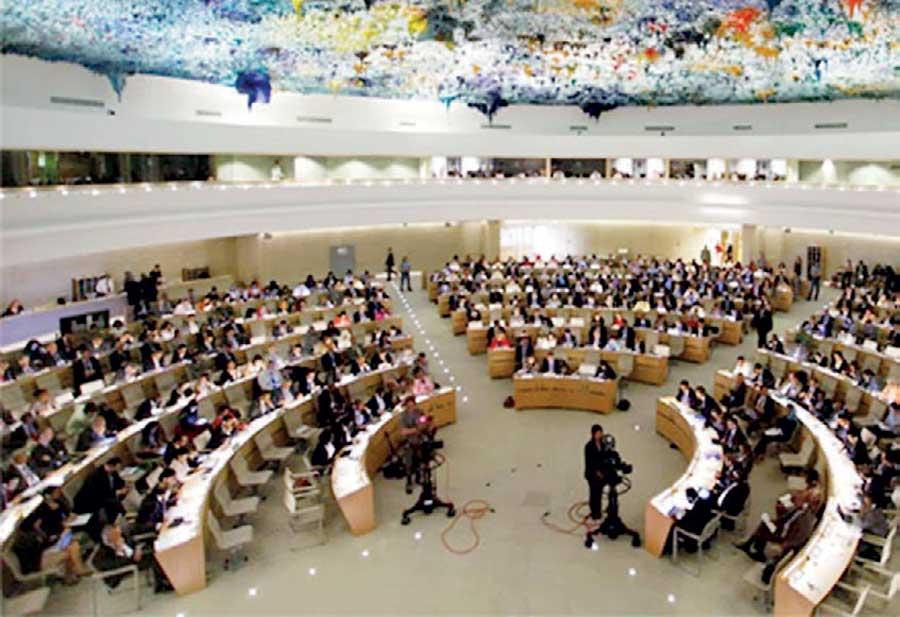

As the Sri Lankan Government contends with urgent economic and public health crises, the specter of the 48th session of the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) hangs over it. Recent sessions have emphasized Sri Lanka’s short-comings in the context of previous commitments. A January 2021 UN report “warns that the failure of Sri Lanka to address past violations has significantly heightened the risk of human rights violations being repeated. It highlights worrying trends over the past year, such as deepening impunity, increasing militarization of governmental functions, ethno-nationalist rhetoric, and intimidation of civil society”.

session of the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) hangs over it. Recent sessions have emphasized Sri Lanka’s short-comings in the context of previous commitments. A January 2021 UN report “warns that the failure of Sri Lanka to address past violations has significantly heightened the risk of human rights violations being repeated. It highlights worrying trends over the past year, such as deepening impunity, increasing militarization of governmental functions, ethno-nationalist rhetoric, and intimidation of civil society”.

"Sri Lanka currently faces an uphill battle to convince the international community that it will pursue justice and reconciliation in good faith. Resolution 46/1 of March 2021 called for establishing a mechanism to “collect, consolidate, analyze and preserve information and evidence and to develop possible strategies for future accountability processes for gross violations of human rights…”

Sri Lanka currently faces an uphill battle to convince the international community that it will pursue justice and reconciliation in good faith. Resolution 46/1 of March 2021 called for establishing a mechanism to “collect, consolidate, analyze and preserve information and evidence and to develop possible strategies for future accountability processes for gross violations of human rights…”

One should not ignore the obvious geo-political currents or well-versed and deeply entrenched pro-LTTE, separatist propaganda perpetuated by the Diaspora as key factors driving multi-lateral manoeuvres concerning Sri Lanka. Yet accusations of theage-old western liberal double-standard notwithstanding, it is worth reflecting on a crucial period of Sri Lanka’s diplomatic history at the UNHRC.

Gap in Popular Culture

There was a concerted effort by mostly Western powers through much of the 2000s to re-establish the 2002 Cease-fire Agreement (CFA). The EU, in particular, with the UK in tow, through various resolutions including those passed in 2006 and 2009, had consistently called for a return to negotiations with the LTTE. As the Sri Lankan military prepared for what was to be the final phase of the war in early 2009, the EU pushed for a ‘Special Session’ of the HRC to establish a ‘humanitarian pause’ to the conflict, allowing a return to peace negotiations as well as an independent investigation into possible war crimes.

Journalist and author Sir Simon Jenkins criticized the then UK Foreign Secretary David Miliband for his attempted interventions, noting that a ceasefire at such a late stage would have been a gift to the LTTE as well as diluting Sri Lanka’s costly, hard-won military gains ofprevious years.

In 2007, Dr. Dayan Jayatilleka was appointed as the Permanent Representative of Sri Lanka to the United Nations in Geneva. Writing in ‘War, Denial and Nation Building’, Rachel Seoighe recounts Dr. Jayatilleka’s instructions to his staff that included references to the Battle of Thermopylae whereby the 300 Spartans had provided military cover for the Greek Federation to mobilize political support. Dr. Jayatilleka had acknowledged the fact that a session on Sri Lanka was inevitable but emphasized that, in delaying the session and thereby any premature agitation for a ceasefire, the military would have the time and space to complete the mission on the Northern front.

Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha was then appointed as Secretary-General of the Sri Lankan Government Secretariat for Coordinating the Peace Process and proved a useful ally to Dr. Jayatilleka and his efforts in Geneva. Through even casual viewing of Prof. Wijesinha in interview mode, one cannot fail to notice his fierce and commanding grasp of asubject and the rhetorical style utilized in articulating a point. Prof. Wijesinha was noted by US officials for his aggressive stance on statements made by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights at the time, Ms. Louise Arbour. Being one of Sri Lanka’s more prolific English language authors, Prof. Wijesinha’s most recent book: ‘Representing Sri Lanka: Geneva, Rights and Sovereignty’ (2021), is an excellent commentary on this period. He credits Dr. Jayatilleka for altering the course of Sri Lanka’s destiny at the UNHRC by utilizing what Gerrit Kurtz (Protection in Peril) describes as discourse with a three-pronged foundation of counterterrorism, humanitarianism and anti-imperialism/ self-determination. There was a focus on protection, making use of and even building on the solidarity of the global South.

"One notable aspect of this process involved organizing events structured in ‘debate mode’ with wide discussion on all aspects of the Sri Lankan issue by Dr. Jayatilleka and his specifically curated group of emissaries that included Prof. Wijesinha but also Ms. Shirani Goonetilleke and Dr. Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu"

A Wikileaks cable makes clear that Sri Lanka had effectively utilized its position as a founder member of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM): “As in the past, Sri Lanka’s delegation took a tough and often acerbic tone in its latest public relations campaign in Geneva. While this may in part reflect the personality of its ambassador in Geneva, Dayan Jayatilleka, it also reflects a strategy of appealing to NAM countries, to whom it argues implicitly (and probably explicitly, behind closed doors) that it is willing to stand up to the West, which is unfairly picking on it. That message resonates particularly strongly in the Human Rights Council, further complicating our efforts to use that body to pressure Sri Lanka on its human rights record.”

There is an under-appreciation within Sri Lanka of the intricate and focused diplomatic operation carried out by Dr. Jayatilleka and Prof. Wijesinha along with the Sri Lankan Mission, leading up to and during the 2009 sessions. The scholarship seeks to plug this gap in popular culture with a variety of internationally published research and analysis providing fascinating insights into the successful Sri Lankan diplomatic battle of 2009. Kurtz recognized Sri Lanka’s diplomatic efforts and the “three-pronged discourse” as a means to generate what Dr. Jayatilleka calls ‘strategic counter hegemonic resistance’.

Seoighe remarks that Sri Lankan representatives in Geneva were successful in challenging the ‘liberal humanitarian norms’ of the UN system and refers to Sri Lanka’s dialogue on what constitutes global norms within the UNHRC and the wider international system. Sri Lankan diplomats were considered ‘norm entrepreneurs’ forarguing that the UNHRC was “a forum for contesting, rejecting and adapting norms rather than merely perpetuating the liberal norms on which the institution was built”.

David vs the Global Goliath

One notable aspect of this process involved organizing events structured in ‘debate mode’ with wide discussion on all aspects of the Sri Lankan issue by Dr. Jayatilleka and his specifically curated group of emissaries that included Prof. Wijesinha but also Ms. Shirani Goonetilleke and Dr. Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu. All relevant actors were invited to attend, including those most critical of Sri Lanka: Amnesty International (AI), Human Rights Watch (HRW) and various NGOs and pro-LTTE representatives. This inculcated a spirit of open dialogue which was praised by the US mission and one speculates that oppositional elements were simply out-gunned by the depth and intellectualism of the Sri Lankan delegation.

The results were stunning; the eventual Resolution S-11/1 was fundamentally supportive of the Sri Lankan government and was the result of a carefully crafted campaign to build a consensus, a realization even, amongst members of the HRC. The global South and the NAM would accept that Sri Lanka’s position in 2009 was far more complex and delicate than the western liberal narrative suggested.

Resolution S-11/1 passed with 29 votes in favour with only 12 opposing it and 6 abstentions. It would not refer to a war crimes investigation and even praised Sri Lanka’s many commitments and efforts at rehabilitation, reintegration and resettlement. This 2009 resolution represented nothing short of complete defeat for the western group including the EU and the UK.

Casual observers oftenreflect on the steadfast resolve of President Mahinda Rajapaksa throughout the final phase of the war, in the face ofmounting international pressure from western and even Indian leadership to halt the offensive.What they are partly and unknowingly alluding to are the aforementioned, crucialefforts of Sri Lankan diplomacy, which warrants wide appreciation in any considerationof Sri Lanka’s victory over the LTTE. Unfortunately, the diplomatic gains of 2009 following the military victory have since been diluted by a cocktail of diminishing returns from two sources. First, the markedly less acerbic discourse by the country’s subsequent emissaries in Geneva and beyond. Second, the Sri Lankan Government’s own failure to live up to itscommitments to the international community.

Double-Edged Swords and Double Standards

The Cambodian Genocide that occurred between 1975 and 1979, led to some 2 million deaths. Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge, financially and militarily backed by the Chinese Communist Party, had perpetrated one of modern history’s most notorious mass crimes. The 2006 Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), better known as the Cambodia Tribunal was responsible for successful indictments and convictions in several cases of senior members of the Khmer Rouge. This Tribunal is a national court, consisting of local and foreign judges including Sri Lanka’s Nihal Jayasinghe, former UK High Commissioner and senior presiding judge of the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka, making the ECCC a “hybrid court”.

Sri Lankans will be familiar with the concept of a hybrid court as this is considered one of the more controversial aspects of the UNHRC Resolution 30/1 of 2015 that was co-sponsored by the Yahapalanaya administration of the time. Item number 6 on the resolution “…affirms in this regard the importance of participation in a Sri Lankan judicial mechanism… of Commonwealth and other foreign judges… and investigators”.

Sri Lanka has made immense progress on rehabilitation and resettlement while also opening the Office on Missing Persons in 2017 and the Office for Reparations in 2018. However, tangible progress on transitional justice mechanisms and political solutionshas proved elusive and a more recent failureto engage at homeleaves Sri Lanka exposed to further criticism. As President in 2009, Mahinda Rajapaksa committed to implementing the 13th Amendment to the constitution; this was enshrined in the 2009 resolution.

Sri Lankans are not blind to the western double standard, not even the ever-expanding segment of liberals that have grown up amongst the trans-culturalism of cities in the western province. There is also an anti-imperialist streak among Sri Lankans that reject the multilateral world order. The media will always cover an issue in black and white, with an oppressor/oppressed narrative. The academic writing fortunately appreciates the intricacies of the Sri Lankan calculus as well as holding balanced and sober views on the challenges posed by the LTTE and what an acquiescence to its well drilled propaganda machine means for future conflicts against similarly well-organized terrorist outfits.

Essential Display of Diplomatic Integrity

Sri Lanka, for its part, must recognize the roots of the HRC, as an institution that promotes fundamental human rights, while understanding its 1967 evolution into interventionism morphing into the existing culture of condemnation and investigation. This evolution was a result of the de-colonization period when nation states, including many from the global south, began to assert themselves through the UN to bring justice for egregious violations during centuries of imperial conquest.

The critique of neo-liberalism is now widely discussed in Sri Lankan discourse and has predictably enmeshed itself with, some would say co-opted by, the lurking suspicions many Sri Lankans share of multilateral organizations, NGOs and western actors in general.

Whether one agrees with these critiques, Sri Lankans must acknowledge the benefits of access to western markets, a result of continuous liberalization of the global economy which necessitated the formation of rules based, institution driven relationships between states. Take the ADB, World Bank and even JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) which have funded Sri Lankan roads and expressways or the EU’s GSP-Plus; these are all interventions that are part of the same system of global order as the UNHRC. Sri Lankans cannot be selective on what part of the global system it wants to engage with. This cannot be achieved without the present regime confronting itself on the issue of the 13th Amendment.

While a critique of western double standards is necessary, it should not prevent Sri Lanka fromengaging in global systems. A power deficit alone is not reason enough to retreat, as Dr. Jayatilleka’s King Leonidas revealed. Sri Lanka, instead of being dismissive of the UNHRC and the triangulations of the western group, must once again substantively argue its casefrom a positon of unflinching integrity.

The writer is reading for a PhD in International Relations at the University of Colombo and has 15 years experience in the banking industry and travel sector as well as being a student of International Relations and American Politics with a Master of Arts Degree from the University of Colombo and a Joint Honours Bachelor’s Degree from the University of Kent.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @kusumw

28 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 6 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 7 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 8 hours ago