13 Jul 2021 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A large proportion of the scientific community has clearly stated that without inorganic fertilizer, our agricultural system will not be able to sustain itself, resulting in a severe food crisis and an increase in rural poverty. First, I support this collective observation as it is based on science. However, I started to explore further and compare what we see today and what I saw during my journeys sightseeing around the island in the 1960s. I remember observing an almost 6-inch-deep cow dung layer in villages around Sigiriya, Polonnaruwa, Anuradhapura, Batticaloa, Ampara, Panama, Moneragala, Hambantota and Madu areas. These were collected by Jaffna farmers by the truck load. People in those areas have the habit of digging pits and mixing cow dung with the soil. So, the whole landscape was pockmarked with these pits. This may be to break the hard-top layer to enable water to enter the ground so to collect seasonal rain. This prevents unused water from washing away the fertile soil and seeds. Finally, it allows seed germination and plant growth. Historically, large herds of cattle, buffalo, and goats roamed the entire country’s landscape, including pasture lands, shrub areas, and abandoned chena lands. These pastoralists have for centuries been in the habit of stocking pasture lands, shrub areas and abandoned chena lands with their herds. They contribute significantly to the conservation of biodiversity in the dry zone landscape.These migratory groups and the rural inhabitants have very good indigenous knowledge, and by following these methods, they not only increase long-term soil fertility and biodiversity, but also control plant diseases without harming the environment.

A large proportion of the scientific community has clearly stated that without inorganic fertilizer, our agricultural system will not be able to sustain itself, resulting in a severe food crisis and an increase in rural poverty. First, I support this collective observation as it is based on science. However, I started to explore further and compare what we see today and what I saw during my journeys sightseeing around the island in the 1960s. I remember observing an almost 6-inch-deep cow dung layer in villages around Sigiriya, Polonnaruwa, Anuradhapura, Batticaloa, Ampara, Panama, Moneragala, Hambantota and Madu areas. These were collected by Jaffna farmers by the truck load. People in those areas have the habit of digging pits and mixing cow dung with the soil. So, the whole landscape was pockmarked with these pits. This may be to break the hard-top layer to enable water to enter the ground so to collect seasonal rain. This prevents unused water from washing away the fertile soil and seeds. Finally, it allows seed germination and plant growth. Historically, large herds of cattle, buffalo, and goats roamed the entire country’s landscape, including pasture lands, shrub areas, and abandoned chena lands. These pastoralists have for centuries been in the habit of stocking pasture lands, shrub areas and abandoned chena lands with their herds. They contribute significantly to the conservation of biodiversity in the dry zone landscape.These migratory groups and the rural inhabitants have very good indigenous knowledge, and by following these methods, they not only increase long-term soil fertility and biodiversity, but also control plant diseases without harming the environment.

This practice ensures the safety and purity of water, and also makes use of available resources to produce food for people and animals. Here, I established that, with the green revolution of the 1960s which I witnessed and participated in, we destroyed our agricultural systems that had been practiced for thousands of years, and that I, too, was a big part of it, as were my colleagues in the scientific community. Today, these large herds of thousands of cattle, buffalo and goats are very rare and also restricted by the law. However, these domestic animal herds in these areas still outnumber the scattered wild animal concentrations within the forests in those areas. We should restock these lands by developing herding and land-use programmes, as well as developing an agroforestry network along the forest’s perimetre.This will allow the rural folks to coexist with the forest.

In the past, the adjoining forests to these marginal lands, too, used to play an important role in the life of the human population in rural Sri Lanka. Then the forest provided food, fuel, fiber and medicine. However, even till recent times the rural peasant has continued to coexist with the forests in harmony. Methodical hunting of old, sick or weak wildlife is vital to minimize the human-wildlife conflict, to prevent infections of domestic farm animals and passing on to the human population as in the case of Covid-19. Domestic cattle, buffalo and goat herds were mostly kept closer to forest boundaries in adjoining pasture lands, shrub areas and abandoned

chena lands.

As a result, the significance of these domestic animals as primary seed dispersers has been identified and documented. They consume herbage and seeds while grazing in one place, and excrete them in a different place. These seeds started growing in that place. In addition, this act of plant seed dispersal was reinforced by a secondary seed disperser known as the dung beetle who will then disperse some of the seeds to adjoining forest areas, thus increasing or maintaining biodiversity in forest areas. This was a synergic relationship during this period as it supported biodiversity within the forest areas. Evidence from plant demography research reveals that this form of seed dispersal might have an important role in determining patterns of tree diversity and distribution. Therefore, these farmers’ role in maintaining a diverse forest cover has to be identified and documented. However, this is not properly acknowledged.

After morning milking, almost all farmers send their cattle to free grazing on land designated as pasture land under the Pasturelands (Reservation and Development) Act 4 of 1983 (5441-19168-1-SM.pdf). The practice of allowing cattle to graze freely has been practiced for centuries. However, due to the legal pressures imposed by Circular 5/2001, this indigenous aspect of the free grazing system has been jeopardized. It resulted in a decrease in land availability in the total area for free grazing from 60-80% (1970-2000) to 5-30% (2001-2020) and created a seed dispersal limitation. The first observation following the implementation of Circular 5/2001 was that the ruminant population was deprived of adequate feed and nutrients to produce replacement stock and milk. The component of providing herbage through free grazing to these stocks was not included in the workload of the paddy and crop farming community. The second observation was a rapid decrease in the national ruminant numbers.

The Circular 5/2001, makes it practically impossible for smallholder farmers to rear farm animals. Hence, most had to discontinue a livelihood that sustained their crop cultivation activities by providing a daily income. Livestock supplemented their income on a daily basis as opposed to crop farming’s seasonal income. In addition, livestock has a significant asset value that can be used as collateral and in times of need. Therefore, livestock increases economic stability for rural peasants and smallholder farmers by serving as a cash buffer, a capital reserve, and a deterrent to inflation. Furthermore, it reduces risks associated with crop cultivation. Rearing livestock is not hassle free, but the outcome surpasses all that.

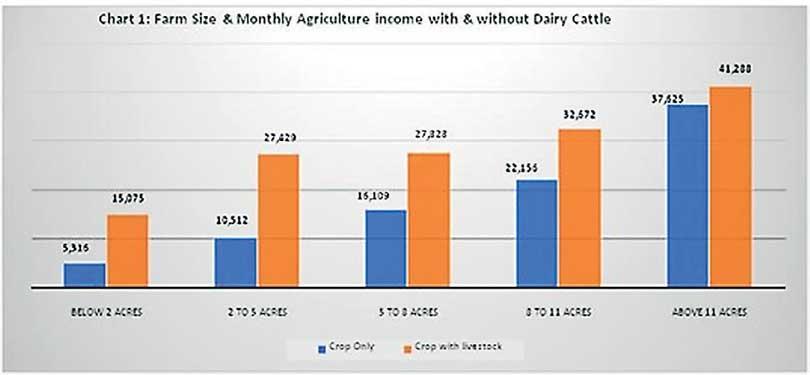

It is known that 82% rural peasants were part-time farmers (DA 2000) and was confirmed by a study in 2017. Furthermore, 80 % of smallholder farmers are blacklisted by formal lending organizations. According to a 2017 study, 75% of the remaining 20% not blacklisted are Crop-Dairy farmers. However, only 10.8% of farms have crop-dairy integrated operations. These smallholder farmers continued with their home garden crop-dairy integrated farming system. Others discontinued and found extra income generation outside farming. Chart 1 below depicts the monthly income disparities between different land holdings in Anuradhapura and Vavuniya (2017).

Farmers having below three hectares get almost twice the income from livestock than from crop farming. This group consists of around 90% of the farming community. Farmers above three hectares get twice the income as those below 3 hectares. This implies that the smallholders below 3 hectares should rear more cattle. This is only possible if the free grazing system can be used during the day and fed processed feed such as maize silage during the night time. The synergistic effect of Crop-Dairy integration, which enabled the vast majority of smallholder farmers to earn a decent living, was undone by Circular 5/2001.This has had a significant impact on the food production system, such as the increased use of inorganic inputs for crop cultivation. This is essential to compensate for the minimum time allocated to crop cultivation by these part-time farmers. This also resulted in narrowing the profit margins or turnover from crop product sales. Therefore, the bottom line is to increase the number of farmers doing integrated crop-dairy farming in all agro-ecological zones in Sri Lanka. However, this would give better results if this project mimicked the system that was practiced in ancient times.

All pasture land and marginal areas should be demarcated as ruminant grazing areas under the supervision of the relevant Veterinary Surgeon, the Agrarian Development Authority and the Forest Department. Only community grazing is allowed to be practiced. Pasture land areas in each village should be divided into sub-areas, enclosed and numbered. These three organizations should draw up a grazing schedule for each village. All cattle in a village should be allowed to graze in the number 1 sub-area, where the number of days depends on the availability of the feed resource base. Then a subsequent sub-area will be opened to graze all the cattle in that village. However, farmers should dig pits in the first sub-area and fill them with soil mixed with cattle manure. This rotation should continue year-round. All sub-areas should have access to water. Planting shade trees species selected by the Forest Department should be provided to the village farmer group. The responsibility of this tree growth is for cattle keepers using this facility. A programme has to be introduced to use culled cows for breeding to provide female calves for new farmers. Male cattle should be fattened before being sold to butchers in these areas.Culled cows should be maintained in these areas until death and the carcasses will be used for compost making. This project requires planning.

29 Nov 2024 7 minute ago

29 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

29 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

29 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

28 Nov 2024 28 Nov 2024