23 Nov 2024 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

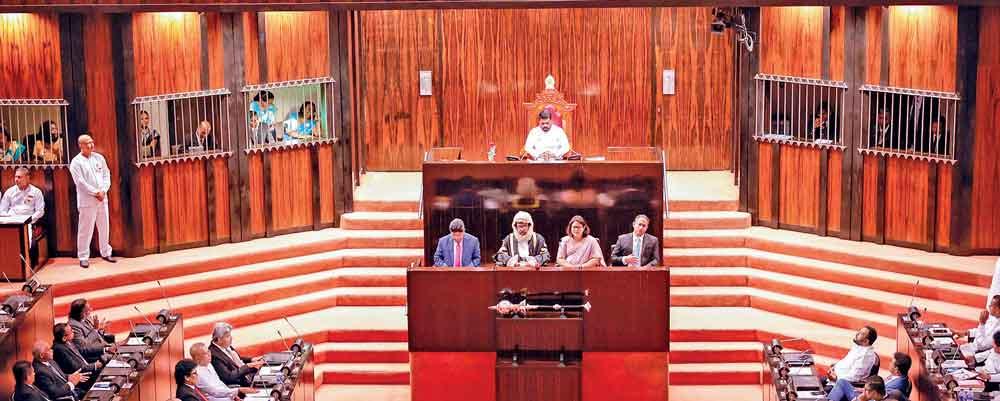

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake addressing the 10th Parliament

The NPP leadership’s ability to bring about reconciliation between Sri Lanka’s ethnic communities depends on relieving the economic pressures on ordinary people. If the new government fails, it would create room for xenophobic forces that would also feed into the already unstable global order.

The NPP leadership’s ability to bring about reconciliation between Sri Lanka’s ethnic communities depends on relieving the economic pressures on ordinary people. If the new government fails, it would create room for xenophobic forces that would also feed into the already unstable global order.

Sri Lanka has witnessed a major political shift in recent months. Anura Kumara Dissanayake of the National People’s Power (NPP) coalition won the presidential election held on September 21. It was the first time a candidate from neither of the two major parties that have ruled Sri Lanka since independence, or their offshoots, became president. Then, on November 14, the NPP won a landslide victory in parliament. It won over two-thirds of the seats, a number unprecedented under the system of proportional representation.

Consequently, the centre-left NPP government now has a tremendous mandate. Will it push back against the IMF austerity programme and provide relief to the people while rebuilding the economy in the aftermath of Sri Lanka’s worst economic crisis since independence? And can it find the political will for constitutional changes to abolish the authoritarian executive presidency and share power with minority communities?

The NPP draws its strength from the powerful uprising against President Gotabaya Rajapaksa in 2022 for his failure to address the economic crisis. Across the ethnic divide, people are focused on their livelihoods. This has opened the space to challenge the polarising but mutually dependent Sinhala Buddhist and Tamil nationalisms. Indeed, the most surprising outcome of the parliamentary elections was that for the first time a national party has won the electorates in the Tamil nationalist stronghold of the Northern Province.

The results represent a break with the past. The NPP’s chief constituent party, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), has a problematic history complicit with Sinhala nationalism. Its insurrection in the late 1980s opposed the Indo-Lanka Accord and devolution of power. It further joined a coalition with the government led by Mahinda Rajapaksa during the last phase of the civil war. These actions have raised concerns about the party’s position on minorities.

Since the end of the war in 2009, the JVP has embraced a range of democratic causes. However, it has stayed relatively silent on ethnic issues, gesturing towards national harmony rather than advancing power sharing with minorities. Nevertheless, with its victories in the recent elections, the NPP leadership has made it clear that it is increasingly open to engaging with minority communities, especially in the North, East, and Hill Country. That includes promising the release of lands occupied by the military in the war-torn regions. Given its own popularity in the South, it has the latitude to undertake these measures.

Unravelling global order0

In this context, the NPP’s ability to pursue efforts towards reconciliation are not solely determined by forces within Sri Lanka. The country is now buffeted by the crosscurrents of an unravelling global order. Many observers have tended to accuse Sri Lanka of creating its own problems. That included the successive failures of the majority leadership to address the concerns of minority communities. But today, the country’s exposure to external dangers reflects the growing weight of foreign over domestic politics in constraining or enabling democratic outcomes.

The NPP government is bound to face economic disruptions and geopolitical manoeuvres. It must prepare the country and take decisive action to manage the shocks. Trade volatility could undermine essential imports while global interest rate hikes may further aggravate Sri Lanka’s debt crisis.

In this context, how would regional powers at loggerheads, such as India and China, deal with a Sri Lankan foreign policy of neutrality? Sri Lanka was at the centre of the Non-Aligned Movement in the 1960s and 1970s. Unlike that moment, there appears to be little appetite for a similar coalition of countries in the Global South today. The NPP government will have to weigh the value of economic support from major powers and the political cost of aligning too closely with any of them.

Rethinking development

The determining factor is Sri Lanka’s development trajectory, including sources of development financing and its trade relationships. The new government should seek investments that align with a new development plan that can defend people’s living standards and rejuvenate livelihoods. Sri Lanka must be able to use international funding to make its own decisions about how to sustain its people.

That approach stands in stark contrast to the recent focus of funding mega infrastructure projects, which have been accompanied by speculation in luxury urban real estate. Moreover, Sri Lanka must build strategic complementarities through trade, rather than being told to liberalise its economy willy-nilly. The latter would only put further strain on the balance of payments.

Accordingly, a change in external engagement is urgently needed. India played a major role in providing Sri Lanka a lifeline during the Covid-19 pandemic and related economic woes. But India’s bridge financing came with the assertion that an IMF agreement was the only way out. The IMF programme and its ongoing austerity measures are going to be perhaps the biggest challenge for the new government. There is tremendous pressure from the West and India to stay the course.

The IMF path is bound to create a tremendous backlash given the social suffering. The NPP leadership’s ability to bring about reconciliation between Sri Lanka’s ethnic communities depends on relieving the economic pressures on ordinary people. If the new government fails, it would create room for xenophobic forces that would also feed into the already unstable global order. Consequently, the choice is clear. Dissanayake and his government should be given the space to act on the people’s mandate for change in Sri Lanka.

(Ahilan Kadirgamar is a political economist and senior lecturer, University of Jaffna. Devaka Gunawardena is a political economist and research fellow with the Social Scientists’ Association in Sri Lanka)

(Courtesy – The Indian Express)

21 Dec 2024 21 Dec 2024

21 Dec 2024 21 Dec 2024

21 Dec 2024 21 Dec 2024

21 Dec 2024 21 Dec 2024

21 Dec 2024 21 Dec 2024