29 Dec 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

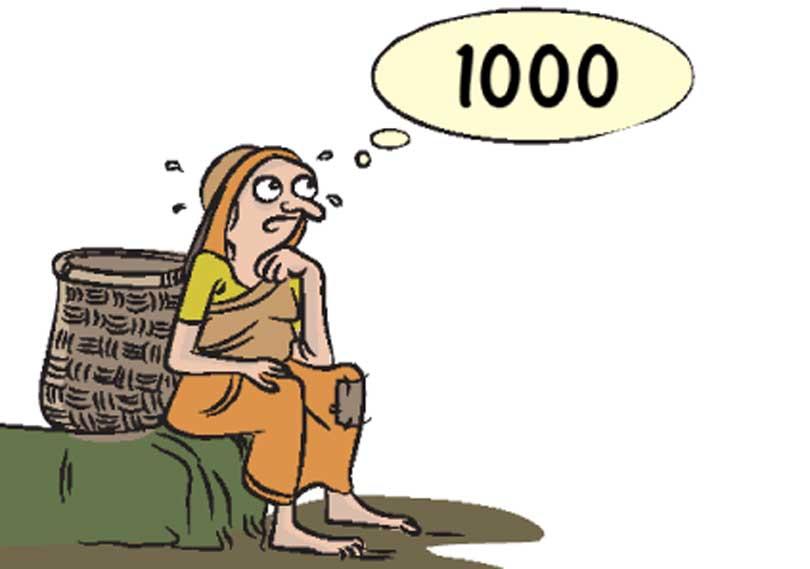

The Regional Plantation Companies, which manage Sri Lanka’s tea, rubber and coconut estates, are not budging on the estate workers salary issue, despite government leaders having repeatedly promised to increase their daily wage to Rs.1000. This was a promise given by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa during the presidential election campaign in November last year and the parliamentary election in August this year and by Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa in his 2021 budget speech on November 17.

In spite of the estate workers demand for the past three years that their daily wage be increased to Rs.1,000 and the recent promises by government and Opposition politicians to meet that demand, it is the regional plantation company management that has to decide on it. It is questionable as to why politicians give such a promise to the workers without reaching an agreement with the relevant companies. Hence, on the day after the Premier’s budget speech which included a proposal to increase estate workers’ salary to Rs.1,000, the Daily Mirror reported that the plantation companies had refused to comply. They had said that their views had not been obtained with regards to that budget proposal.

Politicians had the power to decide on matters concerning the plantation sector before the re-privatization of estates in 1992, because the sector was under two State entities, the Janatha Estate Development Board (JEDB) and the Sri Lanka State Plantation Corporation (SLSPC). Now that the estates are managed by private companies, the government is not in a position to decide on matters pertaining to the estates, except in case of reacquisition.

During the presidential election both the main candidates, Gotabaya Rajapaksa of Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) and Sajith Premadasa of the United National Party (UNP) in an irrational manner gave promises on this matter. Gotabaya Rajapaksa promised to meet the estate workers’ demand for a daily wage of Rs.1,000 under his presidency while Sajith Premadasa went further by promising to increase the estate workers’ daily wage to Rs.1,500, if elected to the presidency. One year has passed since Mr. Rajapaksa’s election to the top most post in the country, but the promise is still being repeatedly given to the gullible workers.

The fact that the government must first arrive at a decision on the matter with plantation managements does in no way mean that the workers do not deserve the salary they demand. They deserve it, by the recent claim by the plantation managements that they have evolved a new salary scheme under which workers can earn Rs.55,000 to Rs.70,000 a month, according to the above, the Daily Mirror news item said.

The plantation sector has been the main income earner for the country since the mid-nineteenth century until the Sri Lankan economy was diversified to some extent with the introduction of the open economy in 1978. In spite of the Rs.760 billion revenue earned by the garment industry and the Rs.950 billion remittances made by Sri Lankan migrant workers having surpassed the revenue earned by the plantation sector, before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the country; the latter still represents a major portion of the government’s revenue. The annual revenue earned by the tea, rubber and coconut plantations is around Rs.300 billion. The engine of this sector is no doubt the workforce, the plantation workers.

Yet, as a community, they live a pathetic life. Though there are individuals in the country who live a poorer life than that of average estate workers, the people living in plantation areas, with a large majority of them being people of Tamil-speaking Indian origin are the ones having the lowest living standards in the country, as a community. This is clear when comparing the national social indicators, such as literacy, life expectancy, maternal and child mortality with those of the estate sector. They are a community with lowest level of education and health facilities as well.

As a community, they are the ones who do not claim the ownership at least to one square inch of land on earth or to a house. A large majority of estate workers have been living for the past one and a half century in “line rooms”, an abode with a 10X10 feet room and an even smaller kitchen. The line room is their sitting room, bedroom and even storeroom, irrespective of the number and the marital status of the family members. This situation does not correspond with the accepted lifestyles of the 21st century. This is the story of the cup of tea we enjoy every morning. Hence, these workers should not be hoodwinked.

30 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 5 hours ago

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024