01 Jan 2021 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

‘The dignity of the dead, their cultural and religious traditions, and their families should be respected and protected throughout’, WHO guideline

‘The dignity of the dead, their cultural and religious traditions, and their families should be respected and protected throughout’, WHO guideline

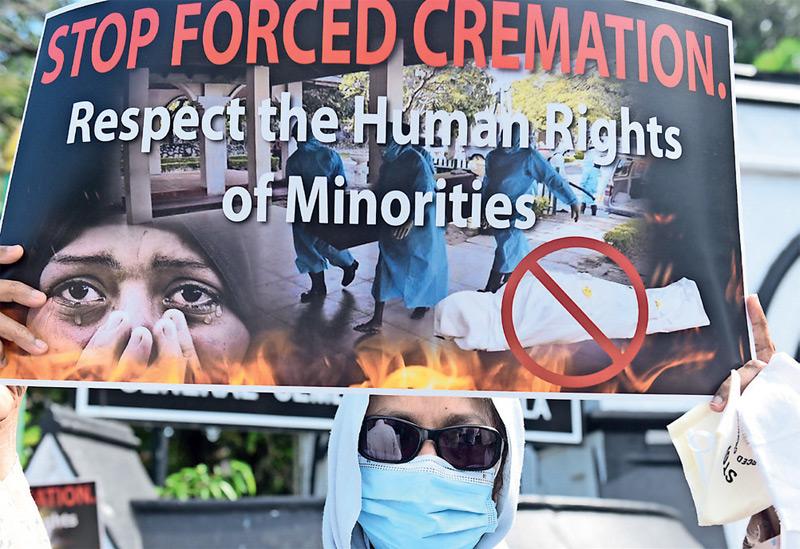

Forcible cremation has become the single greatest fear in the minds of Sri Lanka’s Muslims these days – more even than the pandemic itself. Irrespective of religious beliefs, assuring that a dead body (Janazah) receives a dignified burial is our shared culture and heritage. Whatever the religion, belief or ethnicity we belong to protecting the dignity of the dead is our utmost duty. Even though cremation of COVID-19 deceased affects many Christians as well, it is particularly devastating to Muslims, for whom the burial of the dead is a non-negotiable religious practice. The feeling that Muslims are being purposely targeted and wronged is gaining momentum within the community, particularly in view of a lack of any scientific reason to negate burial. The whole world is burying their COVID- 19 dead with no negative health effects and since the arrival of the novel coronavirus in December 2019, there is not a single reported instance of infection from buried corpses, even in the countries that conducted mass burials.

The Supreme Court’s refusal to grant leave to proceed to the fundamental rights petitions that were filed challenging cremation and to ensure that the last rites of COVID-19 dead are conducted according to each individual’s religious or personal beliefs that is enshrined in and protected by the Constitution has resulted in increased politicization of this issue. Some of us, who sought the intervention of court, are still recovering from the shock of hearing that the SC, by a majority decision, refused to grant leave to proceed to the 11 applications on December 1. Although the SC is entitled to give no reasons when refusing leave, as the final arbiter on citizens’ rights, especially when one of the judges had thought it fit to grant leave, it would have been salutary and served the public interest if the learned justices had at the least given reasons for the majority decision in such an important, sensitive and constitutionally protected rights matter. This we fear will have grave consequences beyond these cases and of the right of victims especially minorities and it once again shows that victims have limited remedies at the national level.

Racism doing politics with the dead is not new to us (the minorities) in this country. Denying the memorialisation of Tamils killed, bulldozing the martyrs’ cemeteries and crushing the mothers demand for justice to disappeared children – all deny closure to the families and dignity to the victims. The pain and distress of the family members as they are both hurt by the heartless action by the state, and the feeling of guilt, that they are failing to fulfil their duty to their deceased family members and their faith/religion, will gravely impact our collective healing and coming together as Sri Lankans anytime soon.

This act of cremation is being articulated by some politicians and some monks on the basis of the proposed ‘one country one law’, however, it is seen by the minority religious communities as the continuum of other discriminatory actions of the state and its agents in their repeated attacks on them. Hindu temples and shrines have been under attack by Buddhist monks and allied extremists claiming to protect ancient Buddhist heritage sites in the East while Evangelical and Anglican churches and pastors have also been under physical attack by such elements. The Muslim community has been the target of attacks from multiple fronts by monks and other citizens within a system that is subtly fuelling religious tension and hatred in the guise of protecting itself from Islamic extremists’ influence. The Extraordinary Gazette dated April 11, 2020 making cremation a must is part of that politics.

In the year 2021 one could only wish that the government will cease cremations and adopt the WHO guidelines on safe burial, joining more than 190 countries. This would mean that Sri Lanka would be adopting a science-based approach to control the spread of the virus so that the citizens can trust the government and feel safe to seek prompt medical attention when they have symptoms. The government should also acknowledge that Muslims by willing to forego three of the four rituals made compulsory in Islam in relation to burial: Washing, shrouding and praying, are agreeing to strictly follow all WHOs safe burial guidelines and accept government’s health procedures for burial. To date the National Hospital of Sri Lanka (NHSL) alone has ordered to cremate more than 100 COVID-19 causalities and half of them are Muslims. All the bodies, the NHSL stored in the freezer container that the health authority asked the Justice Minister to provide, are being cremated too. The health authority sought clearance from the Magistrate’s Court to cremate these bodies since their families have specifically stated in their police complaints that they do not want to give consent to their loved ones being cremated. Besides the religious reasons, one has to look at this protest as part of the family’s wish as well. The State cannot own dead bodies.

Families have left the bodies of their loved ones as a protest against forcible cremation and do not want to be part of a sin that the government is committing on the pretext of disease prevention. In Islam fire is connected to hell and punishment. One would understand the families’ pain and agony only when one speaks to them. It is not easy to leave dead bodies of one’s parents, grandparents, spouses, children or siblings because we Sri Lankans have a rich culture and tradition of respecting the dead and performing rituals collectively for the healing of bereaved families. So, first of all, it is wrong to label these bodies as unclaimed as some media reports and some health officials say.

Families have left the bodies of their loved ones as a protest against forcible cremation and do not want to be part of a sin that the government is committing on the pretext of disease prevention. In Islam fire is connected to hell and punishment. One would understand the families’ pain and agony only when one speaks to them. It is not easy to leave dead bodies of one’s parents, grandparents, spouses, children or siblings because we Sri Lankans have a rich culture and tradition of respecting the dead and performing rituals collectively for the healing of bereaved families. So, first of all, it is wrong to label these bodies as unclaimed as some media reports and some health officials say.

30 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

30 Nov 2024 5 hours ago

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024

29 Nov 2024 29 Nov 2024