16 Jun 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It is encouraging to see that despite being severely cash-strapped due to the absence of an independent allocation in the 2017 National Budget, the RTI Commission of Sri Lanka has begun hearing appeals and concluded several hearings under the globally acclaimed RTI Act No:12 of 2016.

This is no doubt due to the perseverance of Commission members despite the Commission operating out of temporary premises and with skeletal staff.

It was reported that the appellants were recording their appreciation of the fact that this was a law which gave ‘ordinary people’ the right to ask questions from the establishment. This included even public servants who have no recourse to questioning the establishment when they themselves became the victims of injustice. Parents of children who had been denied admission to schools without giving reasons and journalists attempting to expose corruption in the Provincial Council machinery have stated that they have gone before the Commission.

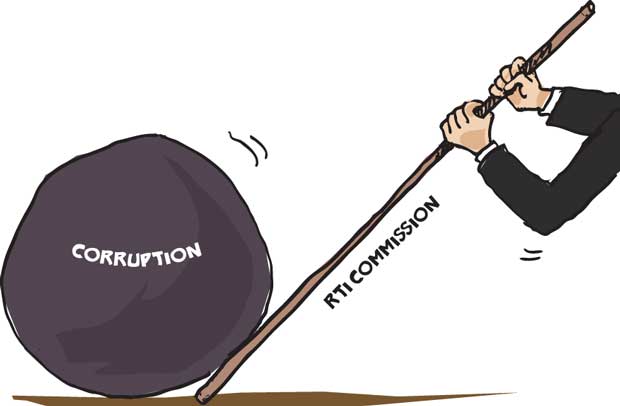

No doubt, all this is an important part of the RTI regime. RTI is a weapon that acts as a leveler against privilege. Whether it is the politically, socially or financially privileged makes no difference. Any citizen can file an RTI request and cannot be questioned as to why it is being filed. If it falls within the reach of the RTI Act, it will be granted. If not, then those refusing must explain why and will be held responsible before the Commission.

However citizens including journalists who file appeals to the Commission must be aware of the legal processes even though they have been relaxed to a great extent. The RTI Act and the Regulations allow initial information requests to be filed electronically (through email). But appeals to the Commission must be by registered post or person. To our mind, this safeguard must be to prevent fraud at the appeal stage. This is necessary.

The Commission sits on appeal against a decision of a Designated Officer (DO) in a Public Authority in response to a rejection of an information request by an Information Officer. A citizen cannot simply ignore an appointed DO and come directly to the Commission saying that it is ‘of no use’ to appeal. The steps laid down in the law must be followed. An appeal will lie directly to the Commission only when a DO is not in place, as we understand it.

The Commission has announced in a recent media statement that it is pleased with the public’s use of RTI. Considerable numbers of citizens and public officers have reached out to the Commission in these early months. Its Draft Rules on the duties of Ministers to publish certain categories of pro-active information in advance will soon be available for public feedback on its eagerly awaited website.

It is a special feature of our RTI Act that Ministers are required to publish information regarding future projects above a particular monetary value, including information on procurement and tender processes. These are areas where the most corruption has been evidenced. In addition and under other provisions of the Act, Ministers are also required to publish disbursements under allocated budgets. This would involve, among others, costs incurred for junkets abroad.

In a further development, regulations are pending before Parliament to enable public access to the declarations of assets and liabilities of parliamentarians who are elected to office and are thus directly covered by RTI. This is a praiseworthy development and would, no doubt, further strengthen the steadily growing RTI regime in Sri Lanka.

What we see taking place today is a quiet and gradual change in the culture of not asking questions which Sri Lankans have been used to for decades. Despite all the criticisms levelled against this Government, it is to its credit that it brought RTI to the citizens. Its benefits will come in the years ahead if the RTI process is supported and encouraged rather than sabotaged.

30 Oct 2024 36 minute ago

30 Oct 2024 42 minute ago

30 Oct 2024 47 minute ago

30 Oct 2024 2 hours ago

30 Oct 2024 2 hours ago