13 Sep 2016 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

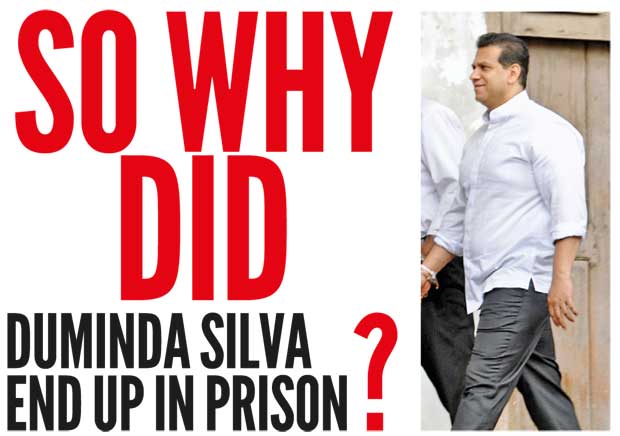

t is rather strange that nobody has yet cried ‘conspiracy’ over the High Court sentencing Duminda Silva and four others to death last week on charges of murdering Bharatha Lakshman Premachandra and three others. Perhaps that indifference, even of his fellow travellers in the former regime, is understandable. Judging by the public reactions to the court verdict, Silva is deeply unloved. But, that is a bit confusing though; here was a man who polled the highest number of preferential votes at two consecutive provincial elections -- in the second, he obtained a whopping on 165,000 votes, and then went to win a seat in parliament obtaining 146,000 votes at the 2010 general elections. He could

t is rather strange that nobody has yet cried ‘conspiracy’ over the High Court sentencing Duminda Silva and four others to death last week on charges of murdering Bharatha Lakshman Premachandra and three others. Perhaps that indifference, even of his fellow travellers in the former regime, is understandable. Judging by the public reactions to the court verdict, Silva is deeply unloved. But, that is a bit confusing though; here was a man who polled the highest number of preferential votes at two consecutive provincial elections -- in the second, he obtained a whopping on 165,000 votes, and then went to win a seat in parliament obtaining 146,000 votes at the 2010 general elections. He could  well have won this time had not President Maithripala Sirisena refused him nomination even after his name appeared in the nomination list. Going by the calibre of most individuals who made it to Parliament from the UPFA in last year’s election, Mr Silva’s chances were a near certainty. Had that happened, he could well have another rather insalubrious accolade to his name: The first sitting parliamentarian to be sentenced to death. His counsel say he and others would appeal.

well have won this time had not President Maithripala Sirisena refused him nomination even after his name appeared in the nomination list. Going by the calibre of most individuals who made it to Parliament from the UPFA in last year’s election, Mr Silva’s chances were a near certainty. Had that happened, he could well have another rather insalubrious accolade to his name: The first sitting parliamentarian to be sentenced to death. His counsel say he and others would appeal.

However, he did not have to take that time-consuming and exhausting process, had the fortunes of the former regime prevailed. It could have been one phone call to the judges and all would have  walked out free. It is alleged that it was simply to evade justice that Mr Silva pole-vaulted to the UPFA from the UNP from which he was first elected to the Western Provincial Councillor in 2004. While serving as a provincial councillor, he was implicated in rape. UNP leader Ranil Wickremesinghe sacked Mr Silva from the party. He joined the UPFA and his fortunes changed; the Attorney General threw away the case against Silva purportedly on procedural grounds. He won the provincial council election in 2009, polling the highest number of preferential votes in the Colombo District and then contested and won at the general election in 2010. He became a trusted lieutenant of the powerful defence secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa, and was appointed a monitoring MP for the Defence Ministry. Thus he became a patriot, the most bankable trait under the former regime -- notwithstanding the rumours of his alleged involvement in the heroin trade. (Welle Suda, the drug kingpin repatriated from Pakistan has confided to the CID that he gave Mr Silva one million rupees on the latter’s demand. Silva was questioned on that by the police)

walked out free. It is alleged that it was simply to evade justice that Mr Silva pole-vaulted to the UPFA from the UNP from which he was first elected to the Western Provincial Councillor in 2004. While serving as a provincial councillor, he was implicated in rape. UNP leader Ranil Wickremesinghe sacked Mr Silva from the party. He joined the UPFA and his fortunes changed; the Attorney General threw away the case against Silva purportedly on procedural grounds. He won the provincial council election in 2009, polling the highest number of preferential votes in the Colombo District and then contested and won at the general election in 2010. He became a trusted lieutenant of the powerful defence secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa, and was appointed a monitoring MP for the Defence Ministry. Thus he became a patriot, the most bankable trait under the former regime -- notwithstanding the rumours of his alleged involvement in the heroin trade. (Welle Suda, the drug kingpin repatriated from Pakistan has confided to the CID that he gave Mr Silva one million rupees on the latter’s demand. Silva was questioned on that by the police)

Lately Mr Silva became a pillar of ex-president Mahinda Rajapaksa’s youth brigade, i.e. a bunch of servile young MPs the ex-president groomed to buttress his dynastic ambitions. Many of them were more or less a bunch of hooligans straight out of gang-lands, they shouted down the opposition MPs in Parliament and terrorized opposition supporters in their electorates. They enthusiastically placed their signatures on a blank paper, which later became the no confidence motion against the former chief justice. Nonetheless, they oozed patriotism; thuggery, murder, trade in party pills and heroin,  extortion and all other evil appeared petty distractions set against their patriotic persona. Even by those standards, Mr Silva was the envy of the coterie; from a rape accused, he became the monitoring MP of the powerful defence ministry. That was no mean feat.

extortion and all other evil appeared petty distractions set against their patriotic persona. Even by those standards, Mr Silva was the envy of the coterie; from a rape accused, he became the monitoring MP of the powerful defence ministry. That was no mean feat.

Politics and electioneering, in particular, in this country are associated with thuggery. However, those like Mr Silva (and also his alleged victim Bharatha Lakshman, no saint! ) gave it a populist appeal, reaching out to the slums and picking up the worst of the things to form the most formidable politically connected underworld gangs. Thus the political power gradually shifted from the law- abiding decent people to the thugs and the slums. On one fateful day during the run up to the local government elections in October 2011, two such gangs canvassing for rival candidates met in Kotikawatta and in the ensuing gun fight, rival party stalwart Baratha Lakshman and three others were murdered. Silva himself was shot but survived. Five years later, now with his government out of power, the court last week sentenced Silva and three of his bodyguards to death. The fifth suspect who had been absconding is feared to have been ‘white-vanned’ when the former regime turned on some members of the underworld.

Silva (and his bodyguards) are both perpetrators and victims of the permissive culture of violence and thuggery his patrons of the former regime fostered. They were shielded from the long arm of the law by the regime leaders, whose dispensing of justice was selective and arbitrary. The court had little say in those matters then. Dysfunctional courts and the non-existent rule of law skewed the cost-benefit ratio of thuggery. When the deterrent was removed, Silva and others found no reason for restraint. If the rape charges could be thrown away by virtue of being a ruling party MP, why not murder charges, they might have thought.

Now that the tables have turned -- and assuming that the judiciary has regained independence -- it is payback time. However, it is not only Silva who is being haunted by the past deeds. An already lengthy list is getting lengthier: Basil and Gotabaya are indicted for financial crimes and corruption, Namal and Yoshitha are also charged. A host of ministers, parliamentarians and officials affiliated with the former regime are making regular appearances before the FCID. It may be tempting to label those investigations as witch-hunts, but most of those allegations stem from the former regime’s sheer contempt to the rule of law and barefaced impunity. Former president Mahinda Rajapaksa discarded those basic tenets of a democratic and accountable government in pursuit of his personal and political ambitions. Even he could not have expected that infractions he initially turned a blind eye to would grow into mammoth proportions they later reached. However, once thuggery, impunity and officially sanctioned violence were allowed, they took a life of their own and were self-perpetuated. The former chairman of the Tangalla Pradeshiya Sabha, a goon of the ex-president, killed a British tourist and raped his girlfriend. Mr Rajapaksa did not see it coming. Nor did he even in his wildest dream expect Duminda Silva et al. would murder his onetime buddy BarathaLakshman. However, the culture of impunity and glorified thuggery he permitted let that happen. Mr Rajapaksa is not the only political leader who institutionalized a culture of thuggery.(Much is written about first executive president J.R. Jayawardene’s culpability.) However it is sad that the evil that was made possible by Mr Rajapaksa’s carte blanche for thuggery and arbitrariness now threatens to undo his legacy, which albeit its sordidness, has some unparalleled triumphs.

25 Dec 2024 3 hours ago

25 Dec 2024 3 hours ago

25 Dec 2024 3 hours ago