15 Oct 2024 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The National List in Sri Lanka's parliamentary system was originally designed to enhance inclusivity and ensure that marginalized voices are represented in governance. This provision allows political parties to nominate candidates to Parliament who have not contested in the general elections, thereby providing a mechanism for underrepresented groups to gain access to legislative power. However, the noble intent behind this system has increasingly been overshadowed by manipulation and abuse, as political parties exploit the National List for patronage, sidelining public accountability and transparency.

The National List in Sri Lanka's parliamentary system was originally designed to enhance inclusivity and ensure that marginalized voices are represented in governance. This provision allows political parties to nominate candidates to Parliament who have not contested in the general elections, thereby providing a mechanism for underrepresented groups to gain access to legislative power. However, the noble intent behind this system has increasingly been overshadowed by manipulation and abuse, as political parties exploit the National List for patronage, sidelining public accountability and transparency.

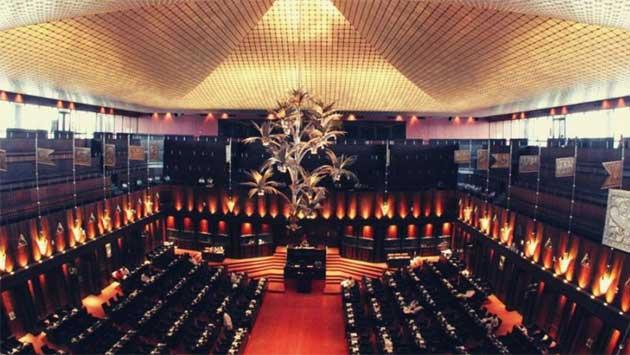

The National List was introduced as part of Sri Lanka's electoral framework with the aim of ensuring diverse representation in Parliament. Each political party can submit a list of candidates, which is then allocated seats in proportion to the party's overall vote share. Currently, there are 29 national list MPs alongside 196 elected MPs, resulting in a total of 225 members in Parliament. The mechanism was intended to allow for the representation of minority communities, professionals, and other sectors of society that may not receive adequate representation through direct electoral competition.

The idea of a national list of MPs emerged from the establishment of the Senate and the House of Representatives in Ceylon under the Soulbury Commission in the 1940s. Initially, the House included six members appointed by the Governor-General, on the Prime Minister's advice, to represent interests that were not adequately represented, primarily from the European and Burgher communities, and occasionally from Indian Tamils and Muslims. Over time, the system evolved, but the underlying intent remained the same to ensure that the legislature reflects the diverse makeup of Sri Lankan society.

The Intended Purpose

The primary goal of the National List is to facilitate the inclusion of underrepresented groups, ensuring a more diverse and equitable legislative body. By allowing parties to nominate individuals with specialized knowledge or skills, the National List aims to enhance parliamentary debates and policymaking, thus providing a counterbalance to traditional electoral outcomes that may not fully represent the spectrum of societal interests.

Moreover, the National List is seen as a means to bring in experts from various fields, such as healthcare, education, and social services, who can contribute to informed policy decisions. In this sense, the list was meant to serve as a bridge between the electorate and the intricacies of governance, allowing for the infusion of expertise into legislative processes.

The Misuse of the National List

Despite its intended purpose, the National List has become a focal point for political maneuvering and abuse. Political parties often nominate individuals who lack grassroots support or the ability to win in a competitive electoral environment. This allows parties to appoint loyalists or insiders who may not have any legitimate public mandate. As a result, these appointed individuals are frequently disconnected from the constituents they are supposed to represent, leading to a lack of accountability and engagement with the electorate.

A pervasive culture of patronage has emerged, wherein the National List is used to reward loyal supporters, campaign financiers, or influential party members. This trend diminishes the overall quality of representation in Parliament, as political loyalty often takes precedence over public service or expertise.

A notable example occurred during the 2022 political crisis, when national list MP Ranil Wickremesinghe was appointed prime minister and later succeeded as President after Gotabaya Rajapaksa fled the country. This situation raised serious questions about the democratic principles underlying the appointment process.

Currently, national list nominations are often seen as tools for inducement and appeasement, used at the discretion of party leaders. For instance, both Mervyn Silva (2004, UPFA National List) and Wickremesinghe (2021, UNP National List) were defeated candidates in general elections but received nominations through their respective parties. Wickremesinghe's rise to the presidency further highlights concerns about the integrity of the electoral process.

As the general elections scheduled for 14 November 2024 approach, the ruling National People’s Power (NPP) is positioned to capitalize on the momentum gained from the recent presidential election held on 21 September. Under Article 99A of the Constitution, all political parties and independent groups contesting the elections are required to submit lists of national list nominees during the nomination period.

The NPP has unveiled its list of candidates nominated as national list MPs for the upcoming election. Notably, for the first time in Sri Lankan history, the NPP has included a candidate representing the differently-abled community. This move reflects an attempt to broaden the scope of representation and incorporates a diverse array of professionals, including businessmen, lawyers, doctors, engineers, and civil activists.

In contrast, other parties, such as Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB), the New Democratic Front and Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna, have released their national lists, which prominently feature former MPs and party loyalists. Critics argue that this approach undermines the very purpose of the National List, as it often excludes individuals with specialized skills or knowledge who could significantly contribute to the legislative process.

For the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB), it looks like many of the senior figures will make their way into Parliament through the national list. This includes well-known names like Ranjith Madduma Bandara, Imthiaz Bakeer Markar, Dullas Alahapperuma, G. L. Peiris, and Rohana Lakshman Piyadasa. While these individuals have a wealth of experience, the public is questioning whether the party is offering enough new talent or simply relying on familiar names to maintain its footing.

The New Democratic Front has also been facing criticism, with many people expressing disappointment over its national list. While some familiar faces from past governments appear, like former Prime Minister Dinesh Gunawardena and former Speaker Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena, the list is also populated by former ministers like Faiszer Musthapha, Tiran Alles, Ravi Karunanayake, and Thalatha Athukorale. This has led many to feel that the party is missing an opportunity to bring in fresh voices and professionals, instead of recycling the same old political players.

As for the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP), its national list features several senior former ministers, including Gamini Lokuge, C.B. Ratnayake, and Thissa Vitharana. While they bring experience to the table, the inclusion of former MP Thissa Kutti Arachchi and actress Anusha Damayanthi has raised eyebrows. Some view this as a way to appeal to a broader audience, while others feel it’s more of the same political names and celebrity endorsements instead of new, dynamic leadership.

The SLPP, which had a strong majority in the previous parliament, has also experienced setbacks recently. Several members defected after the presidential election, leaving the party to join the SJB or NDF, which has only added to the perception that the ruling party is in a state of flux.

Overall, there’s a sense of disappointment from many voters. While these national lists include some big names and experienced politicians, there’s a growing feeling that they don’t represent the fresh ideas and professional expertise that people are hoping for. In a time of uncertainty and economic struggle, many are asking if the same old faces are really what the country needs right now.

The Impact of Public Trust

The Commissioner General of Elections has made it clear that these lists must accurately reflect Sri Lanka’s demographics and ensure adequate representation of women. Only those listed as nominees can enter Parliament, and all national list nominees are required to submit declarations of assets and liabilities in accordance with new anti-corruption laws. This regulatory framework aims to enhance transparency and accountability within the electoral process.

Despite these measures, public trust in the National List is eroding. Nearly thirty former MPs from the previous parliament have opted not to contest in the upcoming general elections, citing various reasons, including fear of public backlash due to widespread dissatisfaction with their past performance. Many of these politicians are now seeking entry into Parliament through the National List, effectively bypassing direct elections. This trend raises concerns about the legitimacy of their appointments and whether they genuinely represent the will of the electorate.

Even Namal Rajapaksa, the presidential candidate for the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna, has opted for this route, illustrating a strategic shift among politicians wary of direct competition.

As some parties continue to nominate former MPs to the National List, tensions are emerging within political factions. Critics contend that this practice often prioritizes party loyalty over merit, resulting in the exclusion of individuals with specialized knowledge who could contribute meaningfully to governance. Many party members express concerns that qualified professionals—experts in fields such as healthcare, education, and environmental science—should be included in the National List to enhance the overall competence and diversity of parliamentary representation.

The Need for Electoral Reform

The misuse of the National List has far-reaching implications, undermining public confidence in the political system. When citizens perceive appointments made without regard for public opinion, it breeds cynicism toward elected officials and the democratic process itself. This disconnect can lead to voter apathy and disengagement, posing a significant threat to the health of democracy in Sri Lanka.

In light of these growing concerns, there is an increasing call for electoral reform. Civil society groups and advocates are urging stricter regulations on National List nominations to ensure that they genuinely reflect societal needs and provide meaningful representation. This push for reform underscores a collective desire for a more accountable and responsive political system that can effectively address the diverse interests of the Sri Lankan populace.

The National List was intended to enhance representation and inclusivity within Sri Lanka's parliamentary framework. However, its current misuse reveals significant flaws in the political system, allowing parties and ineffective politicians to evade accountability and public scrutiny. To restore faith in the democratic process, reforms are needed to realign the National List with its original objectives, ensuring it serves the interests of all citizens and improves the quality of governance in Sri Lanka.

24 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

24 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

24 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

23 Nov 2024 23 Nov 2024

23 Nov 2024 23 Nov 2024