23 Sep 2022 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

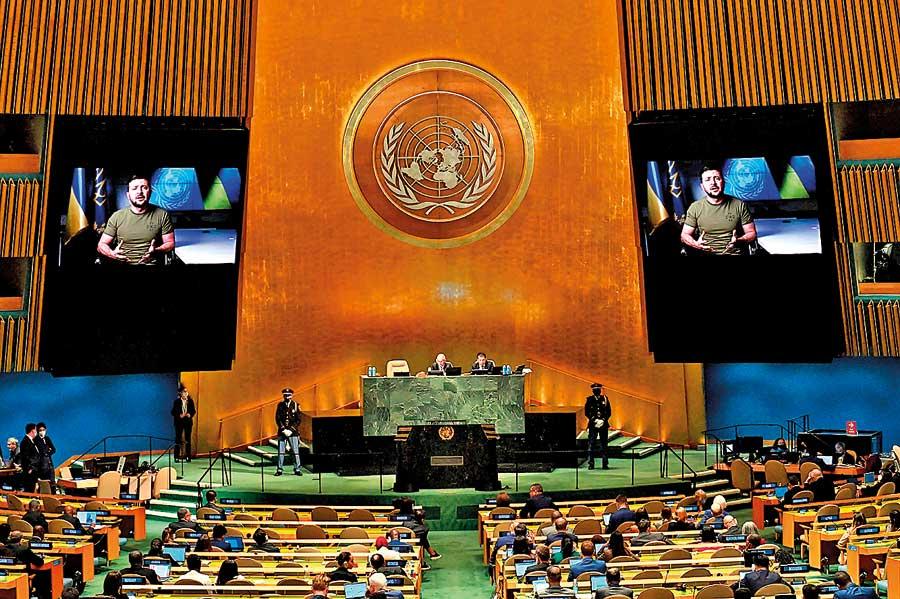

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky is seen on screen as he remotely addresses the 77th session of the United Nations General Assembly at the UN headquarters in New York City on Wednesday. AFP

Often derided as a talk shop by its detractors, the United Nations is in session for the annual General Assembly summit. Although this year’s summit is seen as the first biggest gathering of world leaders in person after a three-year pandemic-hit gap, there is little to celebrate. Certainly, it won’t be a game changer.

summit. Although this year’s summit is seen as the first biggest gathering of world leaders in person after a three-year pandemic-hit gap, there is little to celebrate. Certainly, it won’t be a game changer.

The annual UN summit is like a firework display. It is colourful and attractive. It briefly lights up the dark sky, stirring the hope of those groping in the dark. Then it is not there.

As a result, decades-old conflicts still elude solutions, though, at the summit of the 193-member global body, they are spoken of, together with new conflicts. World peace appears to be the least of the priorities of the member-states whose primary objective is to enhance their national-interest objectives through UN forums.

Since its inception in 1945, the UN has been beset by big power rivalries while hundreds of conflicts raged in all corners of the world. One of the first major challenges the UN faced was the Palestinian crisis. The Western powers which were dominating the world body then, just as they are doing now, instead of making use of the good offices of the UN to achieve peace, worked towards an unjust UN resolution. In a preposterous division, Palestine was divided to create Israel, giving 55 percent of the land to the 30 percent Jewish population and 45 percent of the land to the 70 percent Palestinian population.

Most of today’s UN members were not a party to the Charter that was signed on June 26, 1945. Only 51 countries, regarded as founding members, negotiated the charter and allowed the formation of a gang of five comprising the powerful UN Security Council members with veto powers, which were, as studies show, often used to promote war or prevent peace. States that obtained membership later had to swallow the undemocratic charter whether they like it or not.

Since the founding members are now heavily outnumbered by those who joined later, it is high time some serious dialogue was held to reform the world body, which is handicapped by system errors, as a result of which the UN is unable to eliminate global injustice and end conflicts.

The main defect is in the structure itself. It has been structured to serve the interest of the big powers rather than achieving the noble goals spelt out in the UN charter. In the preamble, the charter says the UN was set up “to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war…” It goes on to emphasise respect for international law.

Yet the rule-based international order the charter envisages is often violated by the very big powers that put those highfalutin words into the preamble.

In 1994, John Bolton, who later became Washington’s UN envoy during the Donald Trump presidency, said that if the UN Secretariat building in New York “lost 10 stories, it wouldn’t make a bit of difference.” Although neocon Bolton’s criticism was rooted in his disdain for the global body, the track record shows that the UN was a one-big scandal wrapped in false hopes that it can intervene and make peace between warring nations and it can penalise the aggressor. Ask the oppressed people in Palestine, Kashmir, Syria, Rwanda, and other trouble spots of the world, they will say the UN has failed to protect them. Even in Sri Lanka, during the last stages of the war, the UN suddenly ended its presence in the war zone, shirking its responsibility to protect the tens of thousands of people who pleaded with UN officials not to abandon them. In Rwanda and Srebrenica in the 1990s, the UN was helpless to prevent genocide despite its presence. The UN could do virtually nothing when in 2003 the US invaded Iraq by unilaterally misinterpreting the UN resolutions.

And now the US rues the day when Russia is doing to Ukraine what the US did to Iraq.

With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine dominating the current UNGA summit, the talk of UN reforms is being heard louder than ever in the US, traditionally a reform resister. This is because the Joe Biden administration is frustrated by its inability to hold Russia accountable for its invasion of Ukraine due to Moscow’s veto power in the Security Council.

Reform-minded Third World leaders have said that instead of the Security Council, the General Assembly should be the decision-making body of the UN. Libya’s slain leader Muammar Gaddafi, who was well respected in the Third World for his campaign against western neocolonialism, once said: “Why are we asking for democracy in countries, when there is a dictatorship in the U.N. (and) if we can’t establish democracy in the world parliament.”

Just as Gaddafi wanted, most countries are now inclined to strengthen the UNGA where no country wields veto power. Recently, the US and its Western allies succeeded in passing a binding UNGA resolution evicting Russia from the UN Human Rights Council.

However, there is no indication that the US, despite its reform push, is keen on abolishing the veto system. It is for expanding the Security Council. According to an AFP report, Washington’s UN envoy Linda Thomas-Greenfield has voiced her country’s support for “sensible and credible proposals” to expand membership in the 15-nation Security Council.

She said that the veto-wielding Permanent Five -- Britain, China, France, Russia, and the United States -- had a special responsibility to uphold standards and promised the US would exercise its veto only in “rare, extraordinary situations.”

“Any permanent member that exercises the veto to defend its own acts of aggression loses moral authority and should be held accountable,” she said, in a clear reference to Russia.

Her statement, however, is scoffed by analysts who point out that over the past five decades, the US has vetoed at least 53 UN Security Council resolutions critical of Israel.

Time and again there emerges consensus to expand the Security Council by incorporating more permanent members, especially Brazil, Germany, India, Japan, and other countries which have a bigger say in international politics, but geopolitics have put paid to hopes of such reforms.

Like the US, both China and Russia have no intention to give up their veto powers, because China needs veto power to quash Security Council action in case it resorts to military action to reunite with Taiwan and Russia needs it to ward off further punitive measures against it in the Security Council in view of its Ukraine invasion.

The Security Council has a key role to play, but there should be more checks and balances to prevent the abuse of veto power. For instance, a veto should be nullified if ten members – or two-thirds of the council -- vote for a resolution. But are there any takers for such sweeping reforms?

10 Jan 2025 12 minute ago

10 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 4 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 4 hours ago